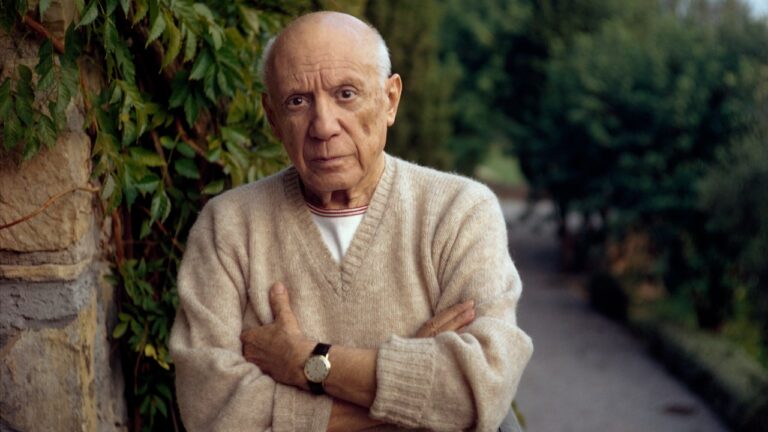

Pritzker Prize winner Richard Rogers dies at 88

Pritzker Prize and multiple Stirling Prize winner, AIA Gold Medal recipient, architect, urbanist, forward thinker, governmental advisor, humanist, and eclectic dresser Richard Rogers has passed away at the age of 88 at his home in London. His December 18 death was confirmed by his son Roo Rogers in the New York Times, though the cause was withheld.

Born to Anglo-Italian parents in Florence, Italy, in 1933, Rogers’ parents fled to London in 1939 when he was six as war encroached on Europe. There, Rogers struggled to fit into boarding school due to his undiagnosed dyslexia and sunk into depression, and he would struggle to fit in until a visit to his cousin Ernesto Rogers’ BBPR office in Milan in 1953; the elder Rogers was already a well-respected architect and planner, and this was Richard’s first exposure to the field. He enrolled in the Architectural Association School (AA) in London in 1954.

It would be Rogers’ tenure at Yale, and the opportunity to see America the followed, that would change everything. He and his wife Su Rogers crossed the Atlantic in 1961 to attend Yale, where a friendship with fellow student Normal Foster and tutelage under architectural historian and scholar Vincent Scully, would radically alter the trajectory of Rogers’ life.

In a 2018 interview with AN, Rogers recounted his weekend trips into New York City with fellow AA alumnus James Stirling, where he was “blown away” by the sheer size and scope of Manhattan’s modernist towers—the Seagram Building, Lever House, 270 Park Avenue, and a sea of glassy International Style buildings had only just sprouted up across Midtown less than a decade prior. After graduating, Richard, Su, and Foster would travel across the U.S. to study further examples of Mies and Frank Lloyd Wright firsthand, as well as the Case Study Houses in California. The trio returned to London in 1963, adding Foster’s future wife Wendy Cheesman to the group and forming their own firm, Team 4.

Although Team 4 would dissolve in 1967, the Rogers launched their own firm soon afterward that, along with a young Renzo Piano, would respond to a Parisian competition brief that would change everything. Inspired by Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, the often referenced but never built mutable, multipurpose venue, the team would submit a proposal for the “inside-out” Centre Pompidou in 1971. The “inside-out” contemporary arts center opened as a home for the Musée National d’Art Moderne in 1977, with massive uninterrupted floor plates thanks to the monumental building’s High Tech exoskeleton. The center was, at the time quite divisive, inspiring protests over both the center’s unqiue design and gentrification it was bringing to Paris’s Les Halles neighborhood. The postmodern multicultural center has proven a massive, unexpected success in the years since, spawning international branches worldwide (including a forthcoming Jersey City location).

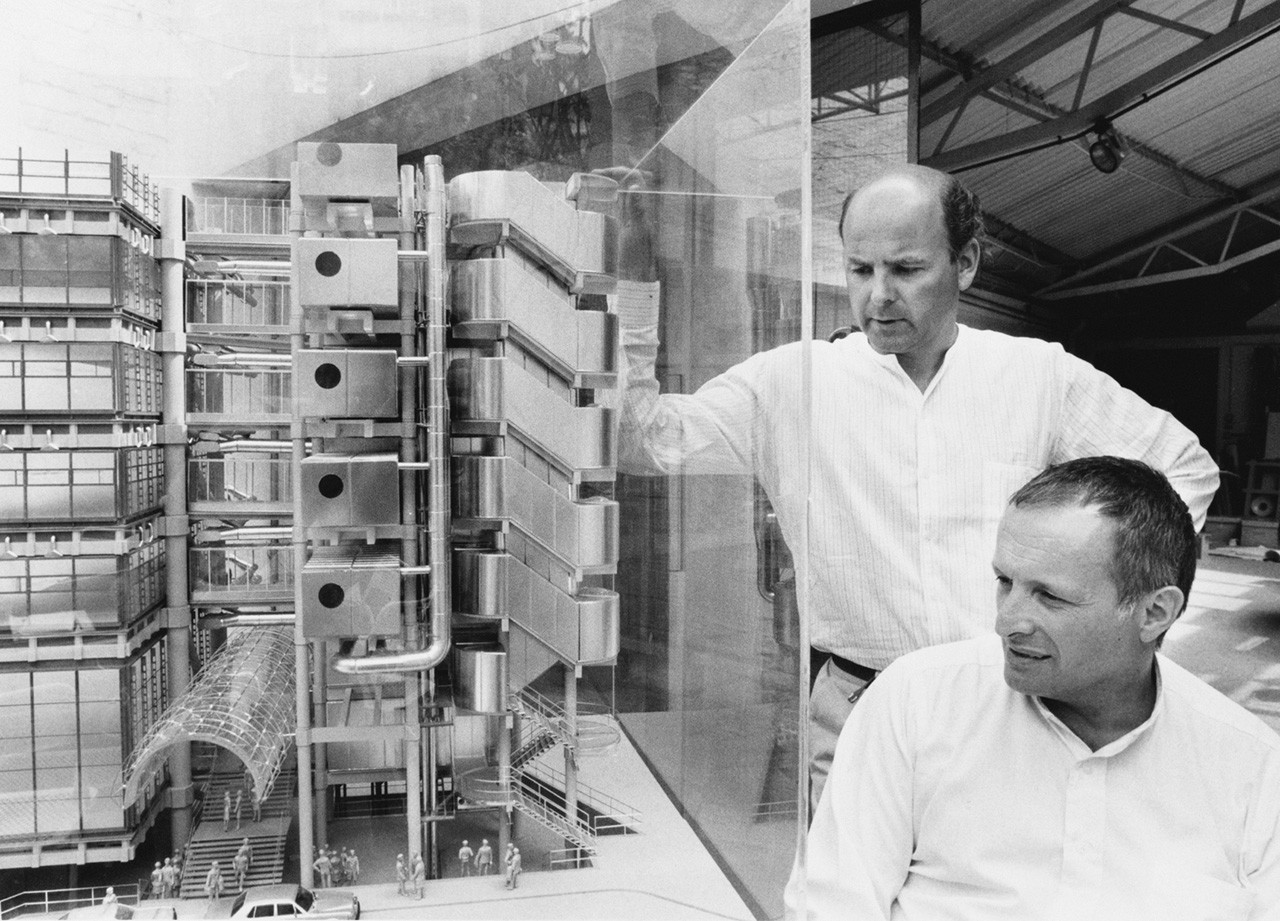

Parlaying that momentum, Rogers’ would follow up the Centre Pompidou with what some have called his greatest work, the Lloyd’s of London headquarters, through his new firm, Richard Rogers Partnership. Although he had never designed an office building before, Rogers took to the commission with vigor, marrying skeletal tresses, over-exaggerated heating and cooling duct imagery, and a Victorian-inspired glass barrel vault topper containing an atrium with the massing of a traditional tower.

Rogers’ firm would undergo a renaming to Rogers, Stirk, Harbour + Partners (RSHP) in 2007 to celebrate the company’s collaborative nature. In that time, they’ve designed everything from 3 World Trade Center at 175 Greenwich Street, a glassy tower with subdued traces of trademark exteriority to set it apart from its neighbors; the pleated International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C.; the Stirling Prize-winning Maggie’s West London Centre, and many, many more from offices to bourbon distilleries to high-end residential towers.

Rogers officially retired from RSHP in September of 2020, ending a fruitful 43-year career to spend more time with his family. All of this is to say that he leaves behind too long a list of accomplishments to recount in this announcement of his death (to say nothing of London’s Millennium Dome, the Inmos Microprocessor factory in New South Wales, his earlier work in 1967 on Reliance Controls, or his planning recommendations for the English government), but suffice it to say, each project expresses an unwavering clarity of vision.

AN will follow this breaking news story with a longer obituary and remembrances from those close to Rogers. In the interim, Todd Gannon recounted in depth why Rogers’ influence will be felt long after his passing last year upon news of his retirement—in light of new events, the piece also serves as a memorial and testament to his power to inspire.