High-Tech, High Pace: This Groundbreaking Humanitarian Build Reimagines Reconstruction in Crisis Zones

Browse the Architizer Jobs Board and apply for architecture and design positions at some of the world’s best firms. Click here to sign up for our Jobs Newsletter.

“You never know where and when the missiles will come,” says Maria Povstyana, clarifying, as if it were needed, how challenging logistics can be in the world’s most visible war zone.

Povstyana has spent 15 years in architecture and design. The last four of those years have been with Kyiv-based Balbek Bureau, where she has led the studio’s largest projects, including China’s Darron Incubation Center and the K3 office in Kyiv. However, a new collaboration with HIT* (Humanitarian Innovative Technologies) is arguably the most meaningful and impactful work of her career to date — and in the firm’s storied history.

Now in month 14, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has resulted in devastation on an unimaginable scale. As of January 2023, the National Council for the Recovery of Ukraine from the Consequences of the War at the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) estimates the cost of rebuilding will be $137.8 billion. A huge task, it has already inspired WZMH’s Speedstac prefab system, whereby parts of damaged apartment buildings could be replaced without the need to demolish entire towers.

External rendering of the new Lviv Primary School, Ukraine, by Balbek Bureau.

Infrastructure in particular has been heavily targeted by attacks. In October last year, reports suggested 30% of power stations had been taken offline, or completely leveled. And the trail of destruction has decimated many other vital services; not least schools, with a crisis now emerging within the crisis as some children have spent months without classes simply because they have no classroom left.

Povstyana is leading efforts to help this area recover. Responding to the calls of Andriy Sadovyi, Mayor of Lviv, her team has designed a testbed primary school which will be constructed via 3D printing, meaning the facility could be built and operational in around two months. The hope is the model might then be applied to other areas domestically and inform rapid deployment of essential buildings in more crisis zones.

“The main idea of the project is that there are lots of houses destroyed, and a lot of schools also. So we need to find a solution to rebuild these cities fast, using innovative technologies, and make them look good. There is lots to consider; speed, making sure what we create is useful and is a good design,” says Povstyana, speaking to Architizer via cameraphone from a nondescript stairwell in Boston, where she’s currently based. Traveling overseas when war broke out, she has been unable to return home and now works remotely.

A classroom inside the Lviv Primary School, Ukraine, by Balbek Bureau.

Communal areas in the new Lviv Primary School, Ukraine, by Balbek Bureau.

“Our concept for the building took two months. Then it was a little bit delayed with the printer and weather… and you cannot predict anything in the war…. Sometimes this part of the country gets quiet, sometimes there are a lot of attacks, missiles, everything,” she continues. “I would need to check exactly, but I think the walls should be built in about one month.”

While most 3D-printed buildings use prefabricated parts made elsewhere then transported to a site, the Lviv project is taking the opposite approach. The printer itself has been brought to Ukraine, and it will create the school sections in situ, where the building will eventually stand.

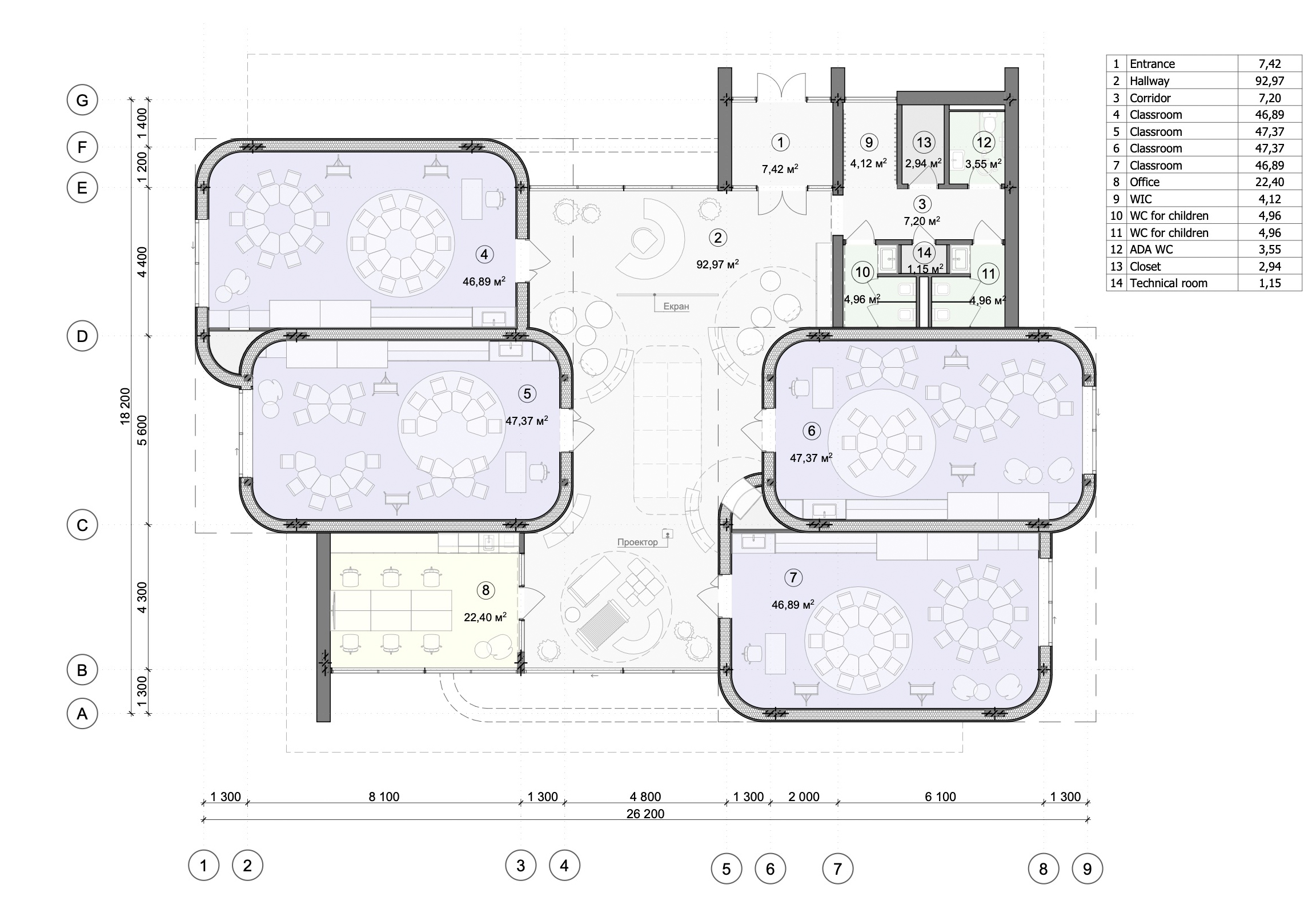

We assume this is simply safer than moving many separate pieces through volatile territories where fighting might break out at a moment’s notice, but Povstyana quickly corrects us. The floorpan has actually been informed by the limitations of technology, design largely made up of four equally-sized classrooms, joined by communal areas for sports, play and social interactions.

Final floorplan of the Lviv Primary School by Balbek Bureau.

“The printer has its maximum sizes, and it cannot go bigger — these are the largest it can do. To move the printer costs a lot of money, but we have done this as it’s [more efficient] to make each box area the maximum square footage, meaning those sections are too big to transport,” she tells us, explaining internal layouts focused on multimodal use of spaces. Areas can easily be adapted and altered to suit changing needs.

Aesthetics match for simplicity, with walls clad in stucco then painted, and vinyl covered flooring. For all intents and purposes, inside the school will resemble any other built in far less exceptional circumstances, but the opposite is true outside. Here, bold textures will be left exposed in a bid to demystify how 3D printing works, in turn showing people what it can achieve.

“3D printing has huge potential for projects like this, it could be used for the housing, too. But it depends on the climate… it has strengths and weaknesses… but where the climate is between hot and cold there’s a good opportunity for it to work well. Then it also depends on cost,” says Povstyana, before explaining that despite the high price of the equipment, significant savings can be made on labour. “As architects, our mission is to make something that is not expensive, and gives a new look to our country with fast solutions… Every community, every part of the country, will show us what’s needed the most, because every part has its own situation.”

Browse the Architizer Jobs Board and apply for architecture and design positions at some of the world’s best firms. Click here to sign up for our Jobs Newsletter.