interview: australian pavilion ‘unsettles truths of colonial past’ at venice architecture biennale

‘Unsettling Queenstown’ – Australian pavilion at venice biennale

The Australian Pavilion reveals dark truths from the persecution of First Nations people in Unsettling Queenstown at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, which runs until November 26, 2023. The pavilion exhibition examines Australia’s colonial past in a quest for discovery about the history of the country’s indigenous population, rather than accepting the spun tales that have been passed down by imperialists. Through first-hand research and interviews, the project team displays their findings through multiple mediums, including films, a skeletal copper structure of ‘The Empire Hotel‘ in Queenstown Tasmania, and an ‘open archive’ spread across the wall.

‘The sculpture is a ghost, remnant of colonialism. You circulate through this space, look at these big films, and then you can turn around and look out through this Belvedere. We look back through these big arches and reflect on the material that we’ve gathered from Australian architects about their tactics around decolonization,’ curator Anthony Coupe tells designboom in an introduction to the space. During our visit, we had the privilege of meeting Coupe, as well as Emily Paech and Ali Gumillya Baker of the pavilion’s five curators, and discussing the Australian contribution to this year’s Architecture Biennale.

Australian Pavilion reveals the dark truths on the persecution of First Nations people | all images by Tom Roe (unless stated otherwise)

Tackling timely themes AT THE VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE

The Australian Pavilion‘s choice of exploring the theme of decolonization can reveal dark information, but the team of curators believe it is very important, particularly now. Anthony Coupe, Ali Gumillya Baker, Julian Worrall, Emily Paech, and Sarah Rhodes present visitors with 65 ‘tactics’ in which architects can better understand how to reflect on decolonization within their own practices and frameworks. All of this comes at a time when Australia’s First Nations community seeks representation in the Australian constitution, in which they currently are not recognized.

‘When the Empire Hotel, was built in 1921, they were writing the constitution for this country. They deliberately excluded Aboriginal people in that document, which is still the national document used today. These actions have led us to still argue about how we will be included in that document, and we’re trying to have a national vote. It won’t be aboriginal people who decide the outcome, we only make up 2% of the population, so the importance in sharing this education is amplified by these current efforts to make a constitutional change,’ explains Ali Gumillya Baker on the importance of the information displaying at the Australian Pavilion. Read the interview in full below.

the exhibition examines Australia’s colonial past in a quest for discovery about the country’s history

Interview WITH THE CURATORS OF THE Australian Pavilion

designboom (DB): For our readers who aren’t familiar, can you give a description of your installation?

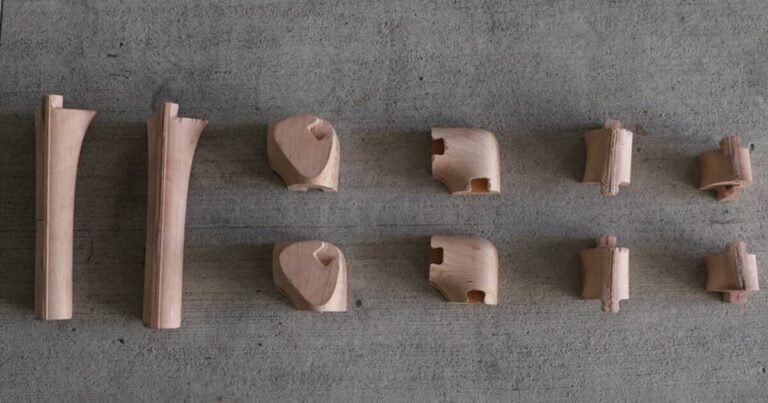

Anthony Coupe (AC): The first thing that you see when you come in is a copper sculpture. This is intended to provoke and reflect architectural origins and colonial history. The whole thing is called ‘Unsettling Queenstown’, and looks at two towns called Queenstown, one in Tasmania and the other in South Australia. There are Queenstowns all over the world, we reveal the fact that these place names reflect colonialization and ownership to a non-specific crown that is not even of place. The tension between describing place by naming and surveying compared to describing place by narrative or relationality is what we’re trying to expose.

The piece is a partial replica of the Empire Hotel in Queenstown Tasmania. To unsettle the sculpture, we decided to chop off the building at the base so it’s floating and this conjures questioning ideas of what is this thing? The gum leaves on the ground offer a sensory and spatial effect, with the skeleton structure floating above like a spaceship. The sculpture is a ghost, remnant of colonialism.

Circulating through this space you spot these big films and then you can turn around and look out through this Belvedere. We have these big imperial arches that we look back through and we reflect on the material that has been gathered by Australian architects. In the research we have on the wall, you’ll see some speculative projects, some real projects, but mainly it is a discussion of tactics, stripping away the project as a highlight. There are 65 different tactics across there which form an open archive. That’s its resonance, to create a series of specific tactics which other architects can refer to use and reflect on in their framework of decolonization.

Decolonization is a difficult thing to describe in terms of architecture, Lesley Lokko calls it ‘slippery’. While we talk about decarbonization a lot, it’s very specific and easy to measure, yet decolonization is much harder to quantify. In Australia, decolonization is not really in the lexicon of practicing architects. It’s talked a lot about in education, and we have engagement with First Nations people as part of our core framework for registered architects.

There is a third Queenstown, which is a fictional one, we call it ‘a country de-mapped’ and it takes elements of the two other Queenstowns. It again plays on this idea of land-grabbing. We have benches with headphones that are playing voices giving personal stories about the place. It is done through interviews with First Nations people, artists, and others who were live in these two Queenstowns, giveing a further reflective aspect to the exhibition. Overall, we ask questions like what’s the context? What’s your immersion into this whole thing? and then offer some glimpses of potential balances.

the pavilion displays their findings through multiple mediums | image ©designboom

DB: How did you conduct the research for the project?

Ali Gumillya Baker (AGB): As part of the process, we looked at where we live. Part of the team live in Adelaide, my family are Aboriginal from the west coast of South Australia but I’ve grown up in Gaurna country, so I interviewed a lot of my elders from Gaurna Land. We also interviewed many elders from the community of Tasmanian Aboriginals. Sarah and I asked them about how they understood the change that occurred in the environment, what they would like to see in the future, and about language and place names for these areas that are called Queenstown. We got a lot of different responses.

Sarah also interviewed non-Aboriginal people in Tasmania. Tasmania is a particularly violent site in Australia, they had a thing called the black line, where colonizers walked across the entire island of Tasmania, killing Aboriginal people and pushing everyone off of the island. It’s got quite a huge massacre history.

In the 80s, there was huge, staunch fighting amongst white population, between the loggers, the miners, and the environmentalists who were tying themselves to trees. Tasmania holds this huge tension there. Sarah interviewed some of the miners and environmentalists to talk about how they felt about the environmental degradation of Queenstown, and now that the mine is closed what is the future of the town?

We had these conversations about value of community and we sent a call out to architects across the country, asking them if and how they were thinking about decolonizing in their practice. We asked if they work with the community and what that how they understood the turning towards Aboriginal knowledge that is happening in Australia at the moment?

There’s a lot of interest in First Nations peoples, now, ten years ago I couldn’t have ever imagined. I’ve been working in universities for 23 years and there’s been a lot of racism, but the younger generation who are now starting to outnumber the baby boomers are really interested in hearing the truth, not a form of truth that is spun. They want to know what the history is properly. And so there’s a kind of immediate interest in First Nations stories and understandings, but also violence of that.