From the RECORD Archives: ‘The Post-Modern House’

✕

Writing in May 1945, just months before the end of World War II, architect Joseph Hudnut urged his contemporaries to transcend the “engineered home”—to craft with heart what is, after all, the oldest and most intimate of spaces. Dissatisfied with the prefabricated homes that were then proliferating throughout New England, Hudnut, the founding dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, took to the pages of RECORD to argue against technologically driven design that shunted architectural form-making. Although Hudnut does little to define the “Post-Modern” mentioned in the title, his evocative essay is often cited as the first use, in an architectural context, of a vexed term that would later dominate discourse in the 1970s and ’80s. Interestingly, Hudnut was one of the earliest American architects to recognize the importance of the modern movement—and famously invited Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer to join the Harvard faculty.

Editor’s note: This article has been condensed for ease of online reading but reflects the original text.

© Architectural Record, May 1945

“The Post-Modern House”By Joseph HudnutArchitectural Record, May 1945

JOSEPH HUDNUT, Dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, is the logical critic to present this provocative philosophy because his own progressiveness, as well as his penetrating mind and persuasive pen, compel attention to the reminder that “houses will still be built out of human hearts.” He challenges architects to push forward beyond the “engineered house—“God forgive us”—to something that will not only facilitate the daily functions of humans, but also illumine their lives.

I have been thinking about that cloudburst of new houses which as soon as the war is ended is going to cover the hills and valleys of New England with so many square miles of prefabricated happiness. I have been trying to capture one of these houses in my mind’s eye, to construct there its form and features, to give it, if you will pardon me, a local habitation and a name.

In this effort I have not been widely aided by the architectural press. I am shown there the thousand ways in which architects exploit the new inventions of industry. I am made aware of new techniques of planning and the surprising gadgets with which our houses are to be threaded. I perceive also the aesthetic modes which these innovations have occasioned: the perforated box, the glorified woodshed, the house built on a shelf, the house with its bones “dynamically exposed.” These excite my imagination; and yet they fail somehow to furnish it with that totality of impression toward which these experiments in structure and physiognomy are or ought to be addressed. It seems to me that these houses with some exceptions have left unexhibited that idea which is the essential substance of a house. I do not discover in them that emotional content which might cement their curious shapes, that promise which in architecture is the important aspect of all appearances.

My impression is obviously shared by a very wide public and I think that this circumstance explains in part the persistence with which people, however enamored of science, cling to the familiar patterns of their houses. Among the soldiers who write letters to me there is, for example, one in New Guinea who asks me to provide the new house which I am to build for him with every labor-saving device known to modern science and every new idea in planning, in building materials and in air conditioning, and who ends his letter with the confident hope that these will not make the slightest change in the design of the house. He has in mind, if I have understood him correctly, a Cape Cod cottage which, upon being opened, will be seen to be a refrigerator-to-live-in. I shouldn’t be surprised to learn that his requirements reflect accurately those of the Army, the Navy, the Marines, the WAC, and the WAVES.

Our soldiers and sailors are already sufficiently spoiled with flattery and yet I must admit that here is still another instance in which their prescience overleaps our judgment. Beneath the surface naiveté of my soldier’s letter there is expressed an idea which is of critical import to architecture: a very ancient idea, to be sure, but one which seems to be sometimes forgotten by architects. The total form and ordinance of our houses are not implied in the evolution of building methods or utilities. They do not proceed merely from these; they cannot be wholly from these premises. In the hearts of the people at least they are relevant to something beyond science and the uses of science.

Now I think that this relevance—which our soldier quaintly discovers in the Cape Cod cottage—is obscured in our contemporary practice by two interests: interests which are sometimes related and sometimes distinct. One of these has its source in a professional delight in the swift march of our triumphant technologies; the other in an excessive concern for aesthetic effects for their own sake—and especially in these effects when they are specific to our new methods of construction. There is a very large number of architects nowadays who assume the attitudes and ideals of scientists, finding a sufficient reward for their work in the intellectual satisfactions afforded by technologies. Some of these appear to be quite indifferent to the formal consequences of their constructions, beauty being a flower which will spring unbidden from beneath their earnest feet; while others discover with such an excess of fervor the aesthetic and dramatic possibilities of their new structures that they forget to ask if these are appropriate to the idea to be expressed. There are also architects, highly praised by museum critics, who take little note of science, or indeed of professional competence in general, except as a source of new abstractions in materials and in space, the exciting elements of a precious and very exclusive Heaven.

I am constantly surprised by the vehemence with which architects assert the scientific nature of their activities. They will allow no felicity of form to go unexplained by economic necessity or technical virtuosity. Beauty cannot be enjoyed until justified as a consequence of the slide-rule, and frequently her presence in their calculated halls will be acknowledged only after a heated argument.

The other day, when talking to an architect, I made a most unfortunate slip of the tongue: I called him an artist. He challenged me at once to a duel saying that the word is one which in our profession no gentleman would use toward another. Designer might be said thoughtlessly or in jest, but artist admitted of no possible reconciliation.

I am for every change in construction or equipment or organization which will promote comfort or security or economy in the modern house. Nevertheless, there is, I think, an attitude of mind, a valuation or—perhaps more precisely—a way of working which is more important in architecture than our science and which is by no means universal in our practice. I mean that way of working which gives to things made by men and to things done by men qualities beyond those demanded by economic or social or moral expediency, the way of working which complements utility with the spiritual qualities of form, sequence, rhythm, felt relationships. I mean that kind of making and doing which illumines life, gives it meaning and dignity and which, through education, make life a common experience. I mean, in short, that search for expression which transforms the science of building into the art of architecture.

If a dinner is to be served, it is art which dresses the meat, determines the order of serving, prepares and arranges the table, establishes and directs the conventions of costume and conversation, and seasons the whole with that ceremony which, long before Lady Macbeth explained it to us, was the best of all possible sauces. If a story is to be told, it is art which gives the events proportion and climax, fortifies them with contrast, tension and the salient word, colors them with metaphor and allusion, and so makes them cognate and kindling to the heart. If a prayer is made, it is art which sets it to music, surrounds it with ancient observances, guards it under the solemn canopies of great cathedrals.

© Architectural Record, May 1945

The shapes of all things made by man are determined by the functions, by the laws of materials and the laws of energies, by marketability (sometimes) and the terms of manufacture; but these shapes may also be determined by the need, more ancient and more imperious than your crescent techniques, for some assurance of importance and worth in those things which encompass humanity. That is true of all forms of doing, of all patterns of work and conduct and pageantry. It is true of the house and of all that takes place in the house; for here among all things made by man is that which presses most immediately upon the spirit—the symbol, the armor, and the hearth of a family. The temple itself grew from this root; and the House of God, which architecture celebrates with her most glorious gifts, is only the simulacrum and crowning affirmation of that spiritual knowledge which illumined first the life of the family and only afterwards the lives of men living in communities.

Here is the shelter which man shaped in the earth one hundred thousand years ago, the pit which became the wattle hut, the cave, the mound dwelling, the mandan lodge and the thousand other constructions with which our restless invention has since covered the earth: the shelter which in a million forms has accompanied his long upward journey, his companion and shield and outer garment. Here is that home which first shaped and disciplined his emotions and over centuries formed and confirmed the habits and valuations upon which human society rests. Here is that space which man learned to refashion into patterns conformable to his spirit: the space which he made into architecture.

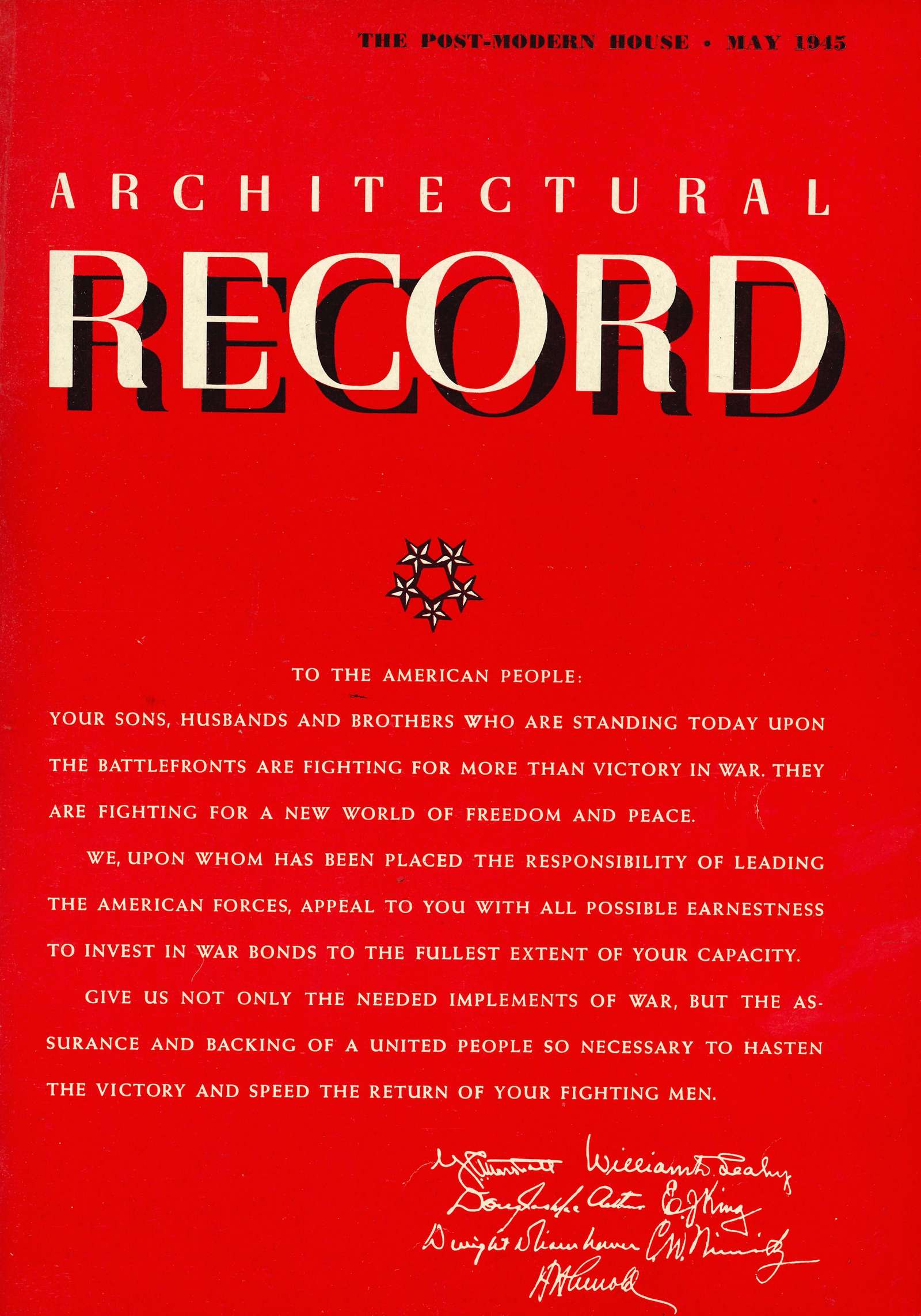

This theme, so lyrical in its essential nature, can be parodied by science. An excess of physiological realism, for example, can dissemble and disfigure the spirit quite as ingeniously as that excess of sugar which eclecticism in its popular aspect pours over the suburban house. A “fearless affirmation” of the functions of nutrition, dormation, education, procreation and garbage disposal is quite as false a premise for design as that clutter of rambling roofs, huge chimneys, quaint dormers, that prim symmetry of shuttered window and overdoor fanlight, which forms the more decorous disguise of Bronxville and Wellesley Hills; nor have I a firmer faith in the quaint language and high intentions of those sociologists who arrive at architecture through “an analytical study of environmental factors favorable to the living requirements of families considered as instruments of social continuity.” I am even less persuaded by biologists: especially those who have created a vegetable humanity to be preserved or cooled or propagated in boxes created for those purposes. I mean those persons who make diagrams an action-photographs showing the impact upon space made by a lady arranging a bouquet or a gentleman dressing for dinner or 3.81 children playing at kiss-in-the-ring—and who then invite architects to fit their rooms around these “basic determinants.” My requirements are somewhat more subtle than those of a ripe tomato or a caged hippopotamus, whatever may be the opinion of the Pierce Foundation.

Now I do not advocate a return to the Cape Cod cottage, however implacably technological its interior—still less a return to that harlequinade of Colonial, Regency, French Provincial, Tudor, and Small Italian Villa, the relics and types of our ancestor’s inexhaustible inventiveness, which adds such dreary variety to our suburban landscapes. I think we may assume, a soldier’s taste notwithstanding, that that adventure is at an end. Yet I sometimes think that the eclectic soul of these suburbs is, by intuition if not by understanding, nearer the heart of architecture than those rigid minds which understand nothing but the “economics of shelter and the arid technicalities of construction.” Among the architects of the late XIX Century there were no doubt many who were merely experimenters in the science of taste and many who were merely merchant-architects, their shelves well-stocked with marketable prejudices; but are not these the plague of every era? There were also architects in those days who, however they may have leaned upon history, yet conceived their houses as invitations to the spirit. We are at home in these houses even though our world cannot enter with us. Inapposite as they are to our times, they yet represent an art of escape which was at least widely authentic: an art of escape, but nevertheless an art.

I am inclined to explain the persistence of the styles of architecture on some other ground than that of association, although of course that is an important factor. We are not all fools of habit. I think that we overlook the way in which these inherited patterns sometimes recapture the idea once expressed—more eloquently to be sure—by their prototypes. After they have ceased to have any harmony with modern techniques of construction or with modern habits of living they yet speak to us of peace and security, of romantic love and the tender affection of children, of an adventure re-lived a thousand million times; we understand them as we understand a song sung in a language unknown to us. They remain, however alien to the business of life, the elements of an art.

We have developed in our day a new language of structural form. That language is capable of deep eloquence; and yet we use it only infrequently for the purposes of a language. Just as the styles of architecture are detached from modern technologies and by that detachment lose that vitality and vividness which might come from a direct reference to our own times, so our new motives are detached from the idea to be expressed. They have their origin not in the idea but in techniques. We have not yet learned to give them any persuasive meanings. They have interesting aesthetic qualities, they arrest us by their novelty and their theater, but they have nothing to say to us.

© Architectural Record, May 1945

The architects of the Georgia tradition were as solicitous of progress and designed their houses with the same care for serviceability that they spent on the design of a coach, and yet their first consideration was for their way of life. When I visit the streets of Salem I am not so confident as are some of my colleagues that they suffered from a limited range of materials and structural methods. We are too ready to mistake novelty for progress and progress for art. I tell my students that there were noble buildings before the invention of plywood. They listen indulgently but they do not believe me.

We have to defend our house not only against the new techniques of construction but also against the aesthetic forms which these engender. We must remember that techniques have no inherent values as elements of expression; their competence lies in the way we use them. However they may interest us, they have no place in the design of a house unless they do indeed serve the purposes of the home and are congenial to its temper. When, as often happens, their only virtue is their show, their adventitious nature is soon realized; they are as great a burden to our melody as an excess of ornamentation. That mighty cantilever which projects my house over a kitchen yard or waterfall, the lacustrian vertiginous Lally column, the “stressed skin” and the flexible wall, the fanaticisms of glass brick, the strange hoverings of my house above the firm earth: these strike my eyes but not my heart. A master can—at his peril—use them but for human nature’s daily use we have still proportion, homely ordinance, quiet wall surfaces, good manners, common sense and love. These are also excellent building materials.

The world will not ask architects to tell it that this is an age of invention of new excitements and experiences and powers. The airplane, the radio, the V-bomb and the giant works of engineering will give that assurance somewhat more persuasively than the most enormous of our contraptions. Beside the big top industry our bearded lady will not long astonish the mob.

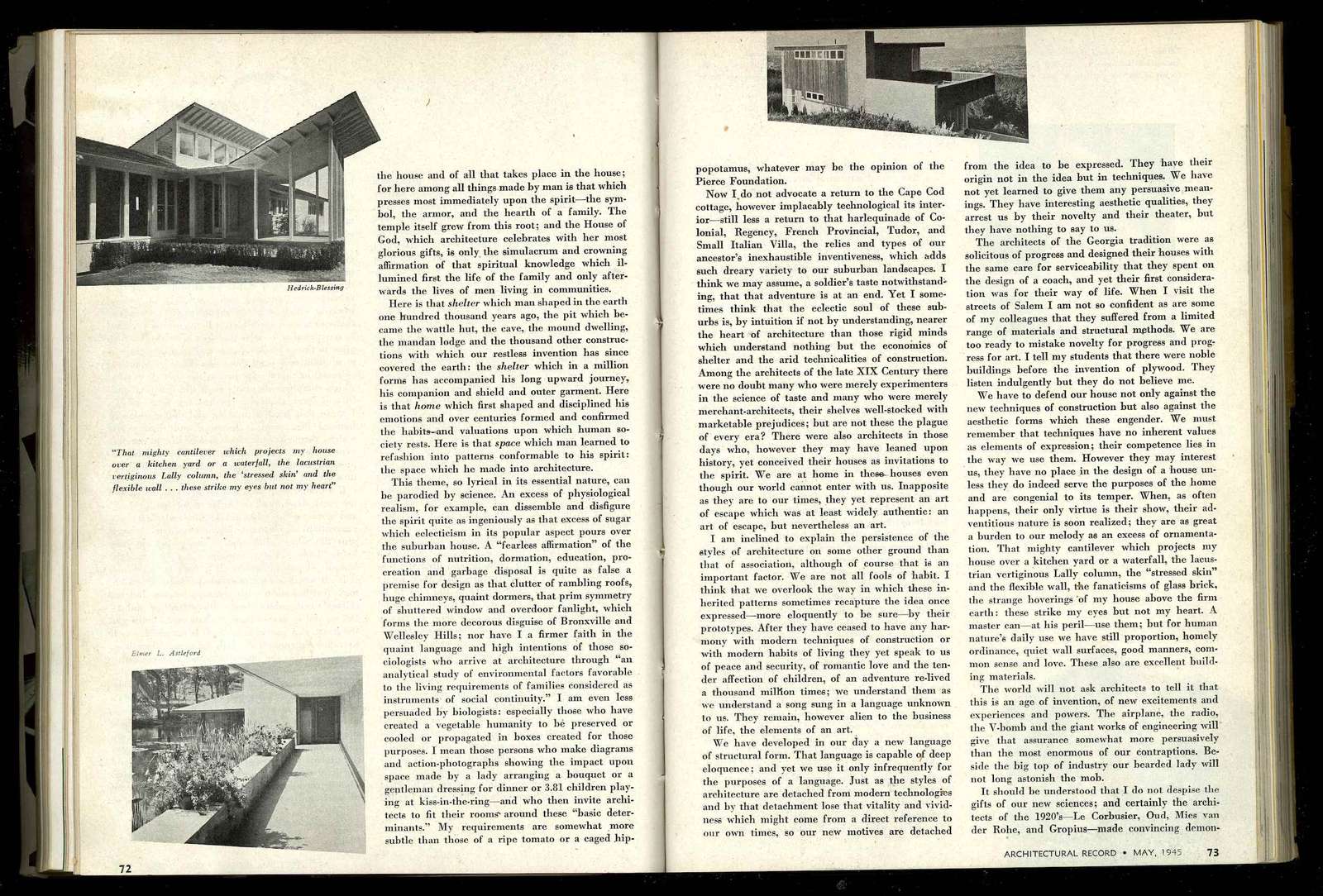

It should be understood that I do not despise the gifts our new sciences; and certainly the architects of the 1920’s—Le Corbusier, Oud, Mies van der Rohe, and Gropius—made convincing demonstrations of the utility of these in an art of expression. They used structural inventions not for their own sake or yet for the sake of economy and convenience merely but as elements in a language. Functionalism was a secondary characteristic of their aristocratic art which had as its basic conception, so far as this is related to the home, a search for a form which should exhibit a contemporary phase of that ancient aspect of life. To this end new materials were used, old ones discarded; but the true reliance was not upon these but upon new and significant relationships among architectural elements—among which enclosed space was the prime medium, walls and roofs being used as a means of establishing spatial compositions. To compose in prisms rather than in mass, to abolish the facade and deal in total form, to avoid the sense of enclosure, to admit to a precise and scrupulous structure no technique not consonant with the true culture of our day: these were the important methods of an architecture never meant to be definitive or “international”—which offered rather a base from which a new progress might be possible, a principle which should have its peculiar countenance in every nation and in every clime. I should not venture here to restate a creed already so often stated had not a torrent of recent criticism distorted this architecture into a “cold and uncompromising functionalism,” had it not been made the excuse for an arid materialism wholly alien to its intention.

We must rely not upon the wonder and drama of our inventions but upon the qualities, beyond wonder and beyond utility, which we can give them. Take, for example, space. Of all the inventions of modern architecture the new space is, it seems to me, the most likely to attain a deep eloquence. I mean by this not only that we have attained a new command of space but also a new quality of space. Our new structure and our new freedom in planning—a freedom made possible in part at least by the flat roof—has set us free to model space, to define it, to direct its flow and relationships; and at the same time these have given space an ethereal elegance unknown to the historic architectures. Our new structure permits almost every shape and relationship in this space. You may give it what proportion you please. With every change in height and width, in relation to the spaces which open from it, in the direction of the planes which enclose it, you give it a new expression. Modern space can be bent or curved; it can move or be static, rise or press downward, flow through glass walls to join the space of patio or garden, break into fragments around alcoves and galleries, filter through curtains or end abruptly against a stone wall. You may also give it balance and symmetrical rhythms.

If then we wish to express in this new architecture the idea of home, if we wish to say in this persuasive language that this idea accompanies, persistent and eloquent, the forward march of industry and the changing nature of society, we have in the different aspects of space alone a wide vocabulary for that purpose.

I have of course introduced this little dissertation on space in order to illustrate this resourcefulness. I did not intend a treatise. I might with equal relevance have mentioned light which is certainly as felicitous a medium of modern design, or the new materials which offer so diversified a palette of texture and color, or the forms and energies of our new types of construction, or of the relationships to site and to nature made possible by new principles of planning. There are also the arts of painting and sculpture, of furniture-making, of textiles, metal ware and ceramics—all of which are, or ought to be, harmonious accessories to architecture.

When I think of all these elements, so varied, so impressible, so unhackneyed, which lie at our hand ready to be fused into the patterns of our houses, I am astonished that architects should have need of a science to sustain their role in the life of our times. Science, I sometimes think, is a defense mechanism, at least in part. We were at too great pains a generation ago to advertise the romantic overtones of our art; we must now live down our reputation, only too well-deserved, as decorator and dealer in sentiment; and we display this haircloth to reassure those practical-minded who might otherwise prefer the engineer. Our forfeit is that we must look (and think) like an engineer. We must have—God forgive us—an engineered house.

I have heard architects explain with formulae, calculation, diagram and all manner of auricular language, the advantages of the glass wall—of wide areas of plate glass opening on a garden—when all that was necessary was to say that here is one of the loveliest ideas ever entertained by an architect. People who feel walls do not need to compute them; and people who are deaf to the rhythms of great squares of glass relieved by quiet areas of light-absorbing wall may as well resign the enjoyment of architecture. Because we are free of those “holes punched in the wall,” of that balance and stiff formalism in window openings which proclaim the Georgian mode, because we can admit light where we please and in what quantity we please, we have in effect invented a new kind of light. We can direct light, control its intensity and its colorations; diffuse it over space, throw it in bright splashes against a wall, dissolve it and gather it up in quiet pools; and from those scientists who are work on new fashions in artificial light we ought to expect not new efficiencies merely or new economies merely, but new radiances in living.

Of course I know that modern architecture must adjust its processes to the evolving pattern of industry, that building methods must attain an essential unity with all the other processes by which in this mechanized world materials are assembled and shaped for use. No doubt the wholesale nature of our constructions imposes upon us a monotony and banality beyond that achieved by past architectures—a condition not likely to be remedied by prefabrication—and no doubt our houses, as they conform more closely to our ever-advancing technologies, will escape still further the control of art. Still more inimical to architecture will be those standardizations of thought and idea already widely established in our country; that assembly-line society which stamps men by the millions with mass attitudes and mass ecstasies. Our standards of judgment will be progressively formed by advertisement and the operations convenient to industry.

I shall not imagine for my future house a romantic owner, nor shall I justify this client’s preferences as those foibles and aberrations usually referred to as “human nature.” No, he shall be a modern owner, a post-modern owner, if such a thing is conceivable. Free from all sentimentality or fantasy or caprice, his vision, his tastes, his habits of thought shall be those most serviceable to a collective-industrial scheme of life; the world shall, if it so pleases him, appear as a system of casual sequences transformed each day by the cumulative miracles of science. Even so, he will claim for himself some inner experiences, free from outward control, unprofaned by the collective conscience. That opportunity, when all the world is socialized, mechanized and standardized, will yet be discoverable in the home. Though his house is the most precise product of machine processes, there will be entrenched within this ancient loyalty invulnerable against the buffetings of the world.

It will be the architect’s task, as it is now, to comprehend that loyalty—to comprehend it more firmly than any one else—and, undefeated by all the armaments of industry, to bring it out in its true and beautiful character. Houses will still be built out of human hearts.