Things You Should Know About Artificial Intelligence and Design

Things You Should Know About Artificial Intelligence and Design

Should designers care about artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning (ML)? There is no question that technology is adding texture to the current zeitgeist. Never could I have imagined seeing a blockbuster hit where Ryan Reynolds emerges as a conscious non-player character in a video game and a flop where Melissa McCarthy negotiates humanity’s future with a James Corden-powered superintelligence within a year of each other. But does learning AI and ML’s ins and outs really matter for the creative professions and our nebulous, invaluable way of operating?

Helen Armstrong, a professor of graphic design at NC State, thinks so. In fact, for her it is imperative. “[AI] is everywhere and has already transformed our profession,” the preface to her new book reads. “To be honest, it’s going to steamroll right over us unless we jump aboard and start pulling the levers and steering the train in a human, ethical, and intentional direction.” The book is Big Data. Big Design. Why Designers Should Care about Artificial Intelligence and its gospel is a primer for designers of all cuts — landscape, graphic, industrial, or otherwise — to get oriented to a brave new world of human-machine relations.

When I say gospel, I do not mean it ironically. Armstrong’s prose is tinged with the passion of an evangelist trying to open our eyes to the great and terrible possibilities of AI-driven design practice. A book of this nature is sorely needed. As Brent Chamberlain and I argued last year in a Landscape Architecture Magazine article, the built environment professions are in the midst of an unprecedented technological transformation that is so overwhelmingly expansive yet so subtle it can be easy to ignore — even if for the mere sake of mental and emotional preservation.

We landscape architects need some particular stirring in this regard. The complexity and timescale of our working medium combined with a mostly healthy skepticism towards new technology for new technology’s sake can sometimes make it seem like the profession is perpetually playing catch-up. Big Data. Big Design. offers the catch-up without condescension, taking the generalist view that every design discipline needs to understand machine learning better regardless of pre-existing technical prowess.

The book’s structure is straightforward, with four main sections sandwiched by a preface and conclusion. The scale of discussion in these sections oscillates between broad definitions of what exactly AI and ML are (Armstrong uses the terms AI and ML interchangeably) and more specific examples of how they are used in design practice.

The parishioner’s tone of the first three chapters then turns more technical in the fourth as the author delves more into the weeds of ML, specifically the differences between its three main approaches: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. If I were to use a crude analogy to sum up the book’s conceptual sequence, I would say it follows Simon Sinek’s golden circle model: it starts with why designers should care about ML, elaborates how designers might use it, and culminates in what such a process might mean for society.

Nearly anyone who lives in the modern world produces data, often on the order of terabytes per day. We text our friends, stream videos, use fitness apps, ask Siri about the weather while we look out the window, walk by CCTV cameras, and the list goes on. Most of these data are unstructured, i.e. not organized in any clear order. Machine learning provides a way for computers to glean meaning from this lack of structure.

As Armstrong puts it, “even now as you read, computers sift and categorize your data trails—both unstructured and structured — plunging deeper into who you are and what makes you tick.” How does it do this? The short answer is algorithms, statistical analysis, and prediction. Not sure what any of those words mean? Fear not! The book is riddled with basic definitions in the margins, inset snappy diagrams, and clear infographics that will bring even the most tech-averse designer up to snuff. For some, these visual aids may seem trite, but to me they were integral.

As a researcher dedicated to demystifying emerging technology for landscape architects, I believe it is vital we get designers of all demographics and digital abilities to a shared understanding of what AI is so we can all better facilitate its continued permeation into practice. Big Data. Big Design. does this is in spades.

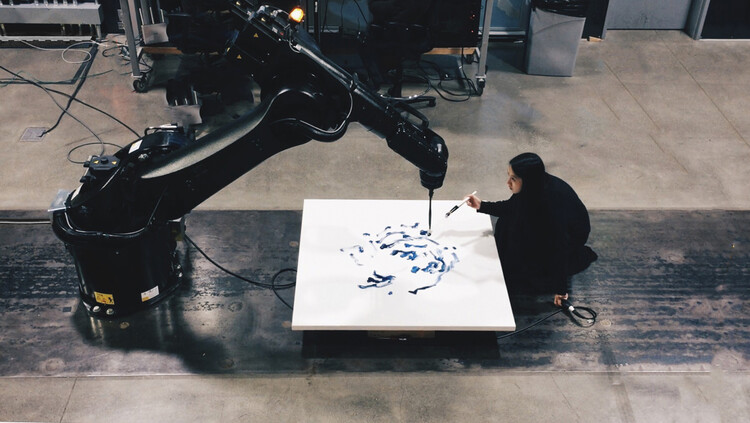

The book’s real strength lies in the compilation of concrete examples from ML-assisted design practice. Armstrong assembles a fantastically broad collection of work exploring this new era of human-machine design that gives support to her claim that “our interactions with machines are shifting from ‘transactional’ to ‘relational’,” and that with that transition comes a fundamentally new way of seeing design.

The reader is introduced to a vibrant, emerging ecology of human-machine design partnerships, envisaging at once all the good that can be accomplished for humanity when those partnerships are well thought out and all the ill that can come when they are not. There are in-depth interviews with human-computer interaction experts like John Zimmerman and descriptions of visionary creative work like that of Tellart and Toyota’s emotionally intelligent concept cars.

Another example: Superflux’s Mitigation of Shock installations portrays a post-humanist model for adapting to climate change.

And Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler offer a mini-essay on AI ethics.

Besides more minor complaints about lumping ML and AI together as one term, which is not my favorite to see as a technophile but tolerable, or a tendency to occasionally slide into less-than-nuanced conjecture about the implications of technology for society, the most glaring fault a landscape architect will likely see while reading is the omission of ML-driven design being produced in our discipline.

While certainly sparser than that of graphic arts, industrial design, or even architecture, human-machine design work does exist in landscape architecture. Landscape architects are using ML to iterate streetscape designs, explore novel approaches to coastal terraforming, and generate high-level urban design concepts, to name a few things. An author professing to speak to all of us ought to do some due diligence on that, and if she did, at least mention it — especially when she resides in a school that includes landscape architects and is theoretically aware of our impact as a design discipline.

Despite this criticism, it is hard to overemphasize the importance and utility of a book like Big Data. Big Design., which takes an overwhelmingly complex and technical subject and translates it into accessible language for designers of any discipline so that we can better understand how it affects us. The increasing spread of AI into every industry means that those who program AI systems in many ways design the societal outcomes those systems produce, even when said systems become completely autonomous. I agree with Armstrong when she writes “we human designers must be there to frame the right problems — the problems that will move us toward future points that truly benefit humanity.”

This article was originally published on The Dirt.