living in THE LINE: explore daily life in saudi arabia’s future vertical city

discovering a new urbanism with ‘the line’

The team at NEOM has already begun construction on Saudi Arabia‘s ‘zero-gravity’ city THE LINE. The group is reimagining how a city is built, and what sort of life is possible within its mirrored walls. The colossal scale of the proposal has never been seen and its concentrated proportions unheard-of. THE LINE is a rejection of the sprawling suburb and a hyper-exaggeration of the supertall skyscraper. Often referred to as a ‘groundscraper,’ the singular structure will stretch 170 kilometers — over one hundred miles — to house a city of nine million people.

The proposal dramatically rethinks the built environment’s relationship with the natural environment, claiming the car-free place will be powered by 100 percent renewable energy and will operate at net-zero. What’s more, it proposes an entirely alien way of life, with its occupants living along a stark boundary between the hyper-dense city and a wild, untouched desert.

To put the scale of THE LINE into perspective, it would take over an hour — perhaps nearly two hours — to drive that length by car. The team at NEOM claims that with its system of high-speed transport, one could reach end-to-end in no more than twenty minutes. Tall and narrow, the city will be 500 meters above sea level and 200 meters wide. (1,640 feet high and 650 feet wide). That’s taller still than the 102-story Empire State Building and its spire.

The project is reinventing urbanism, seeking to remove the pollution, noise, and sprawl of city living in favor of an ultra-efficient utopia. In an exclusive interview with NEOM’s director of urban planning Tarek Qaddumi, designboom explores how the megacity will operate, and what life inside THE LINE will look like.

‘there is no hierarchy whatsoever‘ | images courtesy NEOM

‘there is no hierarchy whatsoever‘ | images courtesy NEOM

‘everything is everywhere’

designboom (DB): How will programming be distributed vertically throughout THE LINE? Will housing be spread across all levels? What do you expect would be the differences between the environments of the lowest levels and those toward the top?

Tarek Qaddumi (TQ): THE LINE. Besides it having this linear quality that connects the different regions of NEOM, and intends to preserve 95% of the territory, is a three dimensional city. This means that it is stacked vertically. You don’t have a city that is flat, where every little building has a plot. One would wonder why we’d do that. For one, we turned the footprint of the city from what is 1,600 square kilometers of London, to 34 square kilometers of THE LINE.

The whole world could easily shrink to occupy so much less footprint on the earth, and allow the deserts to be deserts and Amazons to be Amazons. That’s where the idea started. If you have different layers of the city stacked at height, you have New York, then you have Paris, then you have Copenhagen. In five minutes, instead of being able to access 22,000 people, you can access 80,000. That changes everything. This proximity allows you to access, instead of a family clinic, a hospital that serves 80,000 people within a five minute walk. Also pharmacies, several schools, potentially higher education institutes, and so on. Of course all your neighbors are very close to you. This we call hyper-proximity.

In terms of organization, we say that on THE LINE ‘everything is everywhere.’ This hyper-mixed-use means that there will not be an ‘office district’ or a ‘government district.’ Instead there will be a constant mix of commercial, residential, university, even manufacturing, all happening at the same time. That allows a more dynamic, more interactive, and more diverse community.

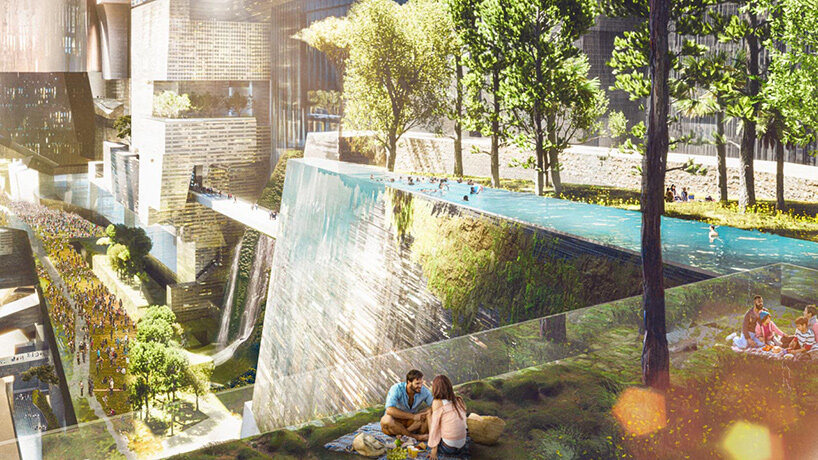

Of course, there’s no such thing as ‘hierarchy of height.’ At times, the lowest levels will be attractive for people to have that direct access to nature. At other times, the levels at 300-meters up will be ideal for the view. And of course, some will just want to be on the top. But with that, there’s a distribution of social housing, retail, and commercial that happens all across — there is no hierarchy whatsoever.

DB: What are the challenges of ensuring that the lowest levels or the middle levels receive natural sunlight and fresh air? Will the facade be permeable?

TQ: The facade is actually vision glass. It’s no different than actual glass except that on the outside, it will have a reflective quality that will help to shade the inside. Remember, we’re in a hot part of the world. It will also have enough opening to allow air to come through — particularly through the lower parts — and filter through to create a ventilated heat stack effect that is constantly cooling the city, not just the building.

The choreography of masses and buildings at height will filter the light just right to get the right amount of southern light. That brings a bit of heat and warm light with it, and the right amount of northern light as well. Both the north and south facade allow all the light that you want. We’re actually working on holding some back. You crack your curtain here and strong light comes in. How do we temper that light? How do we play with it? How do we balance light and shade to have an enjoyable public realm?

‘we have landscaping at height with enough light to come in from the sides‘

landscape and preservation in saudi arabia

DB: The proposals suggest landscaped areas throughout. What is your strategy for introducing green space?

TQ: Public realm is just as important to a city as its buildings. The differences between a building complex and a city is its public realm — its plazas, its parks, its pedestrian walkways, its alleys, its paths and so on. Here, the only difference is that we have a city that’s without cars and without sidewalks. Everything is pedestrian. We have mobility at height that will take you further down if you wanted to. But in essence, it’s a combination of buildings and open space. Some of this open space will be landscaped. We have landscaping at height with enough light to come in from the sides.

We think of landscape as a philosophy. If you think of a Japanese zen garden, it talks about the philosophy of a way of life. If you think of a perennial, seasonal English garden, it talks about a way of life as well. When we think of NEOM, we think that the garden itself should also reflect NEOM’s values of nature preservation, and almost going out of the way to rehabilitate.

A lot of nature today is suffering. Even what we think of as pristine isn’t. The North and South Poles are suffering, so you could imagine the rest of the world. We think of nature as a little bit of prosthetics and a little bit as artificial devices that sequester carbon. We’re looking at a landscape with not just a pure romantic view of nature, but also something that could be more impactful toward what our environment should be.

‘a lot of nature today is suffering‘

‘a lot of nature today is suffering‘

near and far: moving throughout the line

DB: Can you explain plans for transportation? Are there different methods of moving short distances versus long distances, and horizontally verses vertically? Could one travel upward two levels on foot, or would an autonomous vehicle taxi residents short vertical distances?

TQ: First let’s tackle the walking side of things. This is by far a walking city. Again, within five minutes in London, 16,000 people, in Manhattan 22,000 people — here, you would access 80,000. In a fifteen-minute walk, you’ve already covered quite a bit of population and place.

However, if traveling ten kilometers down, certain levels will have either group mass transit (GMTs), or individual pods. Say a couple is dressed for a party and doesn’t want to take mass transit — they could take an autonomous vehicle and have a private ride. But there’s no ownership. A group of these pods could take as much as eight people up to ten kilometers down the LINE at height.

The city is 170 kilometers long. Let’s say you are at the 40 mark, and you want to get to the airport at the 150 mark. You will go down to a station connecting to a high speed system which will zip you up to the airport. Since we’re talking about airports, you would not worry about your luggage. Luggage will be picked up and delivered. You wouldn’t worry about getting to the airport, or even through security or immigration. It’s all biometric. You just walk out of your city onto the plane.

‘This is for people to enjoy as much as it is for preservation‘

‘This is for people to enjoy as much as it is for preservation‘

going outside

DB: You mentioned access to the surroundings. How would a resident, say, visit the beach? Will there be transportation outside the LINE should they want to explore nature? Or are people are disconnected from the landscape, viewing it instead of occupying it?

TQ: We see all that we have preserved as an opportunity, one, for animals. We’re looking at a whole re-wilding program for what had lived there in ancient times — leopards, cheetahs, dogs — whatever used to be here, we will bring it back. We think that there is room for us to re-introduce what was and to co-inhabit this earth again together. We also did a survey of plants that had suffered from over grazing. We will bring back all of that flora — with a drop of water you can do a lot.

This nature would be accessible to people and animals all together. This is for people to enjoy as much as it is for preservation. You would either go to the top of the building where there are eVTOLs, or autonomous copters of sorts — there is already a joint venture between NEOM and companies in this field. These would take you out to different parts of nature.

Or you would go to the bottom where there are autonomous electric vehicles which will take you out. Some of them would even be an enjoyable experience in themselves. There are glass bubbles, maybe you are buckled up around a table where there is no driver, and you’re just enjoying the ride.

The beaches and the mountains are something that we enjoy here. There’s the beautiful coast of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba with its incredible coral that we can see when snorkeling or diving. Then there’s the middle, with the Precambrian mountains. It’s the Arabian shield that goes all the way down to the peninsula. Then the upper valley is more of a Martian landscape.

DB: You mentioned renewable energy. Can you describe the strategies of powering the line?

TQ: The base of NEOM is a zero emissions region. So no pollution whatsoever, no carbon dioxide whatsoever. To power all of NEOM we have three strategies — solar energy, wind energy, and hydrogen — all working in combination for different cycles of day and night and with better storage. Basically, it’s all renewable, we don’t depend at all on fossil fuel.

‘whatever used to be here, we will bring it back‘

‘whatever used to be here, we will bring it back‘

cleaner, quieter, closer

DB: How would you describe the benefits of a vertical city to someone who values rural living?

TQ: I always say if it’s not more beautiful than Florence, then why are we doing it? Then let’s just repeat what we know. On hot days, you’re going to enjoy the fact that the city is almost shaded by itself. You’re going to be walking in places that are breezy and self-shading. It’s a microclimate that works really well for this environment.

There is also the equity of view. Everybody has a view out. Take Florence — most people live between the stones of Florence, but some have villas with beautiful gardens and the Tuscan landscape beyond. Here, everybody has that view of the mountains and the sea. When looking out, you won’t even see other buildings. You own that perfect view.

Finally, the availability of services. Like I said, the capacity in a city to walk to the best hospital, the best galleries, a selection of retail. We know that online shopping is taking over, so retail is going to be more experiential.

Imagine a place without the noise of cars, the smog, the traffic lights. There’s never going to be a traffic jam. We look at some of the some of the renderings that we put together with our architects, and they almost look fake, like: that’s all park — where’s the road? It doesn’t have roads and still functions.

DB: You mentioned flying vehicles, or eVTOLs — how will this traffic be organized?

TQ: These will be to go out to the landscape to explore. They’ll be complemented by movement on the ground. So I don’t know that there will be traffic. A lot of people are just going to live in the city, take Manhattan for example. A lot of people are walking and taking pods every now and then to move around the city, but it’s going to be a city without traffic jams and without lost time. We often say that time is something that is more precious than anything else. Here, your school will be less than a five minutes walk, whether it’s high school or elementary school. Work can be no more than twenty minutes away because you’ll be able to reach end to end in twenty minutes.

DB: Can you describe how the LINE will receive water?

TQ: We don’t have a lot of water. We depend on desalination from the sea, so we take water and we extract the salt. One of the traditional issues with desalination is the fact that you’re left with brine, a high concentration of salt, and it is dumped back into the sea which becomes more and more saline with time.

We have a zero brine discharge policy. This means that once we extract pure water out of the sea water, what is left is converted into industrial uses. We’re looking at creating blocks out of salt for building material. For us, salt is a commodity that we will use and we will not discharge back. Then water is pumped across the LINE, and there is a whole sequence of reusing and recycling.

‘we extract pure water out of the sea water… there is a whole sequence of reusing and recycling‘

‘we extract pure water out of the sea water… there is a whole sequence of reusing and recycling‘

the structure: building saudi arabia’s city of the future

DB: The project has been described as ‘zero-gravity,’ while early diagrams and animations suggest floating volumes. Can you describe some of the unique structural challenges of a vertical city? Are there already plans toward approaching or resolving these ambitious floating structures?

TQ: We’re working with a lot of world class architects. Each one of them is working with the engineering firms, whether structural, utility, sustainability, and futurology. As a concept, we like the idea of zero gravity, of floating, of things being able to be where they need to be relative to everything else. In many respects these have been solved structurally, unless they are completely suspended in space, then excuse the rendering. But for a lot of them, these are proposals that have been studied structurally and vetted. We are reimagining what a city looks like, for sure.

DB: Most ambitious projects undergo major changes between early concept to completion. How do you predict the design will change between early visualizations and the completed construction?

TQ: We’re constantly studying. And we realize that while you’re inventing something and trying to build it at the same time, you’re racing against time. We’re turning every stone and looking for every new opportunity to be more sustainable, more livable, to take advantage of what we’ve constructed for ourselves, and to find the best technologies. In terms of life inside the LINE, we imagined it pretty well. We’re even working with universities to quantify walkability and livability through computer systems.

We are developing the design into something that can be built in a way that is more industrial, and more rational than normal contracting practices. It’s not going to be brick and mortar, plaster and paint. Things are going to arrive in pieces, readymade blocks, and flat packs. We’ll work more in how the car industry has been industrialized, with a kit of parts that’s assembled.

As you can imagine, that influences the design. We’re going back to our designs, trying to rationalize instead of having 5,000 door sizes, we’re happy with 100. That doesn’t mean that we’re going to be limited to one door size, but even 100 door sizes is more than enough. It will give us enough numbers in order to industrialize that process. And that’s going to help us save time and effort. We also believe that through an industrialized process, we’re going to reduce a lot of waste in the construction process that goes up to 30% at times.

‘these are proposals that have been studied structurally and vetted‘

racing against time

DB: What is the status of the construction?

TQ: Back in 2021, we started the construction of the spine, which is the infrastructure corridor that runs the whole length of THE LINE. And in April of this year, we started the piling foundations of the first modules of the LINE.

DB: And THE LINE will complete in eight years — by 2030?

TQ: We are looking at an aggressive schedule, and the first modules will be completed before that. However, the first substantial population living on THE LINE will be in 2030.

DB: So the project will be able to grow over time.

TQ: Absolutely. The first substantial population we are looking at is about a million plus one, one and a half million. But then the capacity of the line is nine million people. So you can imagine it’s a city that’s going to grow organically. Nine million people is greater London or New York with its five boroughs. So this is going to be an organic process that will take years.

DB: Any last comments?

TQ: THE LINE has become a bit of a bit of a religion. It’s become something that we all here want to see happen. The work has started, so we’re racing against time to make it livable, rational, and sustainable. We don’t want to lose opportunities. We want to make sure that we gain every advantage and reinvent everything that needs to be reinvented, whether it’s education or sports — sports will be more activity, wellbeing.

We’re going to try and bring back health into the city, we’re going to bring back joy into the city. And give people back time — instead of their being busy laboring over tedious, daily tasks — to allow more time for hobbies, for interests, for friends. To try to work on all of that together. And until then we’ll face challenges and difficulties like any other project of the size, But we have a goal in mind and a timeline and we’re on it.

project info:

project title: THE LINE

location: NEOM, Saudi Arabia

previous coverage: July 2022, January 2021