The Ion in Houston upgrades an art deco Sears into a tech-incubating cyborg

The blocks surrounding Houston’s old Main Street Sears have seen better days. When the department store opened in 1939, this section of the Fourth Ward, which is just south of downtown, was a quiet suburban neighborhood. Commercial storefronts lined the thoroughfares, and quaint bungalows nestled along the tree-lined streets. It may as well have been Mayberry, to hear some old-timers tell it.

Things took a turn for the worse in the 1960s, during the construction of the I-45 and U.S. 59 freeways. Thousands of homes, businesses, and churches were seized by eminent domain and demolished—particularly in the neighboring Third Ward, which was and is predominantly African American—while tens of thousands of people fled the area to new developments dispersed along the high-speed ribbons of concrete. The community was shattered. What businesses remained found themselves starved of customers. Many shuttered permanently. Others limped along, a shadow of their former selves. Economic depression set in. Crime shot up. In a particularly vivid sign of the times, Sears sheathed its once-proud art deco facade in a corrugated metal slipcover and filled in its shop windows with bricks.

What’s remarkable is that the Main Street store continued to operate in this condition until 2018, when the ailing retailer filed for bankruptcy and pulled out. By that time, the neighborhood itself was reduced to trash-strewn vacant lots and derelict buildings where people experiencing homelessness and drug addiction squatted and wandered through the roaring sound of the rushing freeway traffic like lost souls in search of the community that once thrived there.

It was a truly depressing situation. So completely depressing, in fact, considering the barbarism and racism that underpin the urban design moves that created these circumstances, that you almost have to approve of what is happening there now. Almost.

Even before its shuttering, Rice Management Company, which shepherds Rice University’s $8.1 billion endowment, acquired the remainder of the ground lease on the old Sears and assembled some 12 other more or less contiguous plots. The purpose of this investment was the planning of an “innovation district” to incubate tech start-ups. Houston, it must be noted, was the largest city in America not to make Amazon’s 20-city shortlist of potential sites for its second headquarters. Places like Indianapolis and Columbus, Ohio—even Dallas!—beat out the Bayou City. This gave way to some soul-searching among Houston’s elites, who, Amazon or no, were already trepidatious about the future of the oil and gas industry. What the city needed, they decided, was a centralized hub where investors could meet ambitious young makers working in the areas of energy transition, medicine, and aerospace—a nurturing environment where the future of Houston’s economy could take root and grow.

The Main Street Sears was the perfect spot. For one, the department store’s large, 58,000-square-foot floor plates—a rarity in Houston—were ideal for creative office space. It’s also located on the light rail line halfway between the city’s two largest employment centers: downtown and the Texas Medical Center. What’s more, the surrounding land was up for grabs and not yet overrun by the gentrification marching south through Midtown. Rice rechristened the old Sears “The Ion” and hired SHoP Architects, along with Gensler, John Carpenter Design Associates, and James Corner Field Operations, to transform the aging structure into the anchor space of a new city center dedicated to evolving the local economy.

This is The Ion District. An ion is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge, which can be positive or negative. Ions are used as catalysts in chemical reactions, which is why Rice chose this name, though the bipolar nature of these particles says more than what was intended.

Houston’s legacy of historic preservation is lackluster. For that reason, the client and the design team must be commended for seeing the value in restoring the art deco facade. But only the north and half of the east and west facades had any fabric worth saving. The rest of the building was always more service-oriented, and the whole thing was almost entirely windowless. To compete as creative office space, daylight was needed on the interior. So the choice was made to glaze most of the building, including the two upper floors that were added to make the real estate equation work, and large windows were cut into the restored envelope. The resulting composition looks sort of like a giant, abstracted rendition of RoboCop’s mug—the back and upper regions encased in high-tech metallic blue glass shaded by perforated metal fins, the lower front showing what remains of the human within.

RoboCop, as awkward as he was, had a lot of charisma. (Incidentally, RoboCop 2 was shot in Houston, while the first film was made in Dallas—both cities filling in for a future Detroit imagined as even more dystopian than the present one.) The same is true of The Ion. The landscaped plaza that fronts the building features two heritage live oaks whose broad boughs shade plentiful seating, which, during my visit, was being amply used by people on their lunch breaks. Additional plantings were selected to attract charismatic insects, like the ladybug that flew into my partner’s fingers as we stood there. The preserved face of the building at street level is home to hospitality spaces, including restaurants, a cafe, and a soon-to-come “taproom.” They make this tech incubator also a destination for regular Houstonians looking for a bite or a drink.

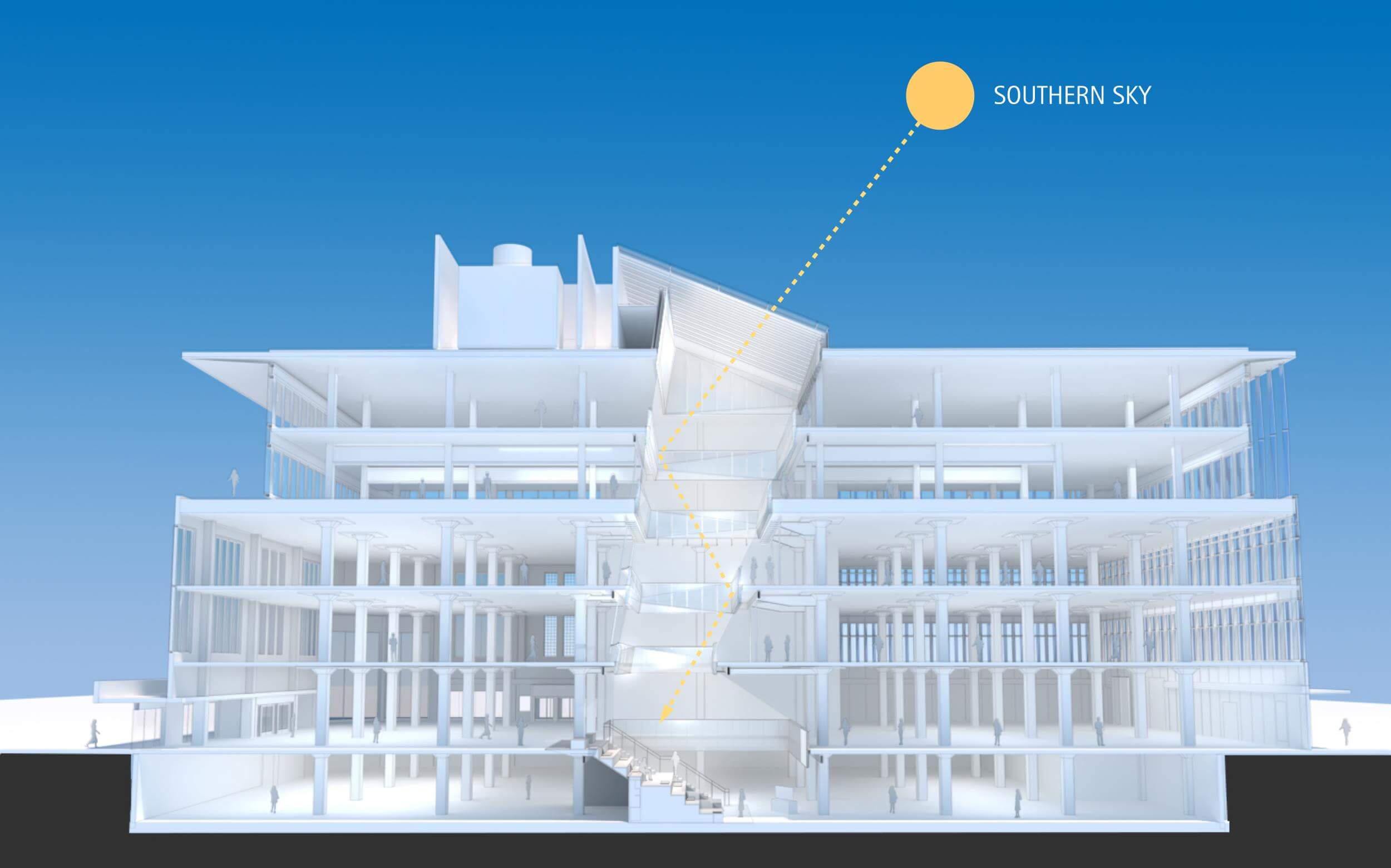

Inside, the existing concrete structure is left exposed, as are the department store’s worn terrazzo floors. These patinated surfaces, as humdrum as they may be in the grand scheme of things, exude an aura that can’t be re-created in new construction. An atrium cut into the middle of the floor plates admits a controlled but consistent amount of daylight, which pours down from a skylight tilted to the south and outfitted with fixed louvers. This light, which has a silvery quality to it, is refracted throughout the space by perforated aluminum panels that ring the atrium, reaching all the way down to The Ion’s lower level (they don’t use the “b” word, I was told), which can be accessed by a “forum” stairway. The lower level is where start-up entrepreneurs begin, engaging in workshops and refining their pitches. On the first level, in addition to the hospitality spaces, are an investors’ suite and a large makerspace outfitted with 3D printers and the like. The second level hosts a co-working office. On the third are smaller leased spaces for companies that have moved past the initial incubation phase. The fourth and fifth levels are reserved for large tenants. Throughout the stack, the floor area around the atrium is meant to remain publicly accessible, the goal being to create a lively buzz up and down The Ion’s core.

Though only 52 percent leased during my visit, The Ion was indeed lively with what I took to be young entrepreneurs cooking up schemes for the future. Microsoft and Chevron had moved into the building, the first large corporations to stake their claim to the innovations that will presumably be fusing here as in a particle collider. The district that will grow around this catalyst building will, I guess, offer the sort of mixed-use urbanism that attracts enough talent/money density to precipitate a reaction and ignite a new economy, one that is hopefully a lot greener than Houston’s oil and gas addiction. But what other reactions will The Ion catalyze? Is this just the walkable-urbanism version of the freeway in terms of the displacement it may cause in the Third Ward? And what of those lost souls who now wander in its shadow, prevented from even cutting through the parking lot by a high chain-link fence? Will they reap the benefits of the innovations taking place here or be blown away like so many dead leaves before the lawn man’s blower?

Design architect: SHoP

Architect of record: Gensler

Location: Houston

General contractor: Gilbane

Structural engineer: Walter P. Moore

Facade consultant: James Carpenter Design Associates

Landscape architect: James Corner Field Operations