Lost Masterpieces: 6 Iconic Buildings That Met the Wrecking Ball

Judging for the 11th A+Awards is now underway! While awaiting the Winners, learn more about Architizer’s Vision Awards. The Main Entry Deadline on June 9th is fast approaching. Start your entry today >

The public court of opinion is a beast that moves in ebbs and flows, and architecture has long been one of its choice topics of debate. Aesthetics fall in and out of favor, and correspondingly, buildings rise and fall. Brutalism flourished in the 1950s, only to be derided and demonized mere decades later, before its surprise revival in the 2010s. And who can forget Donald Trump’s 2020 executive order aligning “beautiful” federal buildings strictly with classical and traditional styles of architecture?

This reductive checkbox exercise of designating schools of design as good or bad is deeply harmful. It risks homogenizing our skylines and disregards the significance of the historic built landscape. Over the centuries, scores of celebrated structures have met the wrecking ball in the name of redevelopment, profit or whim. Thankfully, many architects and urban planners today recognize the importance of adaptive reuse initiatives, which impart fresh purpose to existing buildings while protecting their fabric. But history hasn’t always been so kind. Let’s rediscover six lost masterpieces that were turned to dust…

Pennsylvania Station

By McKim, Mead & White, New York City, New York

Photo by: Detroit Publishing Company, Pennsylvania Station aerial view, 1910s, public domain

Photo by: Cervin Robinson creator QS:P170,Q18511598 – Photographer, NYP LOC5, public domain

A Beaux-Arts behemoth, the original Pennsylvania Station in New York City once sprawled over two whole city blocks — at its opening in 1910, The New York Times deemed it the “largest building in the world ever built at one time”. This historic gateway to the Big Apple offered an immersive spatial experience for travelers. The general waiting room evoked the grandeur of Ancient Rome with its classical columns, travertine floors and soaring coffered ceiling. Meanwhile, the main concourse was crowned with a spectacular vaulted glass roof framed by ornate steelwork.

However, as rail travel declined in the 1960s in favor of cars and airplanes, so too did the station’s fortunes. Despite preservation campaigns and protests, the structure’s owners, the Pennsylvania Railroad, embarked on a three-year demolition plan in 1963 and rented out the air rights to the site. Erected in its place was Madison Square Garden. Sculptures and columns from the razed terminal building have since found new homes in the Brooklyn Museum’s Steinberg Family Sculpture Garden.

Nakagin Capsule Tower

By Kisho Kurokawa, Tokyo, Japan

Constructed in 1972, Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo’s Ginza district was one of the world’s most radical housing blocks. Its futuristic form epitomized the values of Japan’s Metabolist movement, which reimagined the built environment as a living entity that could grow and adapt to meet the demands of future generations. In keeping with this philosophy, 140 capsule units were bolted onto the tower’s two central spines, each stacked at differing angles. The capsules, which housed self-contained tiny homes, could be replaced in the future when the need arose, renewed like the cells of an organism.

Sadly, this early dream of sustainable housing was never fully realized. Over time, many of the capsules fell into disrepair and were abandoned. To make matters worse, there were health concerns over the large quantities of asbestos used in its construction. While a developer was sought to fund the structure’s restoration, the appeal was unsuccessful. In April 2022, the tower was dismantled and demolished, after owners and the management company agreed to sell the plot the tower stood on. Glimmers of Kisho Kurokawa’s grand vision still live on and a number of the capsules have been saved and donated to museums or repurposed as rental units.

Hall of Nations

By Raj Rewal, New Delhi, India

Defined by its tessellated triangular skin and capped pyramid form, New Delhi’s Hall of Nations was opened in 1972 to mark 25 years of India’s independence. A symbol of the country’s post-colonial history, the striking modern landmark, designed by acclaimed Indian architect Raj Rewal, was the world’s largest concrete space-frame structure at the time. The vast 72,000-square-foot exhibition hall was void of columns and its geometric concrete frame was cast in situ.

In 2017, the Indian Trade Promotion Organisation revealed plans to demolish the Hall of Nations and a number of other event spaces to make way for a new convention center, a shocking move that was strongly criticized by architects and historians across India. Rewal, the building’s architect, petitioned the court to step in and recognize the hall’s national importance. However, his appeal was rejected on the grounds that the building was too young to qualify for heritage status. Just days later, the Hall of Nations was reduced to rubble on 24 April 2017.

Maison du Peuple

By Victor Horta, Brussels, Belgium

An unusual collision of socialism and ornate design, Maisons du Peuple, or houses of the people, sprung up across Belgium towards the end of the 19th century. Commissioned by the Belgian Workers’ Party, they were community meeting spaces for the country’s working classes and their largest center in Brussels was the pièce de resistance.

Designed by Victor Horta, it was one of Belgium’s most important Art Nouveau buildings and a masterful fusion of ideology and architecture. Combining flowing, elegant lines, including Horta’s signature whiplash curve, with innovative materials such as iron and glass, the structure negotiated a careful dance between estheticism and industrialism. Inside, intricate iron beams laced the ceiling of the top-floor auditorium and ribbons of clerestory windows allowed natural light to pour into the building.

The 1960s heralded a destructive spate of urban development in Brussels, from which the neologism Brusselization was coined. Large swaths of the city’s historic landscape were erased and Maison du Peuple was sadly one of the casualties. Despite protests from more than 700 architects worldwide, the building was demolished in 1965 and replaced with a 26-story skyscraper.

Prentice Women’s Hospital

By Bertrand Goldberg, Chicago, Illinois

The distinctive four-leaf clover plan of the original Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago signified a dramatic departure from conventional typology. Bertrand Goldberg’s revolutionary Brutalist design for the maternity unit sought to redefine patient care. Offering direct sightlines to patients, nurses’ stations were situated in the core of the tower on each floor, with wards radiating out from the center.

While the structure’s spatial organization was pioneering, the curvilinear concrete form was cutting-edge in its construction too. A first for the architecture industry, specialist 3D-modeling software known as finite element analysis, previously only used in aeronautics, was employed to design the interlocking arches at the base of the cantilevering tower. Yet despite its architectural value, the nail in the hospital’s coffin came in 2013 when plans were finalized for the construction of a new biomedical research center on the site. Preservationists fought to protect the building, even garnering support from the likes of Frank Gehry, but to no avail. The hospital’s demolition was completed in 2014.

The Imperial Hotel

By Frank Lloyd Wright, Tokyo, Japan

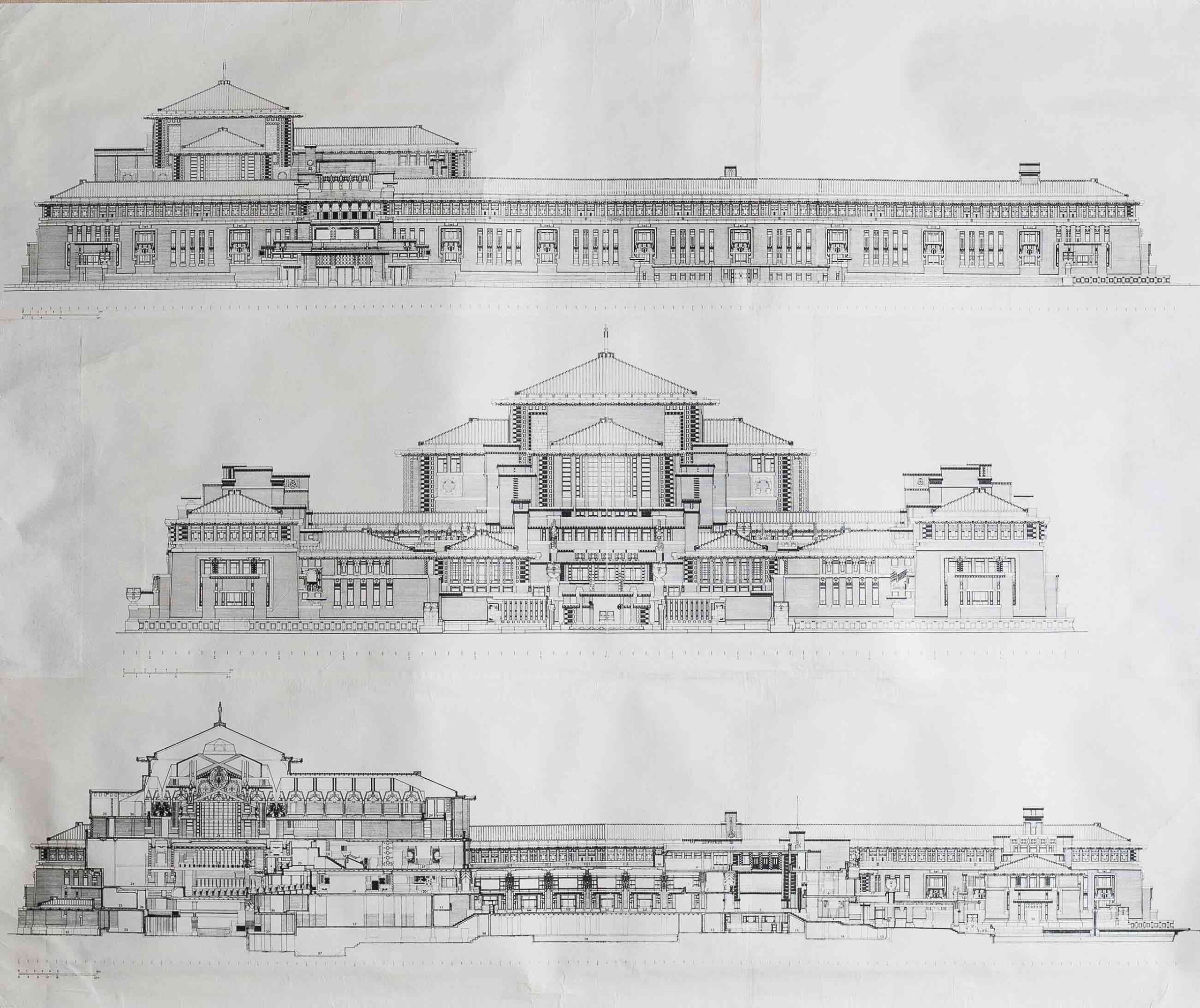

Image by: Unknown author, Imperial Hotel Wright House, public domain

Image by: Frank Lloyd Wright, Imperial-Hotel-Tokyo-Plans-Design-Frank-Lloyd-Wright, public domain

Frank Lloyd Wright’s most famous building in Asia, the 25-room Imperial Hotel was built on the bones of a previous iteration by Yuzuru Watanabe. Wright’s design was one of the earliest examples of Mayan Revival architecture — the lobby’s intricate stepped lines referenced the forms of the Mesoamerican pyramids, while the exterior was clad in hand-scratched brick, volcanic Ōya stone and ornamental glass inlaid with gold. A tranquil reflecting pool sat at the heart of the hotel, lined on either side by accommodation wings.

In an unfortunate coincidence of events, the hotel opened on 1 September 1923, the very same day that the Great Kantō Earthquake struck Japan. It devastated Tokyo and the surrounding regions, yet Wright’s masterpiece endured. Some put its survival down to the hotel’s above-ground foundations, which were intended to float on mud and cushion seismic tremors. The building would go on to bear the brunt of the American bombing of Tokyo in the Second World War, only to be razed to the ground in 1976 and replaced by a modern high-rise.

Judging for the 11th A+Awards is now underway! While awaiting the Winners, learn more about Architizer’s Vision Awards. The Main Entry Deadline on June 9th is fast approaching. Start your entry today >