From the RECORD Archives: ‘A Chapel for Tuskegee by Rudolph’

✕

© Architectural Record, November 1969, photo by Ezra Stoller, click to enlarge

On the occasion of The Tuskegee Chapel: Paul Rudolph X Fry & Welch, an exhibition about the masterwork on display at the Yale Architecture Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, the editors are republishing online a cover story that first appeared in the November 1969 issue, written by former RECORD editor in chief Mildred Schmertz. Then senior editor, Schmertz hailed the chapel as “one of the most dramatic and powerful religious spaces to be built in this century” and “worth a pilgrimage.” Rudolph suggested as much to Ezra Stoller whose images illustrate the article, when he wrote to the photographer earlier that year asking him to document it. “The Record want[s] to do it . . . It is my best building, others say,” Rudolph wrote. This letter also appears in the exhibition, which closes July 5, 2025.

Editor’s note: This article has been condensed for ease of online reading but reflects the original text from 1969.

A Chapel for Tuskegee by Rudolph

By Mildred F. Schmertz

Architectural Record, November 1969

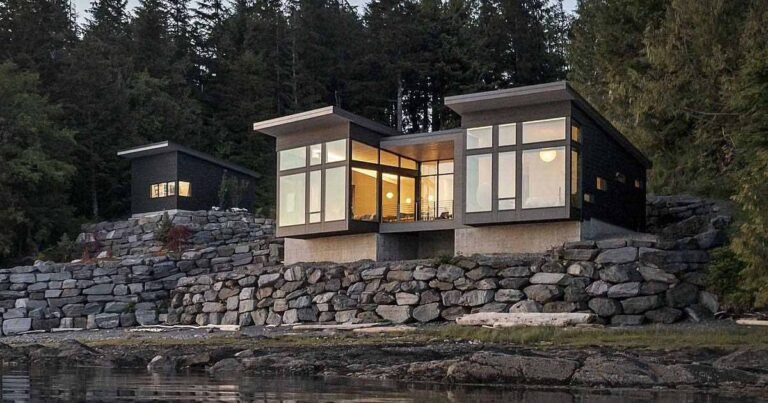

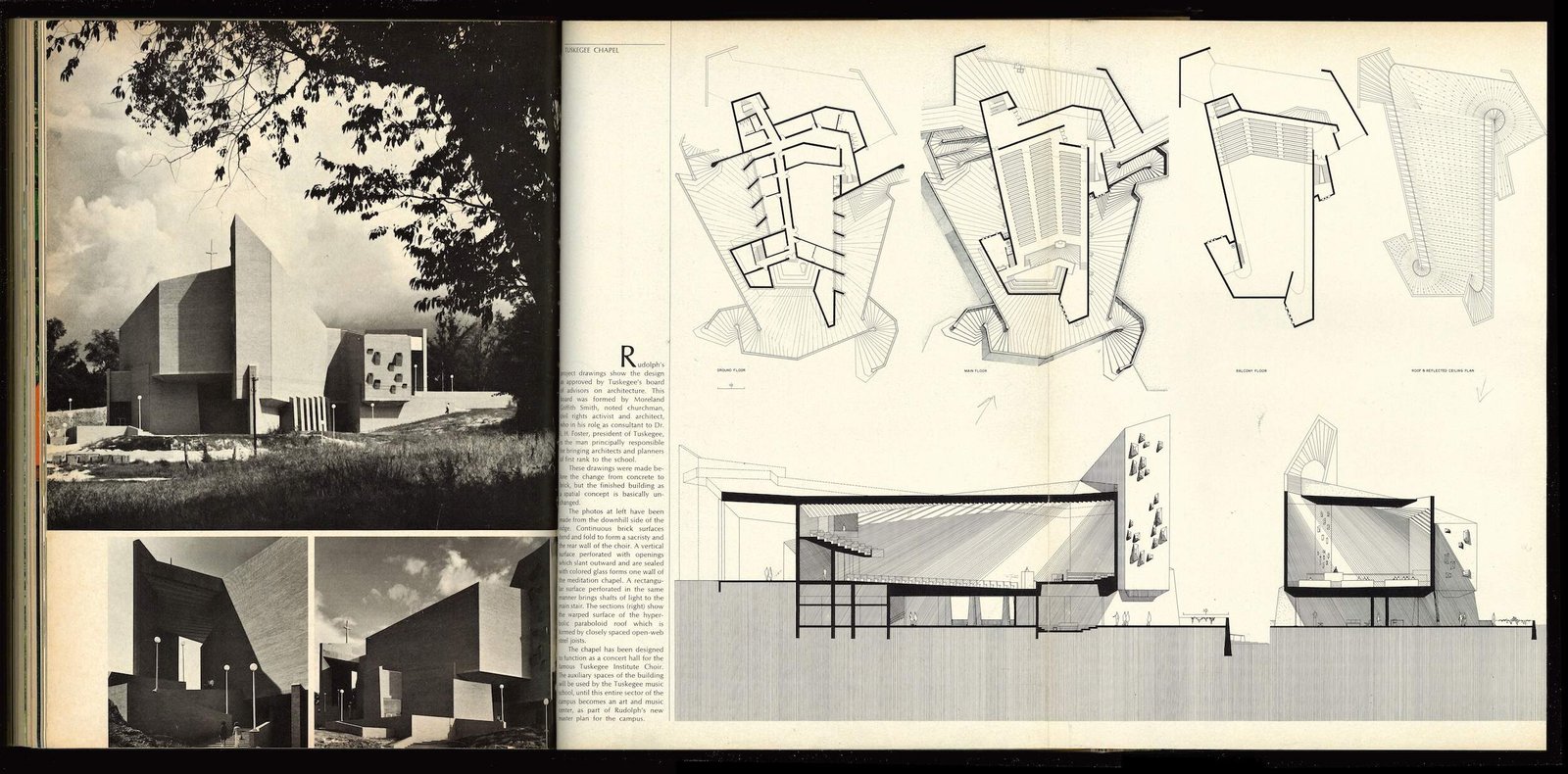

The recently completed chapel for Tuskegee Institute [now Tuskegee University], a 2,000-student Negro college in Tuskegee, Alabama, may be Paul Rudolph’s best work to date. Designed in collaboration with the firm of Fry and Welch (both black architects), it is an outstanding, original, and remarkably effective religious building. It possesses the symbolic power of Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp—acknowledged by Rudolph as a source—and is clearly influenced by Wright, especially inside. The ideas of Corbu and Wright, however, have been transformed by the architect’s creative imagination to achieve a unique and highly personal work of art.

© Architectural Record, November 1969, photo by Ezra Stoller

Because the Christian faith has been and will continue to be the major ideological force behind the founding and growth of this interdenominational school, and a major historical force behind the black man’s struggle for equality in the United States, a strong sense of rightness made the administrators of Tuskegee wish to replace their old chapel, struck by lightning and burned to the ground in 1957, with the finest church they could afford by the best architect they could find. Unfortunately, because their fine new chapel has been built for and by Negroes in the deep South, many observers will be tempted to see qualities in the church which evoke the Negro struggles in a literary way—to see the building, for example, as a walled, windowless fortress open only to the sky and sheltering its occupants from a hostile environment.

Such fantasies, while understandably comforting to some, miss the point. The highly abstract forms of the Tuskegee chapel are universal symbols, relevant to all Christians. Rudolph’s chapel, given a similar site and program, would be as right for Harvard as for Tuskegee, and this is as it should be.

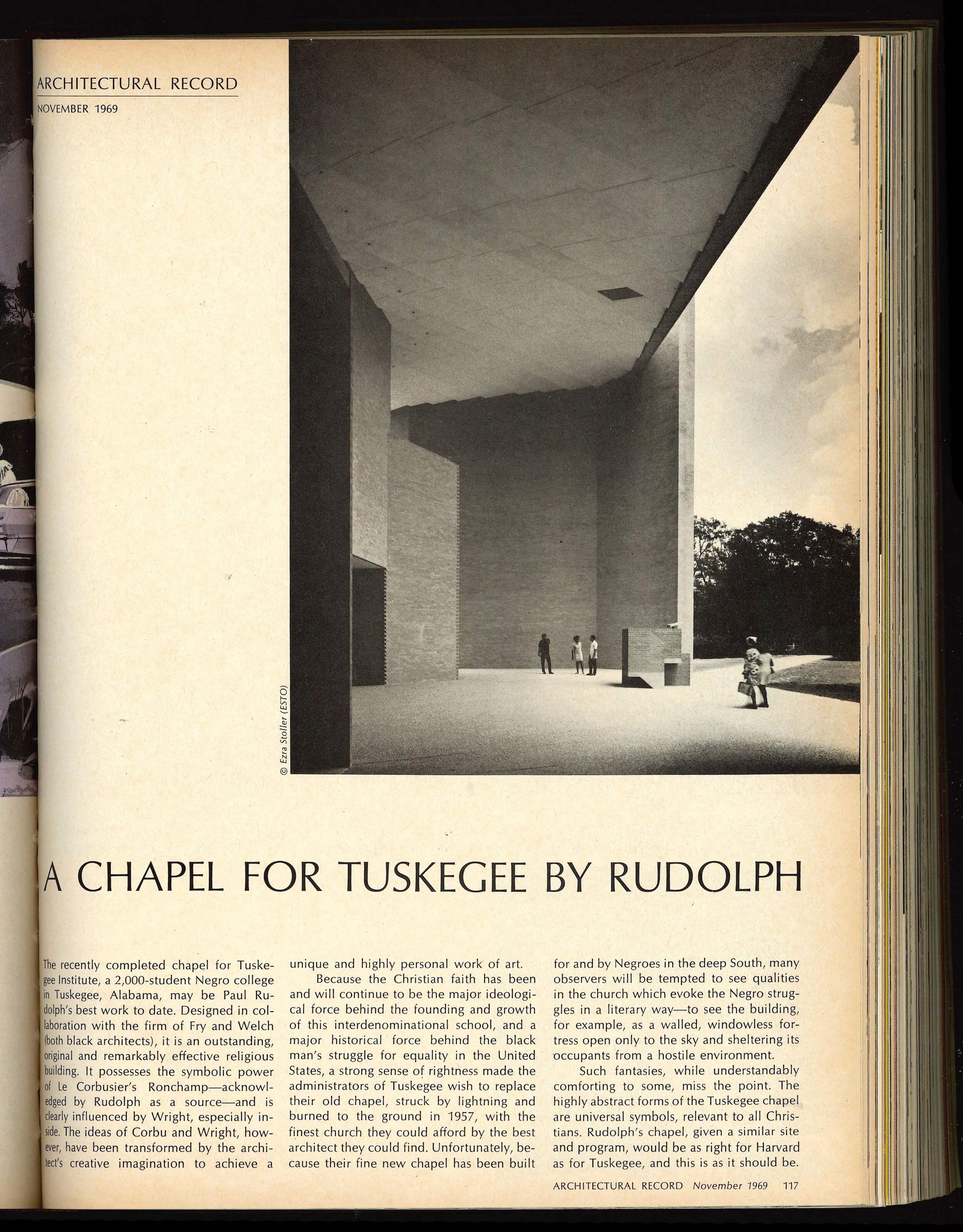

The chapel is the focal point of the campus and has been constructed near the site of the burned-down church it replaces. The photographs show the principal entrance located at the top of a broad ridge which runs through the center of the older part of the campus near the graves of Booker T. Washington and George W. Carver (the former the first principal and guiding force of the school, and the latter its first great scientist). This part of the school grounds still bears handsome traces of the original landscape plan by Frederick Law Olmsted, the first “advocacy planner” whose concern for the cause of Southern Blacks began in his youth before the Civil War and continued throughout his career.

© Architectural Record, November 1969, photo by Ezra Stoller

The roof of the chapel slopes boldly upward on its long axis, as at Ronchamp, and beneath its broad overhand the outdoor pulpit juts assertively forward in vertical space, just as it does on that famous French hilltop. The church was originally designed to have poured-in-place concrete walls supporting a hyperbolic paraboloid roof of open-web steel frames supporting brick cavity walls. The light-pink mechanically produced brick lacks the character of the handmade bricks in the early Tuskegee buildings, which were molded by student bricklayers and fired in their own kilns, but it is as appropriate to the highlight sophisticated building it sheathes as the handmade bricks are to the humbler structures which surround it.

Rudolph’s project drawings show the design as approved by Tuskegee’s board of advisors on architecture. This board was formed by Moreland Griffith Smith, noted churchman, civil rights activist, and architect, who in his role as consultant to Dr. L.H. Foster, president of Tuskegee, is the man principally responsible for bringing architects and planners of first rank to the school.

© Architectural Record, November 1969, photo by Ezra Stoller

Continuous brick surfaces bend and fold to form a sacristy and the rear wall of the choir. A vertical surface perforated with openings which slant outward are sealed with colored glass forms one wall of the meditation chapel. A rectangular surface perforated in the same manner brings shafts of light to the main stair. The sections show the warped surface of the hyperbolic paraboloid roof which is formed by closely spaced open-web steel joists.

The chapel has been designed to function as a concert hall for the famous Tuskegee Institute Choir. The auxiliary spaces of the building will be used by the Tuskegee music school, until this entire sector of the campus becomes an art and music center, as part of Rudolph’s new master plan for the campus.

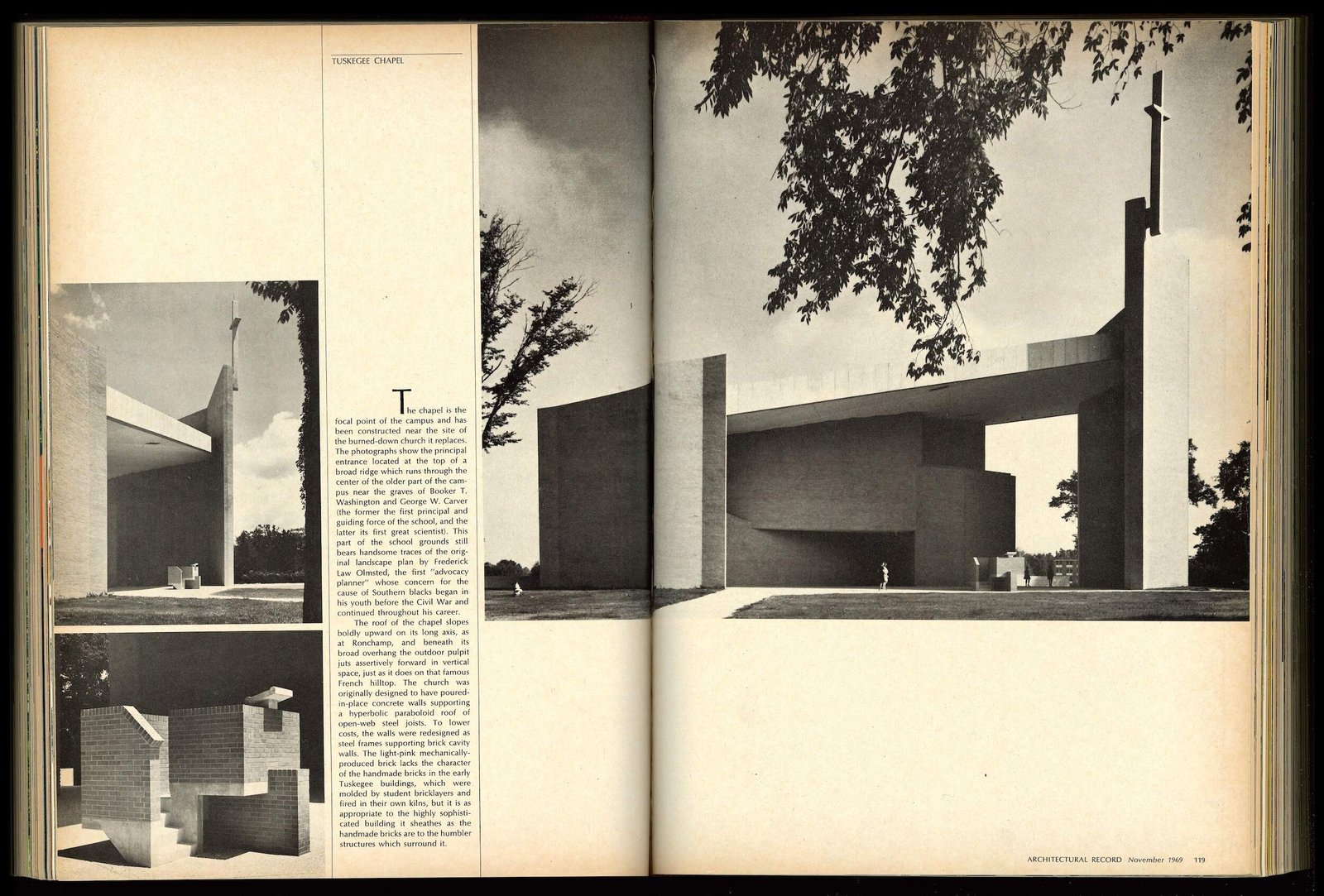

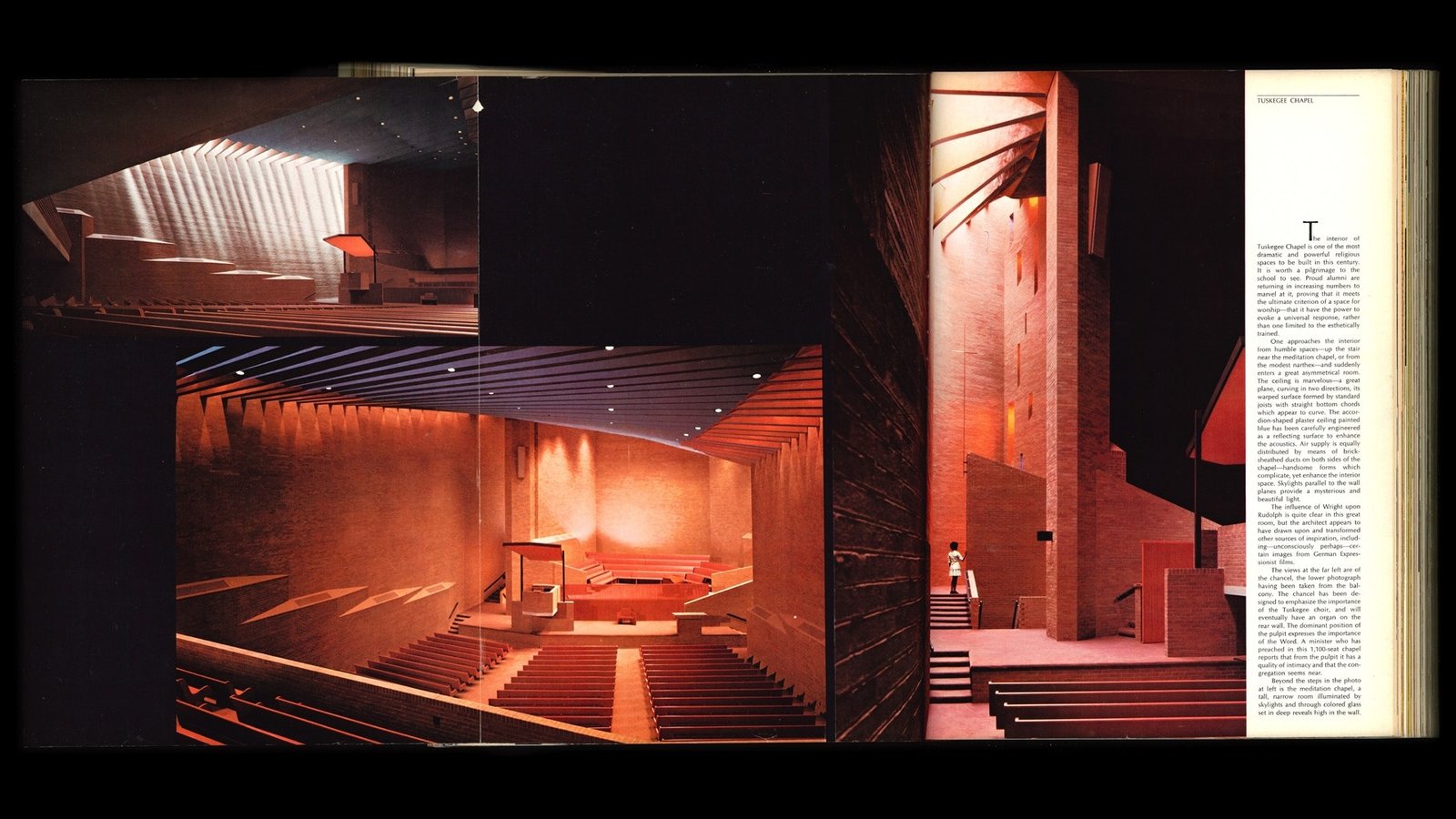

The interior of the Tuskegee Chapel is one of the most dramatic and powerful religious spaces to be built in this century. It is worth a pilgrimage to the school to see. Proud alumni are returning in increasing numbers to marvel at it, proving that it meets the ultimate criterion of a space for worship—that it have the power to evoke a universal response, rather than one limited to the aesthetically trained.

© Architectural Record, November 1969, photo by Ezra Stoller

One approaches the interior from humble spaces—up the stair near the meditation chapel, or from the modest narthex—and suddenly enters a great asymmetrical room. The ceiling is marvelous—a great plane, curving in two directions, its warped surface formed by standard joists with straight bottom chords which appear to curve. The accordion-shaped plaster ceiling painted blue has been carefully engineered as a reflecting surface to enhance the acoustics. Air supply is equally distributed by means of brick-sheathed ducts on both sides of the chapel—handsome forms which complicate, yet enhance the interior space. Skylights parallel to the wall planes provide a mysterious and beautiful light.

The influence of Wright upon Rudolph is quite clear in this great room, but the architect appears to have drawn upon and transformed other sources of inspiration, including—unconsciously, perhaps—certain images from German Expressionist films.

The chancel has been designed to emphasize the importance of the Tuskegee choir, and will eventually have an organ on the rear wall. The dominant position of the pulpit expresses the importance of the Word. A minister who has preached in this 1,100-seat chapel reports that from the pulpit it has a quality of intimacy and that the congregation seems near.

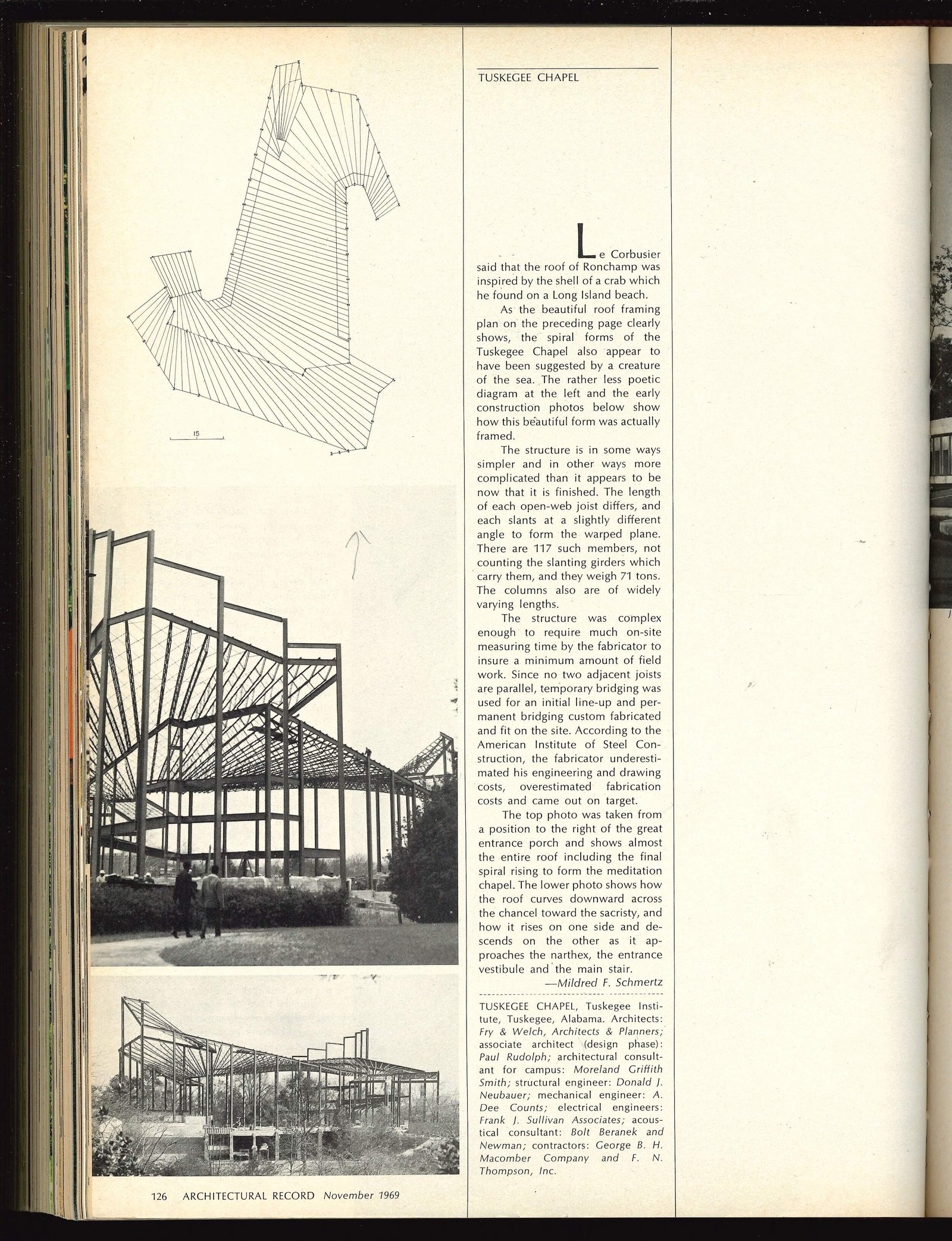

Le Corbusier said that the roof of Ronchamp was inspired by the shell of a crab which he found on Long Island beach. As the beautiful roof framing plan on the preceding page clearly shows, the spiral forms of the Tuskegee Chapel also appear to have been suggested by a creature of the sea. Early construction photos show how this beautiful form was actually framed.

© Architectural Record, November 1969, photo by Ezra Stoller

The structure is in some ways simpler and in other ways more complicated than it appears to be now that it is finished. The length of each open-web joist differs, and each slants at a slightly different angle to form the warped plane. There are 117 such members, not counting the slanting girders which carry them, and they weigh 71 tons. The columns also are of widely varying lengths.

The structure was complex enough to require much on-site measuring time by the fabricator to insure a minimum amount of field work. Since no two adjacent joists are parallel, temporary bridging was used for an initial line-up and permanent bridging custom fabricated and fit on the site. According to the American Institute of Steel Construction, the fabricator underestimated his engineering and drawing costs, overestimated fabrication costs and came out on target.

Editor’s note: This article has been edited and condensed for ease of online reading.