From the RECORD Archives: ‘A Building Designed for Scenic Effect’

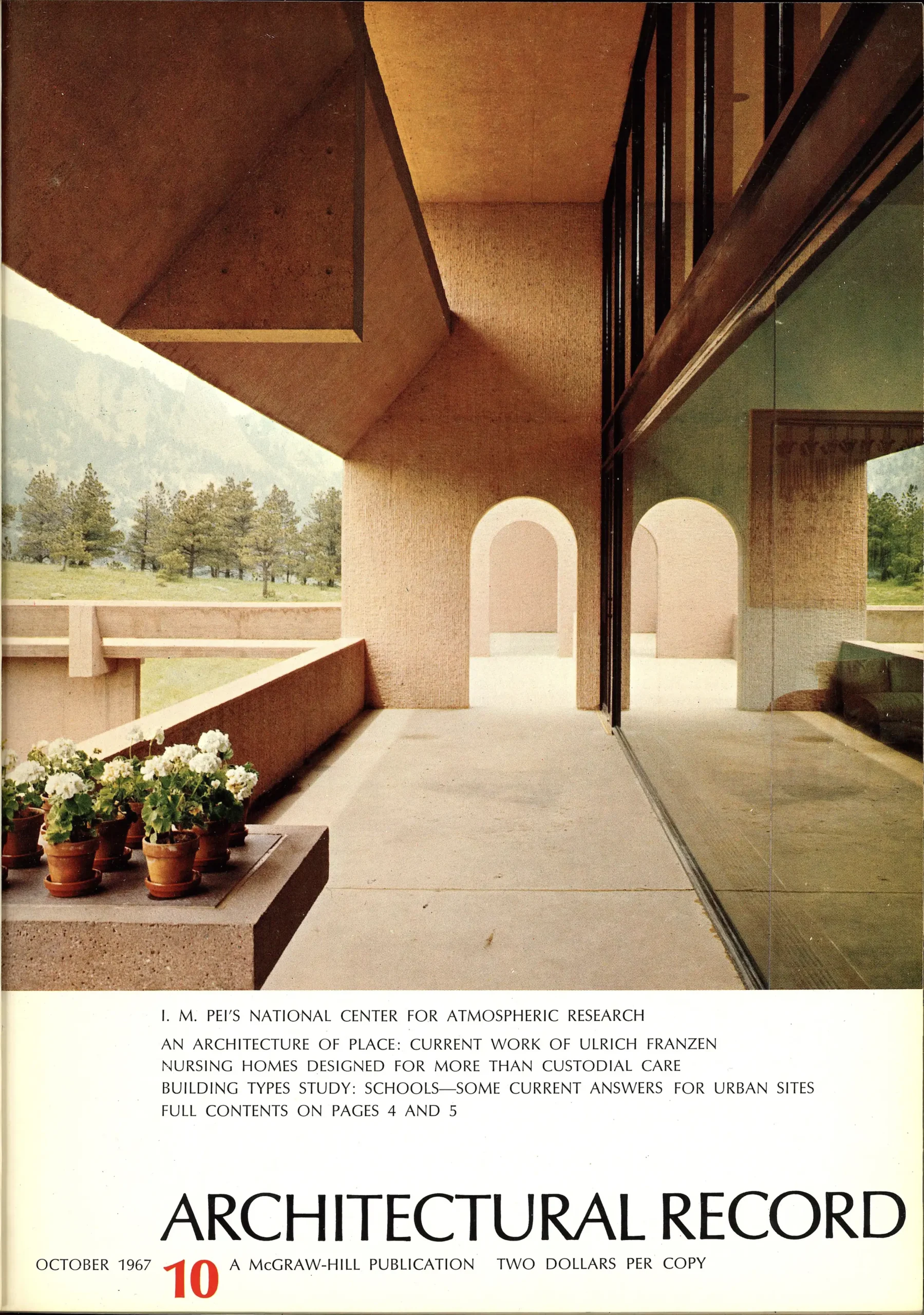

Research laboratories rarely shout an appealing aesthetic. They are often built to captivate the mind, not the eye. But when such a facility manages to do both—as in the case of I.M. Pei’s National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)—there is potential for instant spectacle. This rust-colored concrete mass, tucked into the foothills of Boulder, Colorado, reads as a bastion for science sculpted from the rockface. Inspired by the Anasazi cliff dwellings in nearby Mesa Verde, Pei stripped away the visual regularity associated with stacked floors so that his geometric forms could marry the rugged, snow-dusted Flatirons beyond. Architecture, he believed, must defer to nature: “You just cannot compete with the scale of the Rockies.” A meandering facade thus took shape, equally fitting for a program that probes our atmosphere as well as a dystopian institute in Woody Allen’s farce Sleeper (1973). NCAR first appeared in the 1967 October issue, where then associate editor Jonathan Barnett examines the intent and effect of Pei’s design, but it reappeared in 2016 as one of RECORD’s top 125 buildings.

Editor’s note: This article has been condensed for ease of online reading but reflects the original text.

© Architectural Record, October 1967

“A Building Designed for Scenic Effect”By Jonathan BarnettArchitectural Record, October 1967

I. M. Pei’s National Center for Atmospheric Research is a direct response to a spectacular site and a highly philosophical program.

I. M. Pei’s National Center for Atmospheric Research would be a difficult design to understand if it were removed from its setting on a mountainside in Boulder, Colorado. The arrangement of the building on its site is clearly the key concept, and the internal relationships—while they work well enough—do not give the building its form.

Only a few years ago architects and critics were saying that buildings would no longer be designed this way, from the outside in, as mass instead of space; and the Atmospheric Research Center does not possess the other supposedly indispensable characteristics of “Modern Architecture” either. Not only is it not a part of a uniform international style, but it is quite different from other work that Pei was designing and building at the same time; regularity and flexibility are hardly salient characteristics; the structure is not expressed; and the architect made a special effort to use indigenous materials as the aggregate for the concrete, a philosophy much more akin to those picturesque country houses built from stone quarried on the site than to modernist ideas about factory fabrication.

While we no longer expect such a building to produce a denunciation in some English architectural magazine (with the architect being excommunicated from the modern movement’s “main stream” and some general aspersions about American frivolousness and lack of serious architectural understanding) we are still having trouble lining up architectural philosophies with what architects are actually doing. There has been much speculation that architecture is entering a “Mannerist” phase of complexity and contradiction. In evaluating this idea it is important to separate the complexities and contradictions which are actually architectural from those which exist only in the mind of the theorist. Much of what is happening today can be viewed as traditional, with architects trying to respond to important problems by discovering the essence of ideas that had produced successful solutions to such problems in the past.

© Architectural Record, October 1967, photo by Ezra Stoller/ESTO

The Atmospheric Research Center is a traditional building in that sense, and a direct response not only to the character of the site, but to the basic nature of the program as well.

The site was selected by the client well before the process of interviewing architects began. The client, a non-profit corporation that receives funds from the National Science Foundation but is owned by a consortium of universities, is a national center for interdisciplinary research into all problems relating the atmosphere. It could have been located in a great number of places. While there were clearly some practical considerations favoring the selection of Boulder—a university town at a relatively high elevation, close, but not too close, to a major city—the site was really chosen for its spectacular beauty.

It is a mesa on the side of one of the easternmost ranges of the Rocky Mountains. It thus affords both a vista of mountain peaks and a panorama of the town and plains below. It is a setting with strong similarities to that of the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, some 100 miles to the south.

© Architectural Record, October 1967, photo by Ezra Stoller/ESTO

The client’s program was essentially a philosophical one: it concentrated on stating what was not wanted, rather than on setting stringent requirements. The view of research facilities that emerged was of places that should be personal, idiosyncratic and possibly slightly shabby; definitely not uniform, shiny, or regimented.

Nor was there any clearly delineated series of functions that could, or should, be expressed. The type of research done generally required more thinking than concocting. The proportion of each was uncertain, however, and in any event likely to change, so that, as the servicing requirements were only moderate, there was no rationale for making a clear separation between offices and laboratories. The client did not mind if the resulting building was a confusing place to visit, as long as it was a good place to work.

In the end, the architect found that the program was philosophical because the function of the building was philosophical. It was to be a place to think, and the thinking would be done in abstruse realms along the fringes of human knowledge. Thus the forms that expressed the function must needs be philosophical as well.

Pei’s response, after considerable experimentation, was in effect to design a castle, and then remodel it into a laboratory. The castle was a response to the site and the “ivory tower” aspects of the program; the remodeling just set in motion a process of minor changes and arrangements that presumably will go on indefinitely.

© Architectural Record, October 1967, photos by National Center for Atmospheric Research

The castle keep is a two-story building at the southern end of the site which contains elements like the meeting room, library, and dining room that everyone in the complex will use, along with certain support facilities.

Individual offices and laboratories occupy the towers, which are linked to the general-use building by its site. In the towers, Pei deliberately suppresses the structural expression of the floor-to-floor height and fragments internal volumes in order to create scale-less masses that can hold their own against the surrounding mountain peaks. The hooded balconies at the top supply the place of battlements and give the towers form.

The fragmentation produced by the towers allows Pei to adjust his building to the sloping site, so that, in his words, “building and podium are one.” Fragmentation and irregular disposition of the building’s elements also ensures that the observe never sees the full extent of the complex at one time, which prevents a final judgment on the building in relation to the mountains.

© Architectural Record, October 1967, photos by Ezra Stoller/ESTO

The comparison with the Air Force Academy is instructive. There, massive walls establish a podium, on which stand rectangular buildings whose extent is clearly defined and whose structural cage is clearly expressed. Pei says that the Air Force Academy design works because the large glass areas combine into a scale-less reflecting mirror, a solution Pei was denied because of requirements for wall space and temperature control.

Actually, the Air Force Academy, from a distance, reads as an attempt to impose its geometric order on some particularly rugged scenery, while Pei’s building—on the principle of “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em”—uses an aggregate of native rock to blend with its surroundings. The towers of Pei’s building also have a scenographic effect of their own, which is particularly impressive from the masterfully designed approach road.

The two least satisfying qualities of the Atmospheric Research Center are its equivocal nature as a form and a certain disquieting thinness about some of the elements that one expects to be more massive.

© Architectural Record, October 1967

The equivocal quality is the result of the building being neither a clearly defined object in the landscape nor a self-effacing element of the landscape. It is thus probably an inescapable consequence of the way the architect approached his design. Wright’s “Falling Water,” which also is neither object nor landscape element, produces a similar effect of not quite knowing where you are; but a quality which is piquant in a house can be disturbing in a large building.

The appearance of excessive thinness occurs whenever a cross section of the concrete wall is actually exposed to view, chiefly in a number of round-arched door openings and in the overhangs at the top of the towers. The concrete wall turns out to be a stiff, sheet-like element, where the deep window recesses had led you to expect to something much more like masonry construction.

But, if the building’s vocabulary does not cover all the potentialities of modern structural materials, it still shows a highly sophisticated ability to come to terms with what modern technology can do, without producing a polemic about what technology is. In common with several other important buildings of recent years, the Atmospheric Research Center shows that it is no longer necessary to think about “Modern Architecture,” but simply about architecture. That ought to be enough.