Carlo Mollino: Architect and Storyteller celebrates the output of this multihyphenative creative

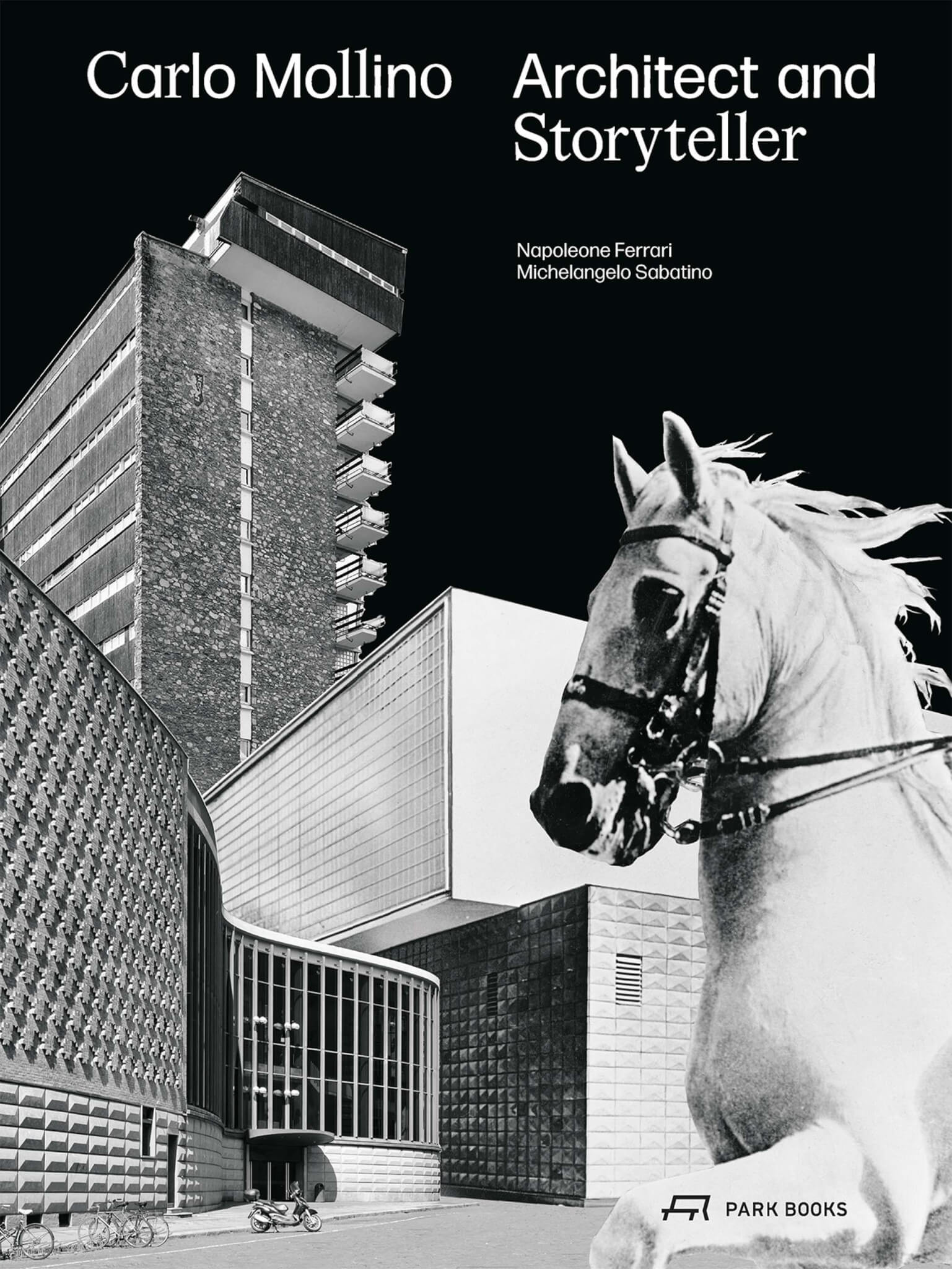

Carlo Mollino: Architect and Storyteller

Napoleone Ferrari and Michelangelo Sabatino | Park Books | $99

Having multiple outlets for one’s creativity is quite common—almost necessary—if you want to be successful today. A “multihyphenate creative” is one term to describe such an individual. Earlier, such a person might be labeled a “triple threat,” a term popularized by Hollywood in the 1970s to describe performers who can act, sing, and dance. During the first decades of the 20th century, similar people were classified as “eclectics,” a term used by artists and creatives to describe those whose work consisted of many different artistic styles and, at the time, drew inspiration from the movements of Surrealism, Expressionism, and Futurism.

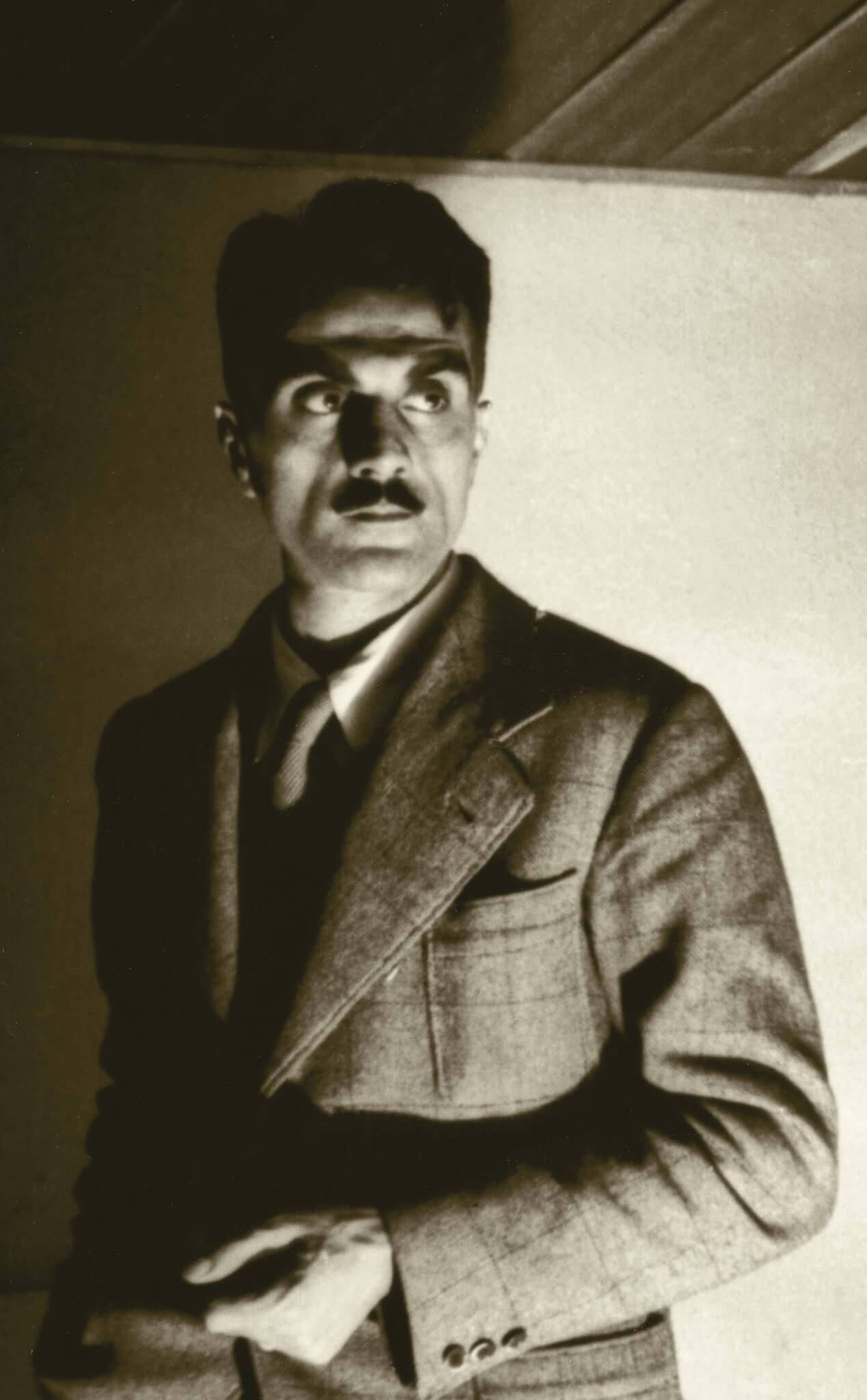

Italian architect Carlo Mollino (1905–73) was unapologetically a multihyphenate creative. A self-proclaimed “modern eclectic,” Mollino is best known today for his furniture designs and photography which you can find on display in museums and auctions houses around the world. (His collection of erotic Polaroids was discovered after his death and became influential in the fashion world.) But he also worked as an interior designer, educator, author, and architect.

The new book Carlo Mollino: Architect and Storyteller celebrates Mollino’s architectural work while documenting how Mollino used his art of storytelling to present his various views on architecture. Both authors—architect and historian Michelangelo Sabatino and author and Napoleone Ferrari, cofounder of the Museo Casa Mollino in Turin—have extensive historical knowledge of not only Mollino and his works but the wider context of architecture and design in which Mollino worked.

Ferrari and Sabatino’s book is organized in three sections: “Framing Carlo Mollino,” “Architectural Stories 1933–73,” and “Complete Works and Projects.” Theirs is the first book on Mollino that focuses on his architectural work. With thorough the use of his archive, it presents an extensive look into his creative process and the conceptualization and completion of buildings and interiors.

“Framing Carlo Mollino” establishes the basic contour of the subject’s life. Born and raised in Turin, Mollino grew up in a home full of art and books. He was encouraged to explore his interests from an early age. After college, he took a position at his father Eugenio’s business as a structural engineer. There, Mollino began to understand construction and structure, which was useful in his own creative practice. This biographical outline gives readers a complete view of who Mollino was, what drove him, and by what means he made his work.

Mollino was an active essayist and educator, so the book reproduces his texts which were featured in magazines like Stile, Domus, and L’architettura, among others. I appreciated this editorial focus, as I’ve recently been studying how fiction has influenced architects. For example: The Invention of Morel, a novel by Adolfo Bioy Casares shaped how then–creative director of Balenciaga Nicolas Ghesquière and artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster conceptualized the Balenciaga showroom, or how Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities influenced Toshiko Mori’s 1976 senior thesis at Cooper Union, “Places of Transaction,” which turned into the first Comme des Garçons showroom in the United States. In the architecture world, writing can extend your work: It’s an outlet where you are able to present your ideas and ideals to the world that you have set out to change.

Mollino was constantly writing. The authors wrote that “he understood language as a visual and spatial tool with which to explore the narrative dimensions of architecture.” In 1933, he published a four-part architecture manifesto that was published in Italian architecture and design magazine Casabella; it ran from July to November. Titled “Vita di Oberon” (“The Life of Oberon”), the text took the form of a fictional story about an architect in Turin. Calvino himself moved there after the war in 1945; the city was notably present in early stories like those in Marcovaldo, published in 1963 but not translated into English for another two decades.

“Architectural Stories 1933–73,” this book’s second section, is its main course. For likely unfamiliar eyes, the authors offer the projects that played a large role in “developing [Mollino’s] multifaceted architectural language.” These include major items like the Teatro Regio and the Torino Chamber of Commerce alongside minor works like the Torino Horse Riding Club and a chairlift station in the Alps. Beginning with “The Life of Oberon,” works are illustrated by detailed sketches and photos provided by the Carlo Mollino Archive. Notes and descriptions deepen the reader’s knowledge of each project. Photographer Pino Musi was commissioned to photograph Mollino’s surviving buildings, so these contemporary photographs give the book an exciting and updated feeling. Translations of handwritten letters Mollino penned to clients and publishers are also included; he explained his reasoning in these exchanges.

This correspondence was valuable even by itself. For instance: A letter Mollino wrote to architect and editor Gio Ponti to explain his project House on the Heights had, in Ponti’s view, such an “autobiographical energy, which would certainly have disappeared had it been treated differently.” Ponti published the letter just as Mollino wrote it in the April 1944 issue of Stile.

© Photograph Pino Musi, 2016

The third section of the book, “Complete Works and Projects”, is largely archival. It furnishes a complete list of Mollino’s architecture works and interior projects, both extant and unbuilt. Each project is accompanied with a detailed sketch by Mollino. Guy Nordenson and Sergio Pace also contributed essays which spoke about the subtle connections of Mollino’s various works and his strong and long-lasting influence on the staff and students of the Polytechnic University of Turin. To close, the authors assembled a full list of Mollino’s writings, which give leads on where to look to further understand this eccentric architect.

Carlo Mollino: Architect and Storyteller, handsomely designed by Zurich-based graphic design studio Elektrosmog, is both well-structured and large in size. It provides a much-needed overview of Mollino’s life and works. I loved this book. I recommend it to anyone interested in Mollino or, more generally, anyone who wants to learn more about how a successful multihyphenate navigated the world.

Josh Itiola is designer and writer based in New York City.