Penn exhibition surfaces the story of Minerva Parker Nichols, the first American woman to have an independent architecture practice

Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect

University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design

Harvey & Irwin Kroiz Gallery of the Architectural Archives

220 South 34th Street

Philadelphia

Through June 17

It would be easy to miss the entrance to the Architectural Archives on the lower level of the Fisher Fine Arts Library Building at the University of Pennsylvania’s Weitzman School of Design. Looking out onto a set of stair-stepped seating, a stone bearing a time-worn carving next to an unassuming single door denotes the building’s purpose. Through that door, a ceiling-height wall painted blueprint-blue greets visitors with a name in all caps: Minerva Parker Nichols. After ringing the bell next to a second door, opening it, and going down a few steps, visitors will find themselves in an archive with tables for researchers and dozens of file boxes. Amid these historical artifacts and ongoing research, an exhibit about Nichols, the first American woman to have an independent architecture practice, begins.

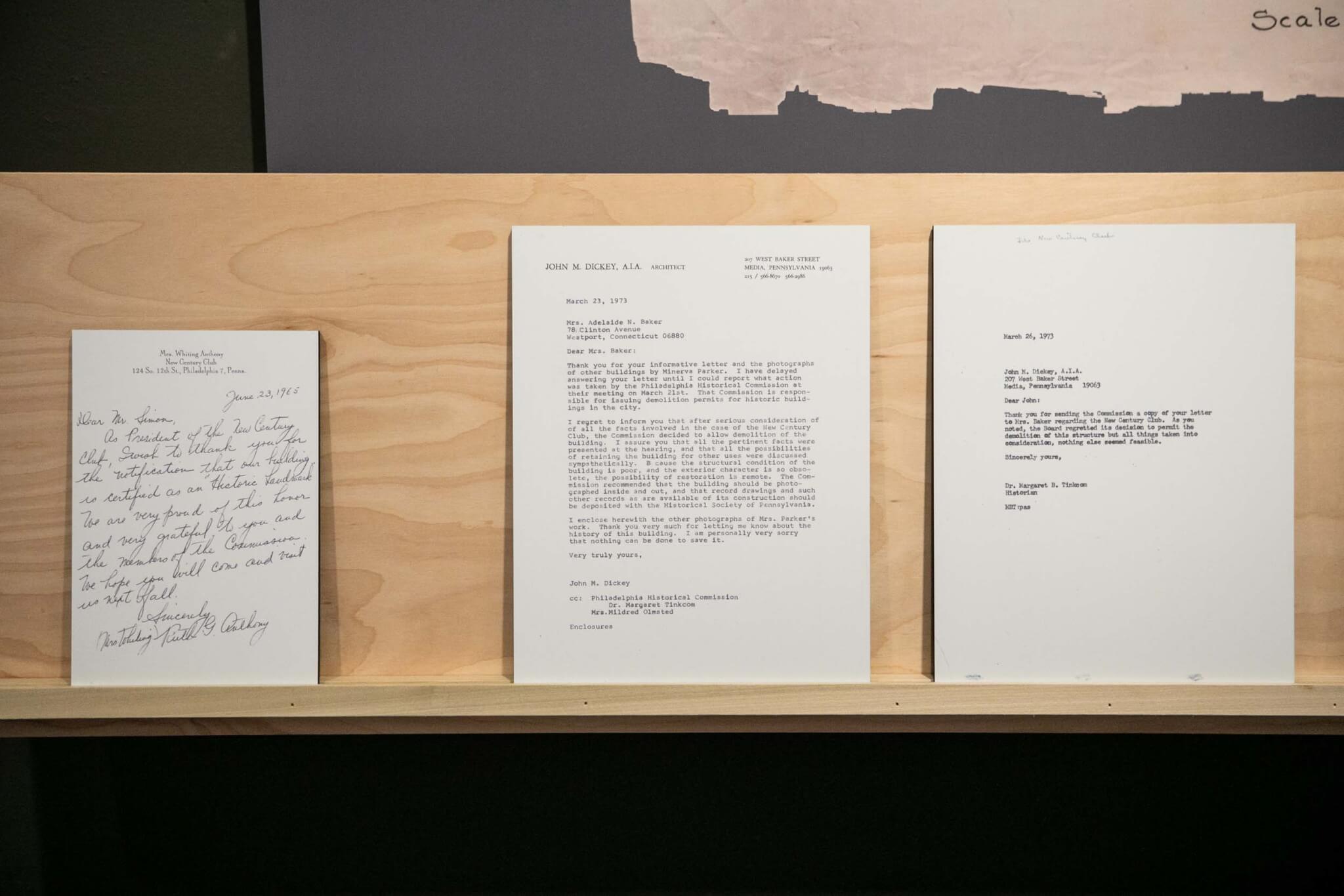

Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect starts with a story told through letters: In 1973, the New Century Club of Philadelphia, a landmarked building designed by Nichols in 1891, was set to be demolished due to disrepair. Despite protests from Nichols’s daughter Adelaide Baker, the decision had been made. As evidenced by the correspondence on display, John M. Dickey of the AIA and Margaret Tinkcom of the Philadelphia Historical Commission agreed that the building had to come down, and it did.

Of the half dozen non-residential buildings Nichols designed over her decade-long formal career (she kept designing even after formally retiring), only one still stands: the New Century Club of Wilmington. Opening the show with the story of a demolition seems to be a cautionary gesture, urging viewers to learn this history so that they might prevent such an erasure from happening again.

This kind of didacticism makes sense given the respective areas of expertise of the show’s organizers. William Whitaker, who led its curatorial team, has been the curator and collections manager of the Architectural Archives since 1998. Lead scholar and cocurator Molly Lester, an architectural historian and preservation planner, has been researching Nichols for a decade; she has published several journal articles related to Nichols and produced a podcast called What Minerva Built. The team is rounded out by Heather Isbell Schumacher, archivist of the Architectural Archives, and Elizabeth Felicella, a documentary photographer specializing in in-depth architectural documentation. Given this line-up, historical lessons, however subtle, were bound to abound.

The show continues from the archive’s main room into a pair of spaces connected by a winding ramp. Here, the exhibit traces Nichols’s career chronologically, starting with her 1862 birth in Illinois, her family’s relocation to Philadelphia in 1876, her enrollment in the Philadelphia Normal Art School in 1879, and her apprenticeship under Edwin W. Thorne, a residential architect, in the 1880s. This last experience, along with her enrollment in the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Arts from 1888 to 1889 to pursue a drawing certificate, established the character of her career as an architect of primarily residential buildings. In 1888, after Thorne moved his practice from Broad Street to Arch Street, Nichols—then still Parker; the show circumvents potential confusion around the name change by referring to her as “Minerva” throughout—took over his former office space and began her independent practice.

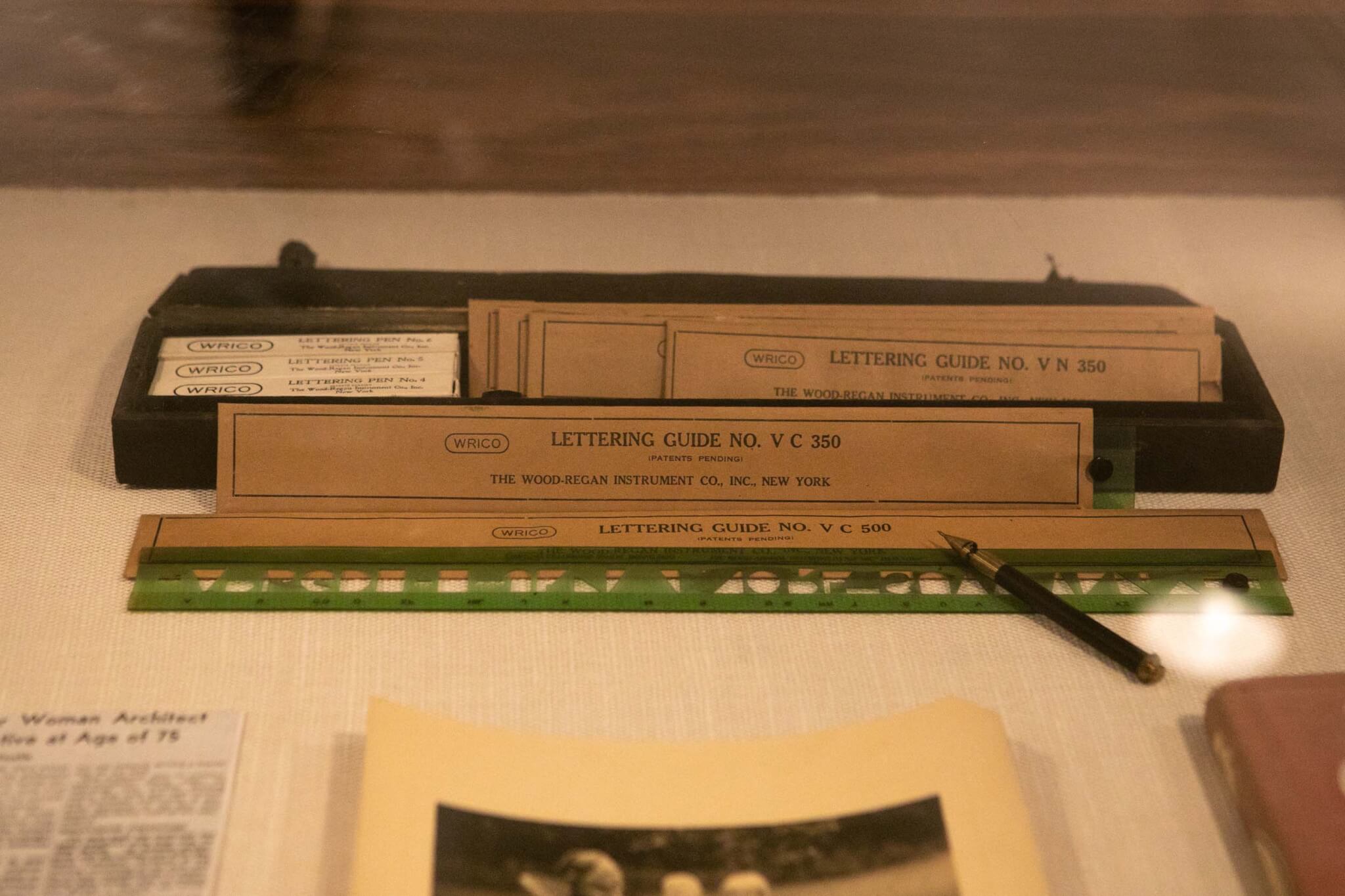

The documents that comprise this history are exhibited in glass-stopped flat-file cases, with informational text adjoining graduation certificates, drawings, and even an 1889 ledger for the Philadelphia developer Wendell & Smith that shows a payment of $23 to Nichols for “sundry plans.” (The text points out that William L. Price and Walter Price, architects also employed by Wendell & Smith, earned $192.50. It’s unclear whether the difference is due to gender-based pay disparity or simply a result of Nichols having completed less work.)

Behind the cases, in magazine racks, Felicella’s unframed black-and-white photographs document more than a dozen residential projects by Nichols as they are today. The images capture the projects straightforwardly, though some focus in on curious details: the underside of a stair that just shaves off the outer edge of a curved molding around an archway (F. Millwood Justice House, 1886–90, Narberth, Pennsylvania), a brick fireplace tucked into a corner created by three walls (William J. Nicolls House, 1891, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania), a set of drawers built into a stair landing (Mary Potts House, 1890, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

In 1891, the day before the completion of the New Century Club in Philadelphia, Minerva Parker married Reverend William Ichabod Nichols. Five years later, they moved to Brooklyn, and Nichols retired from practice. In the exhibition’s concluding text, the curators state that “in reexamining Minerva’s life and profession, we see not a brief career extinguished by the era’s conventions of marriage and motherhood, but rather a sustained lifelong identity as an architect.” Evidence for this claim takes the form of photographs of houses designed by Nichols throughout the early twentieth century for friends and acquaintances, and even one for herself and her husband, built between 1907 and 1909 in Wilton, Connecticut.

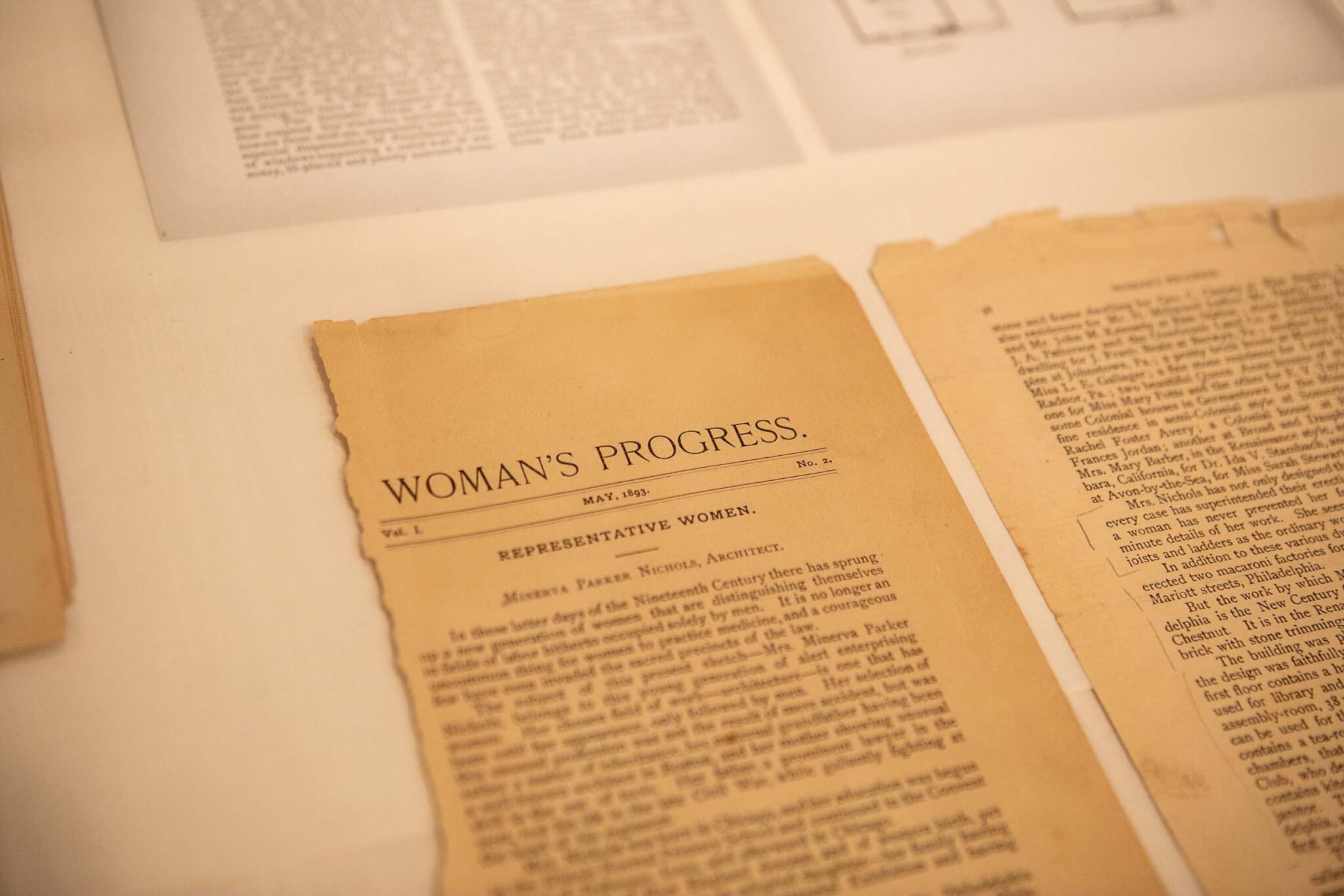

Some of the show’s materials suggest that Nichols’s proximity to women’s causes—she designed a pavilion for the Queen Isabella Association, which advocated for women’s suffrage and equal rights, at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, as well as a house for Rachel Foster Avery, the secretary of the National Woman Suffrage Association—might have influenced her sustained professional activity, though it’s difficult to know for certain. Her life, like that of most of us, resists neat narrative summary. Fortunately, the curators have smartly composed an exhibition that helps the archive speak for itself, displaying a history that, much like the entrance to the archive, could have easily gone unnoticed.

Marianela D’Aprile is a writer in Brooklyn. She is the deputy editor of New York Review of Architecture.