Never Alone explores five decades of video game history at MoMA

Never Alone

Museum of Modern Art

New York

Through July 16

As the world around us becomes more and more integrated with technology, it’s easy to overlook how much our interfaces, and the programs we use, have evolved. From Windows and Mac icons to the ubiquitous power symbol, the design language of interactivity has become refined and ever more invisible.

Nowhere is this more evident than in video games and the devices we use to play them. At Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design (running through July 16, 2023, in the museum’s public free gallery), the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has drawn from its permanent collection to catalog those games and platforms with an architectural eye. Organized by Paola Antonelli, senior curator in the museum’s Department of Architecture & Design, Never Alone is interested in charting how novel interactivity becomes mainstream.

Since 2006, MoMA has amassed a collection of interactive design objects. The archive has since grown to encompass “intangible” objects such as the @ symbol, the Google Maps Pin, and Minecraft, alongside 85 other pieces of software at the time of writing. Although rarely seen outside of exhibitions about interactive or narrative design, the museum has continued collecting as video games continue to evolve—perusing what’s on display at Never Alone is by design familiar, as the games and devices on display include present-day entries.

Entering on the ground floor, visitors are first greeted with the internationally accepted symbol for power—a near complete circle intersected with a vertical bar at the top—as a massive wall decal. Despite its ubiquity, the symbol was only recognized as a universal icon in 2002 at the behest of the International Electrotechnical Commission. A simple combination of the symbols for “open circuit” and “closed circuit” first used in 1973, it was only canonized thirty years later. That’s placed squarely next to the original 2001 iPod designed by Jonathan Ive. Although not on display in Never Alone, the design eventually iterated into the familiar iPhone. Though the physical scroll wheel is gone, newer models still retain vestigial traces of their original shape and UI design.

XO Laptop from 2005’s ill-fated One Laptop per Child (OLPC) initiative is nearby. Pentagram completed the simple UI for the rugged, low-power device. While OLPC failed for myriad reasons (a combination of political and technological), the concept isn’t dead: Today, low-cost, low-power laptops are in wide use for education and the OLPC still exists.

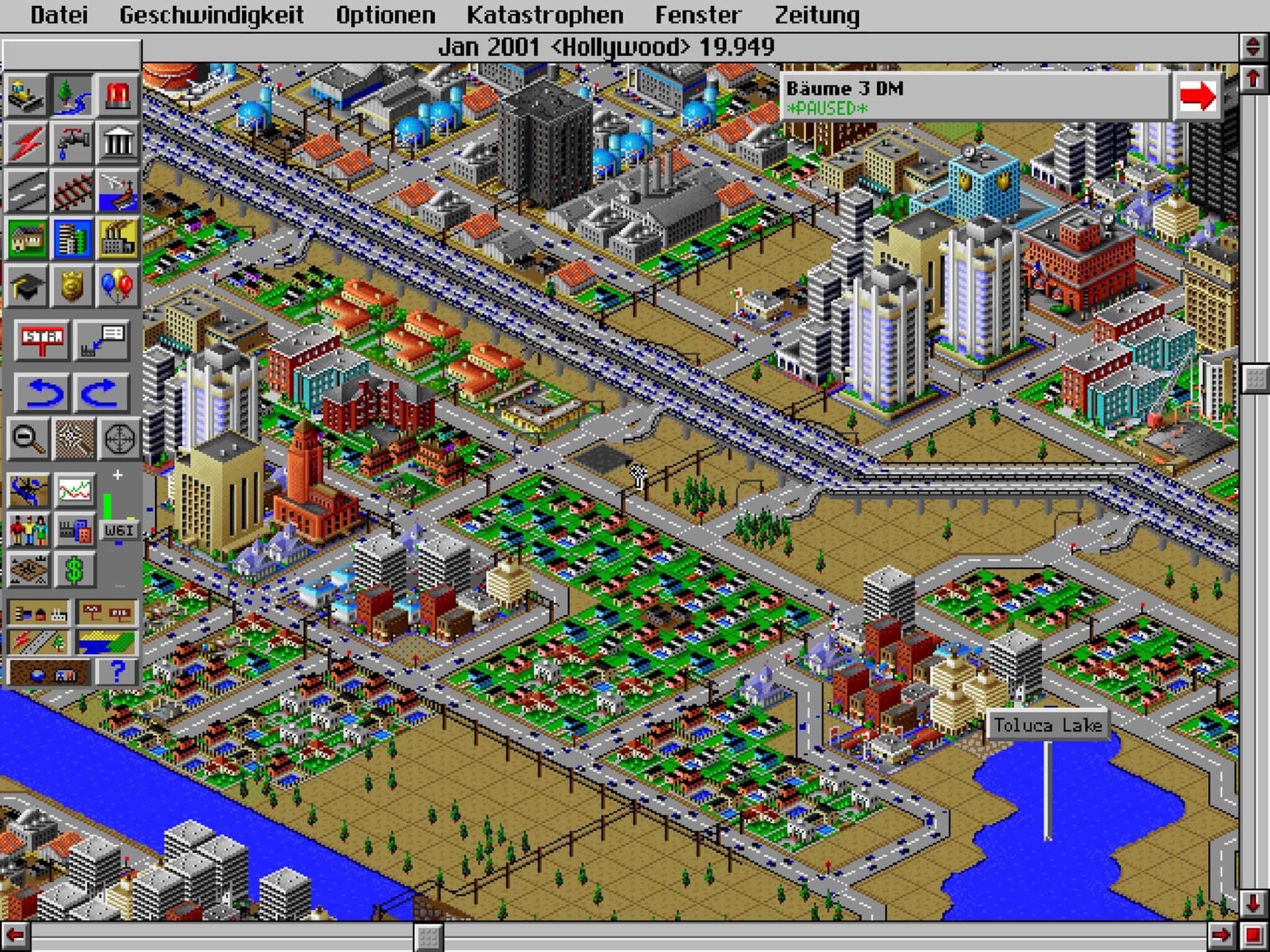

Never Alone is interested in evolution, and nowhere is that more evident than in the selection of games on display. The massive poster on the West 53rd Street window advertising the show runs through the 30 games from the MoMA’s permanent collection in Never Alone, and it’s broad enough to interest even those with only a passing knowledge of games. If you haven’t heard of the historically accurate, monochromatic mystery game Return of the Obra Dinn, maybe the media buzz around Dwarf Fortress has piqued your curiosity. If not, it’s more than likely you at least know Minecraft or SimCity 2000, or at a bare minimum, Pong.

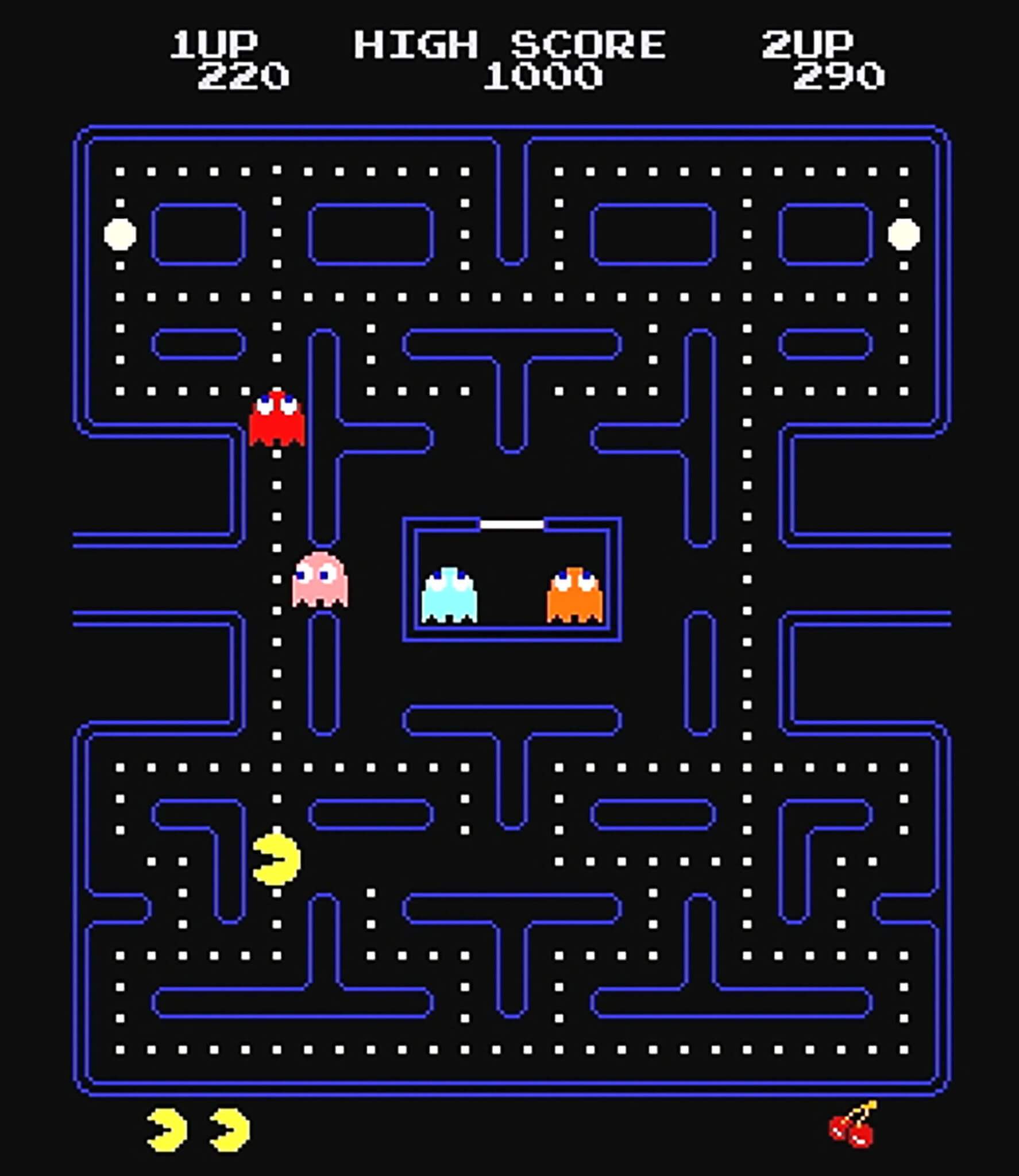

Even more enticing is the ability to play them firsthand inside. Although Pong wasn’t the first video game ever released when it debuted in 1972, it was the first major success despite only having one-dimensional controls: The paddle moves up or down, and that’s it. The physical controller is correspondingly simple. As games became more advanced, the inputs used to control them evolved simultaneously, and vice versa. Larger memory caches and more advanced graphical processing abilities led to games like 1980s Pac-Man, which necessitated an eight-directional stick and additional buttons.

Flash forward to today, and controllers are wireless, have multiple thumbsticks, triggers, back paddle buttons, and motion controls—and all of those inputs are put to use. It makes sense in a world where games like Minecraft, which offers a blank slate of infinite architectural possibilities and a correspondingly large inventory of building materials, have become the norm.

Being able to play most of the games lends Never Alone a tactility that simply reading about the games on display would lack. The curatorial decision of allowing viewers to become gamers—you can, for example, pick up a PlayStation 2 controller and roll through Katamari Damacy, a game where you collect everyday objects and get larger and larger until you’re sucking up entire galaxies—lets visitors experience the same technical control challenges that the developers had to work around. At least it would in theory; a few of the kiosks were out of order when I visited, and circulation through the gallery was congested as visitors waited in line to play games.

Still, there are more than enough interesting physical objects on display to warrant a visit, even if Never Alone argues that the intangible side of interactive design is just as important. Just because something doesn’t exist in the real world doesn’t mean that it sprung fully formed from the ether. Everything on display in Never Alone was designed by a human, with the intent of fostering human connection, whether it be engaging with a game’s systems or other players. My personal favorite piece is Prayer Companion, a scrolling digital signboard that alerts nuns in York, England, otherwise cut off from the outside world due to their vow of enclosure, about contemporary problems plaguing the world that they should pray for. It’s at once novel, anachronistic, and fun.

That’s mostly what good interactive design should do: Like a well-thought-out building, it guides attention and has a specific purpose for the user, even if it’s a game and the end goal might be obfuscated. Unlike a building, it’s also seamless, invisible, and not constrained by things like gravity or waterproofing. Unless you’re a habitual collector (or hoarder) of old electronics, Never Alone is a rare opportunity to see a timeline of important and ubiquitous gaming objects.

Jonathan Hilburg is an electronics editor at Reviewed who focuses on gaming. Previously, he was The Architect’s Newspaper‘s web editor. He lives in Manhattan and is keenly interested in the intersection of art, architecture, and context.