The jagged facade of the Museum of Trendy Aluminum is as dynamic as town round it

Nonthaburi’s new Museum of Modern Aluminum (MoMA), designed by Hung And Songkittipakdee design and research (HAS) gives a new face to Thailand’s history as an aluminum manufacturing hub along one of the busiest thoroughfares outside of Bangkok. While the design team wanted to use the material throughout the building to reflect the museum’s content, the facade also took cues from the existing local urban environment, resulting in an intricate cascade of aluminum bars that incorporates a research-based design approach.

- Architect

HAS design and research - Location

Nonthaburi, Thailand - Completion Date

2022 - Facade Consultant

AB&W Innovation - Aluminum Production Consultant

Goldstar Metal Co., Ltd. - Lighting Design

Light Is - Lighting Products

Neowave Technology - Contractor

SL Window Co., Ltd. - Landscape Design

TROP : terrains + open space

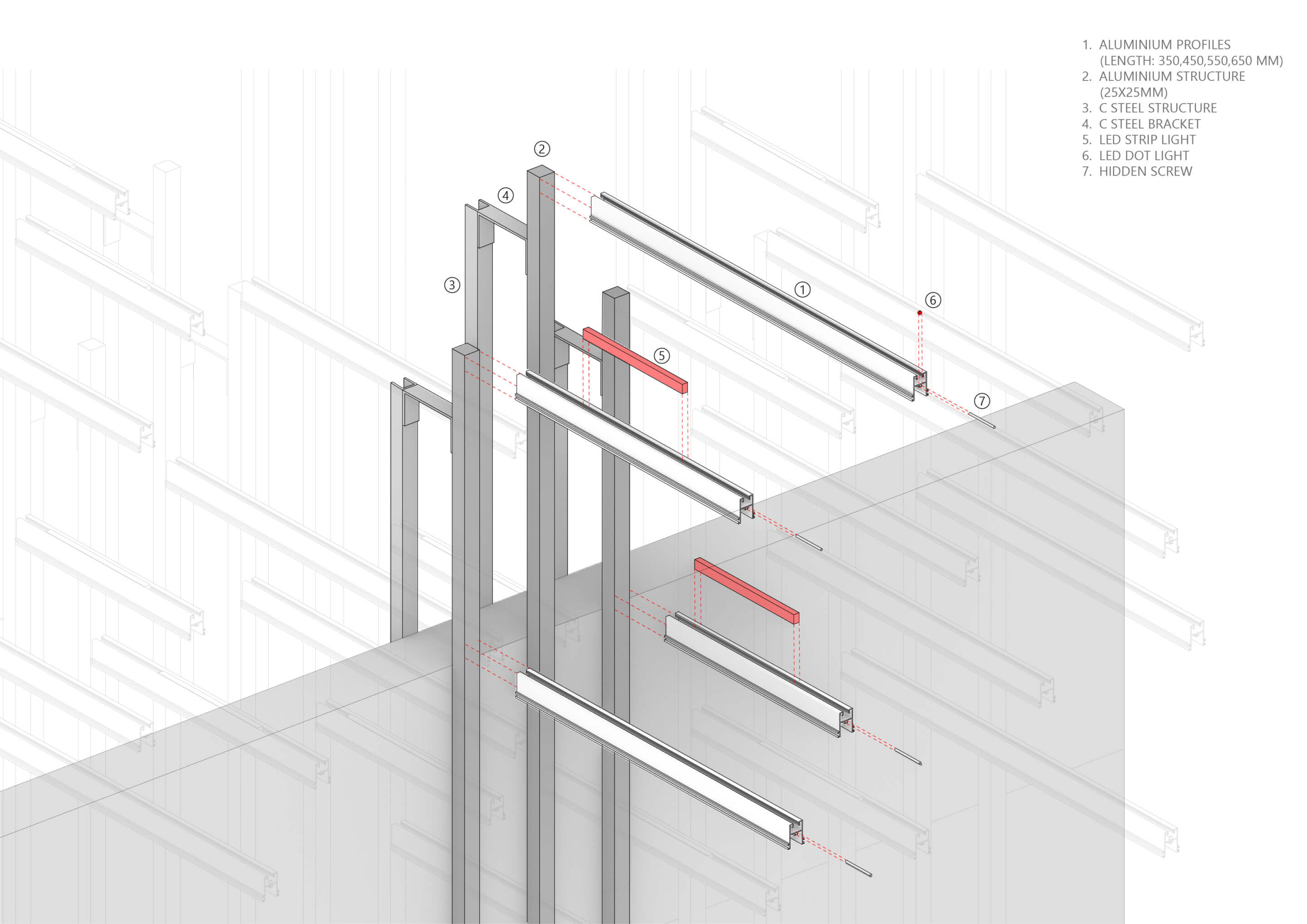

Aluminum strips were used for the facade, to display objects within, across the landscape, in lighting, and in furniture, materially connecting spaces and breaking down the barriers between the museum’s interior and exterior. HAS worked with the Bang Phlap, Thailand-based AB&W Innovation on the structural, electromechanical, lighting, and sun shading components of the facade.

The exterior strips not only provide lighting but pull double duty as passive shading to ensure the comfort of visitors inside. HAS principals Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee said that while their work tends to “blend” the interior and exterior elements of a project, aluminum was a particularly advantageous material for this approach as it is already generally used for both components of buildings. The specific aluminum structural components sourced for MoMA was selected for its ability to provide a sense of proportion when viewed both close-up, and as part of the larger facade system with thousands of elements.

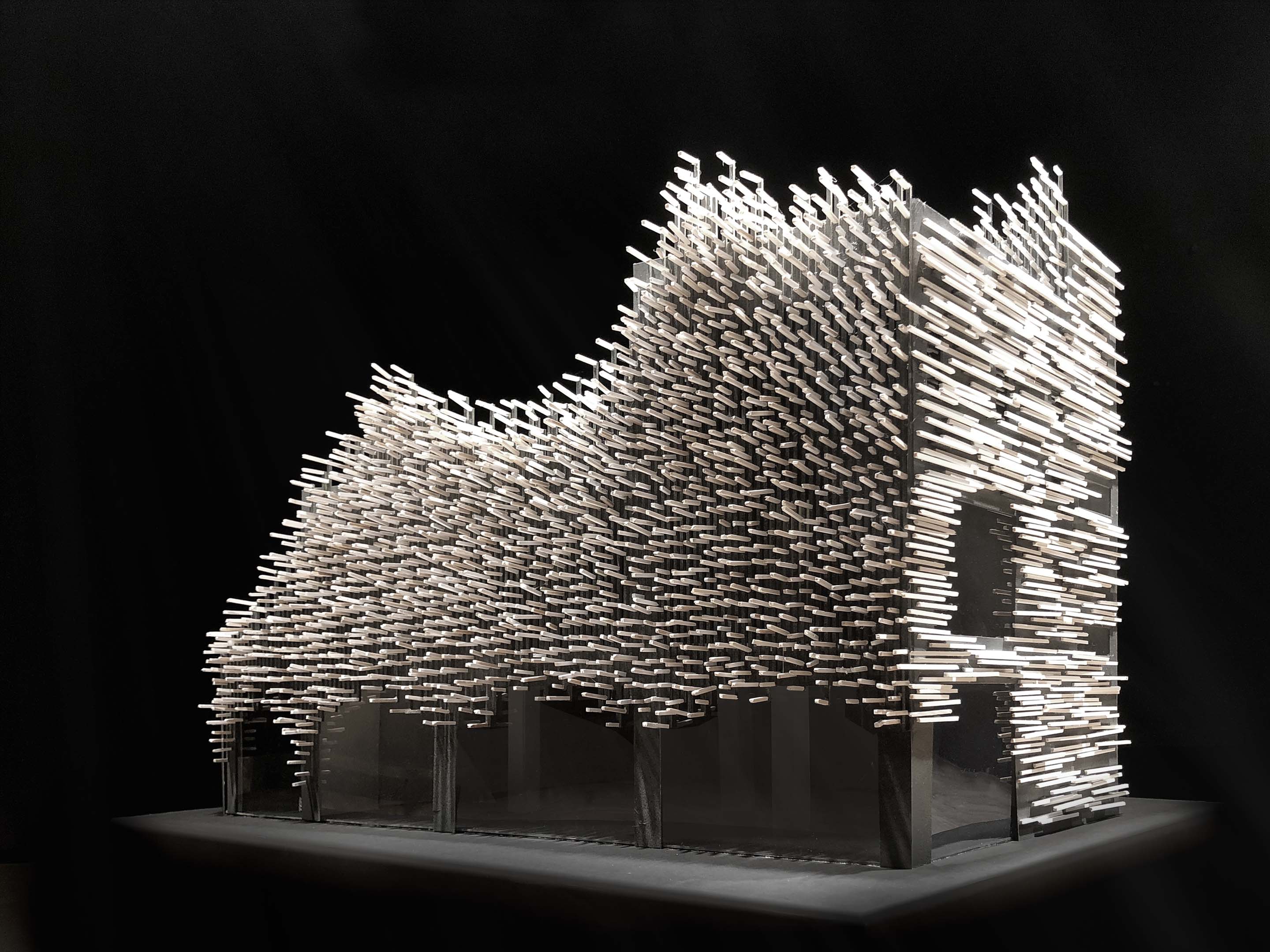

The complex process behind arranging thousands of aluminum strips for the facade was first tested through full-scale mock-ups, working to achieve variances in size and depth for the front-facing and side facades of the building. Across the front facade, four sizes of strips—13.8, 17.7, 21.6, and 25.6 inches (350, 450, 550, and 650 millimeters, respectively)—in length, were grouped together and mirrored, flipped, and rotated in order to realize the pattern system. Once grouped together, LED strips were inserted between the 13.8- and 17.7-inch-long strips. A 1:30 scale physical model of the museum was completed in the final stage of the design process prior to construction to ensure that the pattern diffused light correctly.

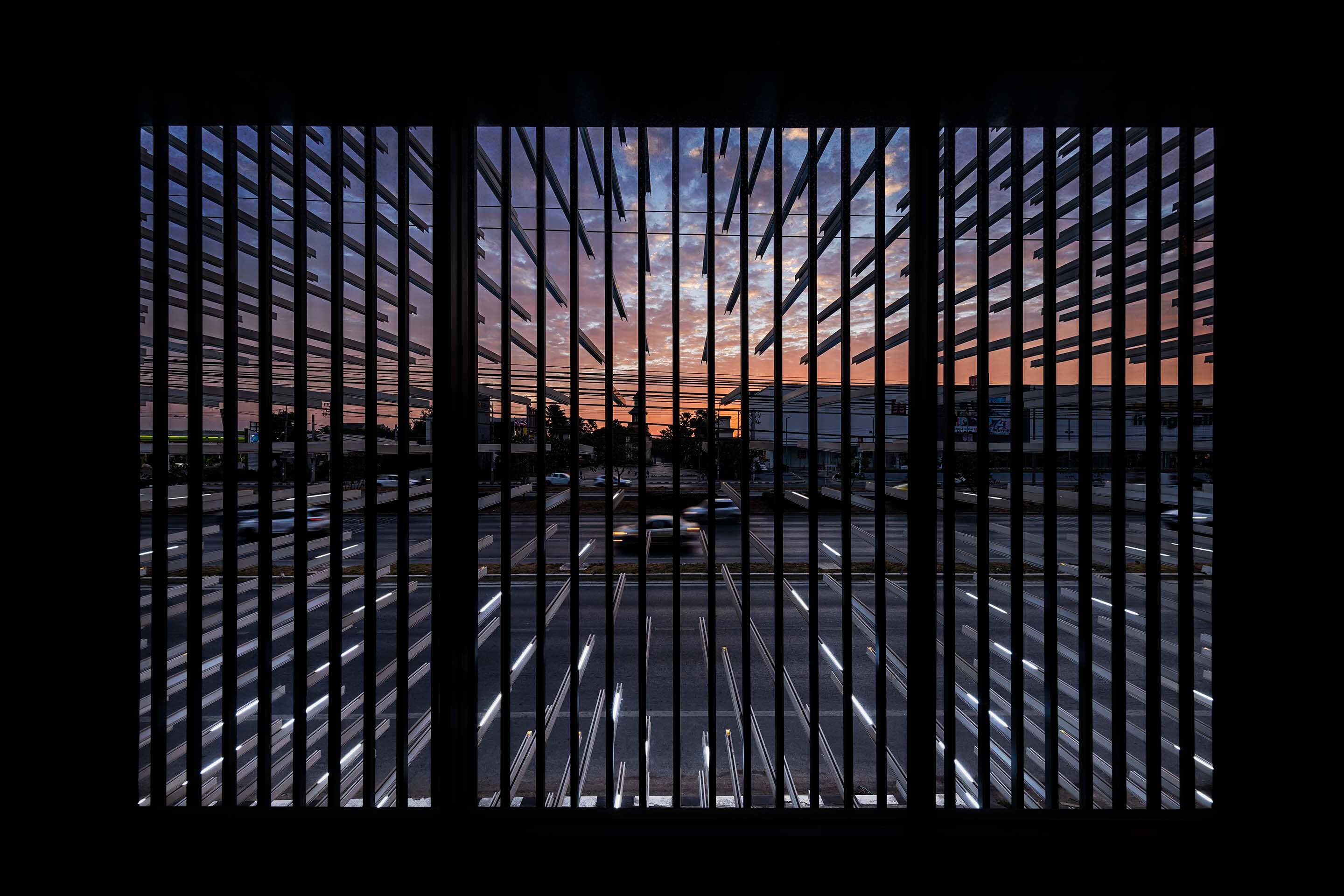

In addition to shading, the aluminum strips of the facade were arranged to create a dynamic shadow on the interior by coloring the strips. As explained by Hung and Songkittipakdee, “When you see the building from outside, which faces the east during the day, you will see the ambiguity of light and shadow on the aluminum strips. However, if you see from inside to outside, the facade creates a pixelated urban image, which gives a new experience to the visitor.”

The intricacy of the effect was realized through the effort of local workers who were experts in an aluminum construction. In order to ensure a high degree of precision during the construction process, the design team also completed 1:1 mock-ups of all of the building’s equipment systems, with special attention devoted to the lighting. In working with the construction team, HAS made slight adjustments to the length of the strips, increasing their density and fortifying the structural integrity of the facade.

The aluminum strips were first cut to the specified lengths, creating the jagged profile that defines the building. The aluminum structure behind them was then installed, with the strips attached using a clip lock method and screws. The architects worked closely with the construction team to push the upper limits of the amount of aluminum used in a facade.

The inspiration behind the jagged profile came from extensive research that HAS conducted in urban areas in Thailand. After looking at the liveliness of advertisements, balconies, and street life, which often incorporate less formal methods of construction, Hung and Songkittipakdee likened the Thai urban landscape to that of a chameleon, with intricate aspects of urban life hidden throughout a larger, dynamic setting defined by a colorful array of lights at night. Given the busyness of the street that MoMA is located on, adorned with “billboards, shopping promotions, real estate advertisements, and commercial displays along both sides of the road,” capturing those aspects of lighting and dynamism became necessary to ensure that the museum reflected the urban setting it was constructed in.

Additionally, HAS’s research concluded that the use of metal in building skins—apart from the context of a museum celebrating aluminum—made for interesting experimentation given that metal products in buildings in the area were mainly featured in interior spaces like door frames and structural components. The potential of using metal solely for its appearance was previously left largely ignored. In adding metal to the facade of MoMA, HAS ultimately sought to show the power of using materials that would normally be reserved for structural or performance aspects to create a unique profile.