NASA’s webb telescope captures deepest + sharpest images of the distant universe so far

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope

On July 12th, NASA unveiled its recent breakthrough as James Webb Space Telescope photographs full-color images and spectroscopic data of the universe’s glittering landscape and dying stars. Brought together by international collaborations with Space Telescope Science Institute, European Space Agency, and Canadian Space Agency, NASA dubs the deepest infrared views of the universe ever seen in the present as the dawn of a new era in astronomy.

The hollow, void-vacuumed space in the past has now seen the light through the myriad of star-forming regions, galaxies, and dusts that swivel in space. Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) feature crisp resolution and high sensitivity that manage to photograph hundreds of previously hidden stars and background galaxies, carving a path for the space agency teams to uncover the cosmic views in its best resolution and continue to conduct studies on the universe, light-years away.

all images from NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI | header image: Cosmic Cliffs | image: SMACS 0723

NASA’s Webb telescope captures Cosmic Cliffs

Images of Cosmic Cliffs (header image) shed light on how stars form. Its rippling orange dust colludes until it mirrors rocky mountains and hills in desserts and blue smokes rise out in the background, a gossamer over the hundreds of stars. This star-forming region called NGC 3324 in the Carina Nebula has been carved from the nebula by the ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from extremely massive, hot, young stars located in the center of the bubble. The searing ultraviolet radiation from the young stars constructs the nebula’s wall by slowly wearing it away.

Pillars resist the radiation and tower above the wall of gas, and the steam that emerges from the celestial mountains is hot ionized gas. Because of the relentless radiation, hot dust streams away from the nebula. The birth of stars spreads over time, caused by the eroding cavity’s expansion. The bright, ionized rim slowly pushes into the gas and dust as it travels into the nebula. If the rim comes into contact with any unstable material, the increasing pressure causes the material to collapse and generate new stars.

NGC 3132 / Southern Ring Nebula

NASA’s Webb telescope and the dying stars

The details of the Southern Ring planetary nebula (image above) reveal a faint star positioned in the middle has been sending out rings of gas and dust for thousands of years in all directions. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope captured its image and identified that this star, which is covered in dust, expels clouds and gas, an indication of a dying star. NASA explains that each shell of the dying star represents an episode where the fainter star lost some of its mass.

‘The widest shells of gas toward the outer areas of the image were ejected earlier. Those closest to the star are the most recent. Tracing these ejections allows researchers to look into the history of the system,’ NASA writes. The telescope also photographed fine rays of light around the planetary nebula, and starlight from the central stars streams out where there are holes in the gas and dust. When the star releases shells of material, dust and molecules form within them, and the expelled dust may end up in space and be incorporated into a new star or planet.

SMACS 0723

NASA’s Webb telescope and galaxy SMACS 0723

Galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 (image above) brims with thousands of galaxies. Imagine a grain of sand held at an arm’s length – this is the approximate size of a galaxy in this image. This deep field is a composite made from images at different wavelengths, and researchers will continue to use Webb to take longer exposures and reveal more of the vast universe. This image shows the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago, with many more galaxies in front of and behind the cluster.

As NASA explains, light from these galaxies took billions of years to reach mankind, and the public now sees a time within a billion years after the big bang when viewing the youngest galaxies in the field. ‘The light was stretched by the expansion of the universe to infrared wavelengths that Webb was designed to observe. Researchers will soon begin to learn more about the galaxies’ masses, ages, histories, and compositions,’ says NASA.

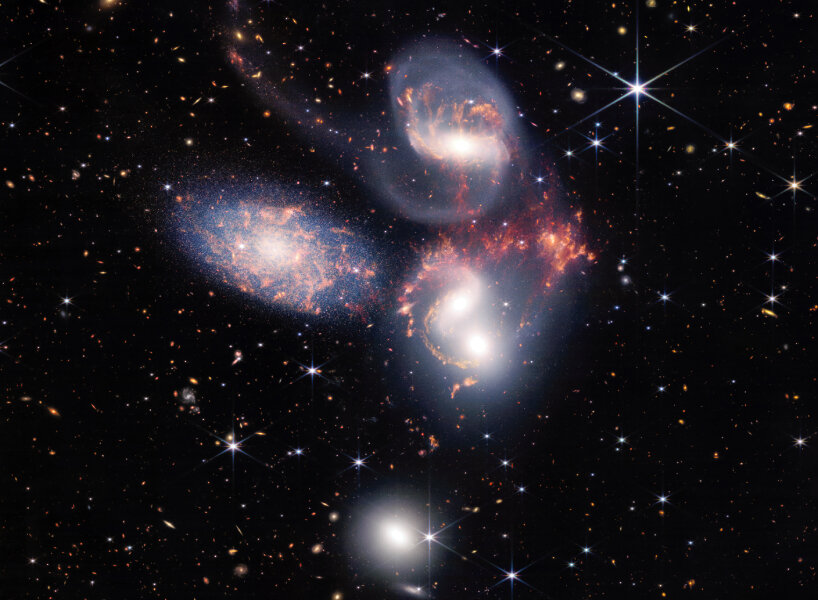

Stephan’s Quintet

NASA’s Webb telescope captures Stephan’s Quintet

The next image NASA’s Webb shares is the never-before-seen details of the galaxy group Stephan’s Quintet (image above), a visual grouping of five galaxies. The mosaic-looking image covers about one-fifth of the Moon’s diameter and contains over 150 million pixels, constructed from almost 1,000 separate image files. Clusters of millions of young stars and starburst regions of fresh star birth with tails of gas and dust.

NASA shares that Webb also captures huge shock waves as one of the galaxies, NGC 7318B, smashes through the cluster. Although called a quintet, only four of the galaxies are close together and caught up in a cosmic dance as the fifth and leftmost galaxy, called NGC 7320, is in the foreground compared with the other four. For NASA, studying such relatively nearby galaxies like these helps scientists better understand structures seen in a much more distant universe.

NGC 3132 / Southern Ring Nebula