Mapping Improvisation: The Function of Name and Response in City Planning

This article was originally published on Common Edge.

New Orleans was designed by its early settlers in 1721 as a Cartesian grid. You know it as the famous French Quarter or Vieux Carré. Such grids are named for the Cartesian coordinate system we learned to use in algebra or geometry class, perpendicular X and Y axes, used to measure units of distance on a plane. The invention of René Descartes (1596–1650), these grids reflect his rationalism, the view that reason, not embodied or empirical experience, is the only source and certain test of knowledge. William Penn used a similar grid in 1682 in selling Philadelphia as an urban paradise where industry would thrive in the newly settled wilderness. And just as the massive buildings of Italian Rationalist (i.e., Fascist) architecture express authoritarian control, so, too, Cartesian grids implicitly say: Someone is in charge here. We’ve got this. Trust us.

Vieux Carré vs. Congo Square

Related Article

It is said no artist can draw a perfect circle freehand. You might come to know a circle by examining the handmade glass in your hand with its more-or-less circular rim. A Cartesian system tacitly says that you can know a circle better, that you can know it with perfect certainty, when it is drawn on the X and Y axes and expressed as a rational principle: 2πr. For Descartes, certainty matters. His quest for the grounds of perfect certainty is the foundation of modern philosophy, Western culture’s dominant effort to know the world.

For the early settlers of New Orleans, the inhospitable, flood-prone geography cannot have seemed very certain; the first spring after the city’s founding, the Mississippi overflowed its natural levees. The grid, installed two years after that flood, was an effort to make sense of and to constrain the strange, semitropical wilderness in which the French settlers found themselves.

In New Orleans, nature even seems to fight the rational compass. Because the grid was sited in a bend in the river, the sun rises over the west bank. On maps, South Rampart Street is upriver from North Rampart. The grid reflected the quest for rational order and certainty that Descartes and his countrymen put their faith in. It would not be until late in the same century before Jean-Jacques Rousseau would call such faith in doubt, giving birth to the Romantic worship of things natural, wild, even savage.

The French name for the French Quarter, Vieux Carré (Old Square), still used today by tourist brochures, emphasized the grid. True to the spirit of Cartesian rationalism, the seats of power clustered at its center. The Place d’Armes, now Jackson Square, where the militia mustered and trained, was the center of military power. In front of it lay the St. Louis Cathedral: ecclesiastical power. At the church’s side lay the Cabildo: political power. The Louisiana Purchase was signed there in 1803, transferring power from Napoleon’s France to Jefferson’s America.

Given the Cartesian roots of this grid, it’s possible to imagine that its power nexus projects an axis pointing away from the river. Follow that axis north on present day Orleans Street and you come just beyond the grid to Place Congo (Congo Square), now a Live Oak grove in a city park named for native son Louis Armstrong, the man who perfected the improvised solo in jazz. Place Congo lies in “Back a’ Town,” so-called because it is beyond the city’s once-proposed but never-built ramparts, meant to keep out seasonal floods and the sometimes-hostile Native Americans from the backswamp, the pristine, old-growth cypress swamp between the grid and Lake Pontchartrain to the north. In this old map, it doesn’t even merit a mention.

Were you to walk along this axis a century after the city’s founding, you might get the impression that civilization had won the battle over nature’s uncertainties and wildness. You’d pass near the Theatre de la Rue Saint Pierre, where, since the 1790s, plays were performed in French, that language said to be the most rational. Sylvain, the first opera performed in the New World, premiered there in French in 1792. You’d pass near the future site of the French Opera House, architect James Gallier’s elegant, symmetrical neoclassical building, the centerpiece of New Orleans’ thriving social scene.

If the grid marked the civilized world and the Opera House was its apex, Place Congo, there at the backswamp’s edge, was where, to the settlers at least, the uncivilized world nevertheless encroached. As late as the 1880s, local colorist George Washington Cable described the backswamp, or marais perdu (lost swamp), that surrounded Place Congo as a “poisonous wilderness on three sides” (“The Dance in Place Congo”). A. Baldwin Woods’ newly installed screw pumps would save the city from flooding from the Hurricane of 1915 and enabled swampland reclamation and development of much of the land now occupied by the city.

Before the arrival of Europeans, what became Congo Square had been a marketplace, a sacred space where “Native Americans celebrated their corn feasts.” If the French Opera House was an apt symbol for the grid, the asymmetric Live Oaks serve as a symbol for Congo Square. The biologist Janine Benyus, author of Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, points out that Live Oaks’ spreading roots form a deep network connecting one tree to the next, holding the extended tree family together, an apt metaphor for the city itself (and something the grid ignores). “Their roots,” writes journalist Roberta Gratz, author of We’re Still Here You Bastards: How the People of New Orleans Rebuilt Their City, “spread wide but stay firmly connected to the thick, gnarled parental trunk, lending strength and balance to the branches above.”

Follow that rational axis, then, and you come to a world where reason has some competition, majestic trees that evoke metaphors and Native American and African legacies that privilege knowing and engaging the world and creating community differently. Here, Descartes’s quest for certainty has no role. Such alternative traditions honor and embrace knowing not through “reason’s click-clack,” as poet Wallace Stevens dismissively calls it, associating it with the sound of the machine age that reason will give birth to, but rather through performance, ritual, and myth. According to many Native American traditions—Trickster myths about Coyote or Anansi—knowing in the rational way is the enemy; the pursuit of being right, certain, can trap you.

Shifting locales for a moment to underscore the native distrust of reason, Black Elk, a heyoka or Trickster of the Oglala Lakota people, having been forcibly removed from their native lands and resettled, lamented the utilitarian, log houses they were given:

… we made these little gray houses of logs that you see, and they are square. It is a bad way to live, for there can be no power in a square. You have noticed that everything an Indian does is in a circle, and that is because the Power of the World always works in circles, and everything tries to be round. In the old days when we were a strong and happy people, all our power came to us from the sacred hoop of the nation, and so long as the hoop was unbroken, the people flourished.

These metaphors that link patterns to spiritual forces do not present themselves as scientifically certain. The question of certainty doesn’t arise. Nonetheless, they are presented with the authority of having been subjectively experienced: “You have noticed … everything tries to be round. … there is no power in a square.” Knowing through performance, ritual, and myth—seeing hoops and circles everywhere—both embraces you in tradition and frees you: “the people flourished.”

Perhaps there is something more to learn from the circles in Place Congo. Congo Square was an informal space the city planners did not lay out. Hence, improvised. There, circles organically formed according to tribal background for call-and-response drumming, chanting, and dancing. Though rivalries among tribes of origin were felt, a community emerged that crossed tribal boundaries that never would have been broached in Africa.

If the grid represented an orderly, rule-bound world, Place Congo was “a realm of community, freedom, equality, and abundance.” These words, by Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin, come from his description of Renaissance carnival culture, which later morphed into New Orleans Mardi Gras. So it’s wrong to think that nonrational ways of knowing were historically only nonwhite. European traditional cultures also honored such nonrational ways of knowing. During carnival, the wheel, or circle, of fortune turns—untouched by an intentional hand—and the king becomes fool and the fool becomes king. On Mardi Gras Day, foolish ways of knowing have their day.

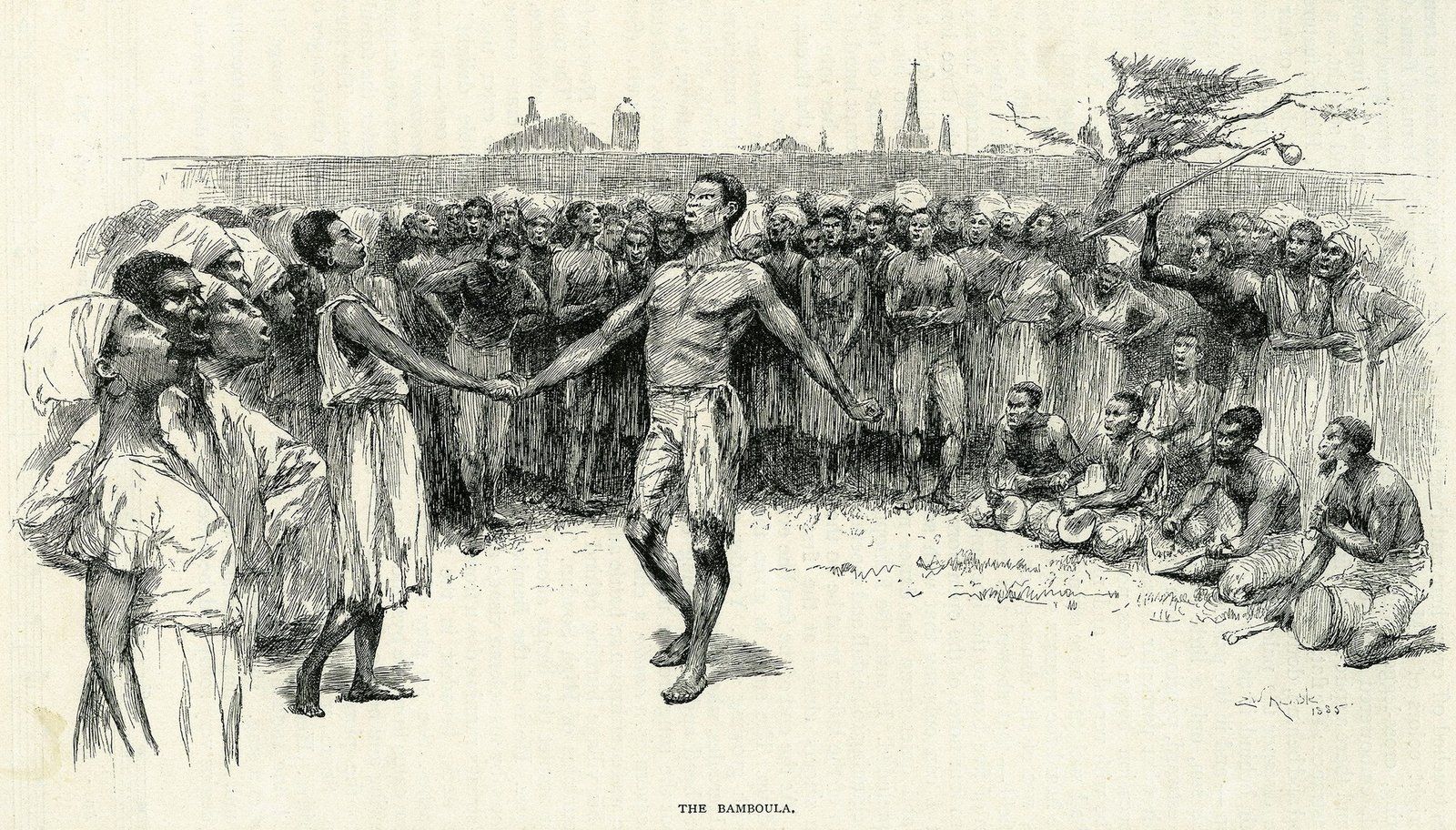

In New Orleans, the axis ran from the grid’s squares to Congo Square’s circles, from power to something like freedom. Place Congo was a lively place, especially on Sundays. Under the French Code Noir (1685/1724), as under the Código Negro when the Spanish took over in 1768, enslaved people enjoyed their Sundays after church service and until sunset, free of the backbreaking, soul-crushing, genocidal business that was slavery. Uniquely in North America, under the French and Spanish codes they were allowed to use their native instruments. Drums and horns were outlawed in the Protestant colonies for fear of their use to muster slave revolts. In New Orleans alone, though such revolts were feared, the enslaved were free to express African legacies at the center of which was and is the Bamboula, a circular rhythm and circular dance.

While in New Orleans to engineer our waterworks, Benjamin Latrobe, the designer of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., and “father of American architecture,” stumbled on the Bamboula circles at Place Congo. As he approached Back a’ Town, on the far side of the grid where blocks had been platted but were largely still unimproved, he heard what sounded like horses trampling a wooden floor. When he reached Place Congo he found “5 or 600 persons assembled in an open space or public square.” (According to historian Freddi Evans, Latrobe’s visit fell in February, the city’s coldest month, and that in better weather gatherings in the thousands were reported.) All “engaged in the business seemed to be blacks”—he “did not observe a dozen yellow [i.e., mixed race] faces.” He found not a single mass but rough circles “the largest not ten feet in diameter.” As Congo Square historian Jerah Johnson remarks, “Never had Latrobe seen anything more brutally savage.”

You can almost hear Kurtz’s voice prefigured from deep in the heart of darkness.

Call and Response as “Signifying”

Such music not only retained African modalities that prefigure jazz, it also anticipated the central trope, according to Henry Louis Gates, of African American discourse, signifying. To signify—an African American concept and phenomenon that can help illuminate the deep structure of improvisation—is to obey the social order or norms, but in a way that slyly undermines their power.

When, for example, a 1786 sumptuary law forced women of color to wear head coverings, they “signified” on the law by wearing tignons, elaborate headdresses fashioned in luxurious cloth. Historian Virginia Gould notes that the law was meant to control women “who had become too light skinned or who dressed too elegantly, or who, in reality, competed too freely with white women for status and thus threatened the social order.” The sumptuary laws envisioned head coverings that fit their low status. Fat chance.

Displaying a regal air and the creativity of their wearers, their elaborate tignons obeyed the law while making nonsense of its purpose and point: You say I need to cover my head? OK, watch this.

At its simplest, signifying means to say one thing and mean another. Irony. A flexible trope, it is a way of appearing to say yes while in fact saying no. It’s a response that cunningly marks an expressive, often disruptive difference from the call. As Yale’s expert on African art and culture Robert Farris Thompson writes, the music of African retention was made of “songs and dances of social allusion (music which, however danceable and ‘swinging,’ remorselessly contrasts social imperfections against implied criteria for perfect living).” Call and response goes to the very heart of the notion of good government, of popular response to the ideal leader: You say this, and I say it’s that. How do we move forward. The community the Bamboula circles expressed and created was, we can suppose, an unspoken commentary on the imperfections of the grid-bound community across Rampart Street. The colonists, though in the first generations largely made up of the dregs of French society, used reason and logic to declare the enslaved not fully human even while the music and dancing in Place Congo articulated their humanity well-enough to impress the father of American architecture. Call and response.

Improvisation always carries an epistemological charge: improvisers seek to enlarge rationality, and hence their humanity, by incorporating some element that reason had dismissed as beneath rationality. Blacks were dehumanized by white Creole culture with the charge that they were not only irrational but subhuman. The proof? They couldn’t read. Why? Because it was illegal to teach them to read. The logic that supported the superior rationality of white Creole culture was full of holes and surely would not have held up in a court of law. But the problem Blacks faced was that they were also by law not allowed to give testimony. The only way forward was to go around, through signifying to demonstrate their humanity. If the grid culture wouldn’t acknowledge their humanity, at least in Congo Square and in acts of signifying they could experience it for themselves.

On Terry Gross’ Fresh Air program in 2018, New Orleans pianist Jonathan Batiste played one of Bach’s “Two Part Inventions” and then reflected on its union of simplicity and complexity:

But it’s just two voices. You see … the simplicity of how he makes something that is just two melodies playing in conversation, asking questions, responding, sometimes they’re talking at the same time. Other times, it’s call and response. Sometimes it’s in harmony. Sometimes there’s dissonance. Just … that’s life. That’s our journey exemplified in a simple piece that he wrote for his kids. That’s amazing.

There is something very fundamental in call and response. It is the root of all innovation if not all art. Innovation always comes about in response to some need. Something’s wrong. How can we build upon it to make it better? Building community, improvisation’s yes…and gives voice to both our individuality and our shared humanity.

Yes, the map with its axis that runs from force to empowerment is just a metaphor, a subjective creation, like Black Elk’s circles and squares. But it captures not only the transgressive quality of improvisation, but also the inevitability we feel that jazz as we know it would first bubble up from such swampy soil. As the late jazz pianist and educator Ellis Marsalis (father of several prominent jazz musicians) used to say, “In other places, culture comes down from on high. In New Orleans, it bubbles up from the streets.”

Create a fixed, rule-bound, inflexible order and you can be sure that a longing for freedom with a taste of chaos will come calling. Almost like a natural, chthonic force that rises from the earth or from the soul when men in their quest for certainty get a little too orderly, disorder is sure to emerge to challenge that order. To the intuitive mind, an ordered world has always left something important out. The history of improvisation since antiquity bears this out. Improvisation is the site of a perennial battle between reason and unreason, a battle out of which cultural innovation has flowed. It is Joseph Campbell’s hero’s quest: uncomfortable with the cultural stasis around her, the hero hears a call to venture into the unknown.

The French Quarter’s hyperrational grid and what happened beyond its boundaries in Congo Square is a metaphor for improvisation: art that pushes back against rule-bound, closed-form, rigid culture in favor of unruly, open-form, fluid freedom. That pushback reflects the battle between the rational and intuitive, the intuitive mind’s effort to regain its voice from the undue silencing by reason that neuroscientists are now exposing.

The metaphor of grid and Congo Square’s circles captures the confrontation, the pull and tug and pushback that is at the heart of improv. “A map is not the territory it represents,” scientist and philosopher Alfred Korzybski argued, “but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness.” The usefulness of this cognitive map is that it calls attention to the structured battle at the heart of improvisation. Call and response.

E.g., The Battle Over the New York Grid

That conflict is echoed more than a century and a half later in Greenwich Village’s great lionizer and defender, Jane Jacobs, who wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities in the early 1960s, just at the moment scientists across disciplines were beginning to discover how in nature “strange attractors” sometimes self-organize turbulence into a new order. She celebrates the “organized complexity” of the city streets of her grid-free Greenwich Village, “the daily ballet of Hudson Street,” her home.

For Jacobs, conventional modern city planning mistook cities “as problems of simplicity and of disorganized complexity,” which, because irrational in nature, need only a good helping of Apollonian rationality to solve. The Radiant City of the French architect Le Corbusier got rid of all that irrationality with high density towers and adjacent parks. For Jacobs, Louis Mumford’s urbanist vision, The Culture of Cities, was largely “a morbid and biased catalog of ills.” His “Decentrist” solution, enabled by President Eisenhower’s interstates and Robert Moses’ parkways, was the Garden City, the automobile-enabled and suburban low-density tract homes. Wedding these two urban visions, the “Radiant Garden City Beautiful”—Jacobs’ term for the compromise between Le Corbusier and the Decentrists—gave rational impetus to the Apollonian rage for urban renewal that did so much, especially in Robert Moses hands, to decimate the city and ruin the lives of many poor residents.

For Jacobs, the “strange attractor” that made New York City—or at least her grid-free Greenwich Village—not only livable but full of vitality was simple: “eyes on the streets.” That is, given enough density, urban streets promised enough observers to keep streets safe. Chaos theory, which began to emerge in diverse sciences in the early 1960s, discovered ways to describe how order spontaneously emerged because of a strange attractor from chaos or turbulence. The lack of eyes on the streets and in the parks that surrounded the Corbusian high rises and the pedestrian-free suburban tract developments explained their deep human failures. According to Jacobs, “the humane and

almost unconscious assumption of general street support when the chips are down—when a citizen has to choose, for instance, whether he will take responsibility, or abdicate it, in combating barbarism or protecting strangers. There is a short word for this assumption of support: trust. The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts.”

That trust—another of Jacobs’s strange attractors—is unthinkable if you conceive the city as “a morbid and biased catalog of ills.” Without trust, how does community emerge?

New Orleans was not the first nor the last grid city. In 1807, the New York State Legislature appointed a commission to provide for the orderly development of Manhattan between 14th Street—above Jacobs’s beloved Greenwich Village—and Washington Heights. The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 instituted the grid loved today by developers and hated by naturalists like Frederick Law Olmsted and urbanists as diverse as Mumford and his opponent Jacobs.

One of the grid’s most colorful opponents is Timothy “Speed” Levitch, a former tour guide for New York’s Grey Line bus tours, once described as “a psycho-geographer for the unloved, the unseen.” In Bennett Miller’s 1998 documentary, The Cruise, available on various streaming sites, Levitch contrasts “anti-cruising,” or what he thinks of as “commuter consciousness,” with his vision of improvisational city living: “cruising.”

This contrast comes to a climax in the film on a walk from 34th Street toward 23rd Street, deep in the grid. Levitch notices a homeless person’s bedding on the street and recalls a conversation he had with a “fastidious” woman, clearly an anti-cruiser, about the grid above 14th Street. She believes “everyone likes the grid plan.” But to Levitch, “the grid plan is puritan, it’s homogenizing, in a city where there is no homogenization available, there is only total existence, total cacophony, a total flowing of human ethnicities and tribes and beings and gradations of awareness and consciousness and cruising.” Levitch could be describing Congo Square. He tells us that this fastidious woman’s remark, “everyone likes the grid,” seems not to include “whoever that is under the white comforter, cuddled up on 34th and Broadway.” Nor, he notes, does it include Levitch himself, her interlocutor. Suddenly Levitch is not a person but a thing.

With no place on the grid to call home, both are dehumanized, othered. Imagining what that homeless person thinks about the grid plan, Levitch waxes visionary. Responding to the grid plan’s call, he imagines that the homeless person is, “probably much more on my plane of thinking, […] which is, let’s just blow up the grid plan and rewrite the streets to be much more a self-portraiture of our personal struggles, rather than some real estate broker’s wet dream from 1807.”

For Levitch, “the fastidious lady … being so completely allegiant to the grid plan” buys into normative civilization as it is. She “can’t imagine altering this civilization … this meek and lying morality that rules our lives … can’t imagine standing up on a chair in the room to change perspective … can’t imagine changing my mind on anything … can’t imagine changing my own identity that contradicts other identities.” Willing to “just blow up the grid plan and rewrite the streets to be much more a self-portraiture of our personal struggles,” Levitch embraces chaos.

Hardly a solution to appeal to urbanists, the impulse to chaos, to freedom must somehow be given a hearing. The first step surely is to recognize that the counter-impulse, to control and to rational order, is deeply inscribed in urbanist methodologies. The technologies that make building possible, the bread and butter of urbanism—the iPhone, AUTOCAD, and AI—speak loudest and rule the roost. Even so, “the still, sad music of humanity”—like that heard on Congo Square or on New York City’s grid—will continue to demand a hearing.

Improvisation—art that claims to be composed in the moment of composition, often in unruly fashion—has been fighting the fight against hyper-rationalism since antiquity. Improvisation is one of the sites, like Place Congo, like Greenwich Village, where that battle has always been, and continues to be, fought. Improvisation—across media and discourses, including urban planning—challenges the privileging of reason in our quest to determine how best to know the world.