Architectural Herstory: 6 Designers Who Paved the Method for Girls in Structure At present

Browse the Architizer Jobs Board and apply for architecture and design positions at some of the world’s best firms. Click here to sign up for our Jobs Newsletter.

If history has taught us anything, it is that a driven woman is a force to be reckoned with. Georgia O’Keeffe, Mary Cassatt, Miriam Makeba, Harper Lee, Rukmini Devi Arundale, Frida Kahlo — the list of the talented creative woman who played a vital part in creative culture goes on and on. Yet, unfortunately, architectural history has not been kind to the creative women who have shaped it, often assigning their achievements to male counterparts or erasing them altogether. For centuries, women of all ages, backgrounds, countries and professions have persevered by challenging inequality, questioning bias.

Today, gender inequality operates differently, as women are no longer excluded from the profession. Yet, as the number of female students in architecture programs continues rising towards parity, just 25% of working architects in the United States identify as women. (Comparatively, 36% of lawyers and 41% of physicians and surgeons are women.) Meanwhile, awards lists and firm leadership positions continue to be male-dominated.

As in many industries, the history of architecture is one that has largely been written from a male’s perspective; younger women do not have a canon of historic figures — such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn — whose achievements they can strive towards. International Women’s Day offers a platform to dig into history and to celebrates the lesser-known pioneers who paved the way for female architects today. By telling their stories and shining light on their achievements — made in moments when women weren’t invited to the drawing table as they are today — can inspire women to seek leadership positions and instruct both genders about the evolving trajectory of equality in the industry.

Katherine Briçonnet (1494–1526)

Château de Chenonceau by Katherine Briçonnet, Chenonceaux, France Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Known for her role as the daughter of a nobleman and the wife of an architect as so many women were in her day, Katherine Briçonnet’s importance in the architectural history books was forgotten for centuries. She played a significant role in designing the famous Château de Chenonceau in France’s Loire Valley during a time when her husband, Thomas Bohier, was away fighting the Italian war.

Madame Briçonnet oversaw much of the architectural decisions at a time when women were often denied a proper education and rarely played active roles in shaping arts and culture. Today the chateau has a rich history influenced by a long line of women who have lived, worked and owned the property over the years — the chateau is fondly nicknamed Le Château des Dames.

Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham (1632–1705)

Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham and Weston Park, Staffordshire, England | Photos via Wikimedia Commons

Often dubbed the UK’s first female architect, Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham was a prominent designer of grand houses when women weren’t legally allowed to study or practice architecture. While there are still many historians who like to debate her role, historian John Millar has dedicated more than 50 years of research to Lady Wilbraham and her achievements.

Unfortunately, because the majority of her contributions were historically attributed to her husband, Millar’s notions are still relatively speculative. Millar argues that although Thomas Wilbraham used male assistants to supervise his projects, Elizabeth Wilbraham was most likely behind the formal designs of more than 400 buildings. What is more, she is even credited with tutoring Sir Christopher Wren, a highly acclaimed English architect of the time.

Marion Mahony Griffin (1871 – 1961)

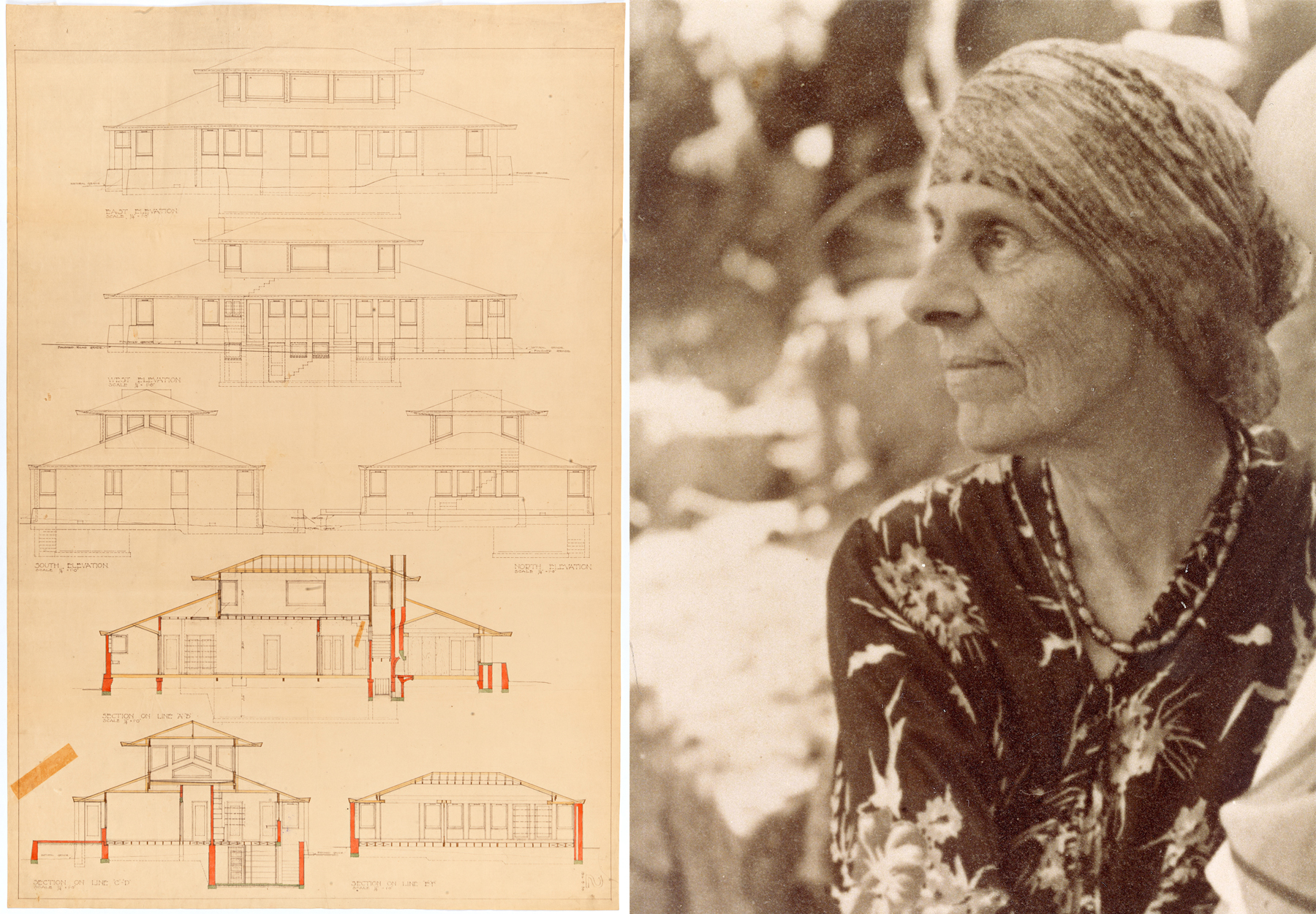

Design for Suburban Residence Exhibit Plan 2 by Marion M. Griffin. Image from the National Archives of Australia

An adventurous visionary, Marion Mahony Griffin was a woman ahead of her time. Over five decades, she promoted progressive ideas that are as relevant today as they were then. Mahony Griffin was one of the world’s earliest licensed female architects. She studied architecture at MIT and graduated in 1894. She was the first employee of Frank Lloyd Wright, working with him in his Chicago office from 1895 to 1909, a period coinciding with Wright’s most intensely creative years.

Many of her signature fine line renderings were included in the Wasmuth portfolio, published in Berlin in 1910. It is now regarded as one of the most influential architectural publications of the 20th century. Unfortunately, like many of his counterparts, Wright was renowned for his reluctance to acknowledge the talents of his staff, and Mahony’s monogram appears on only a few of the 50 or so plates she contributed. Today she is thankfully being acknowledged in her own right with many historians dedicated to uncovering the extent of her impressive contribution to architecture.

Lilly Reich (1885 – 1947)

Lilly Reich, Photo vis Wikipedia, and Barcelona Chair, Image by Knoll

There are two main categories when discussing women in architecture who have not received the credit they deserve. Those who history forgot to mention, typically by associating their work with someone else (a man) and those whose work is widely celebrated but their contribution is overshadowed by their male collaborator’s legacy. Lilly Reich falls into the latter camp.

While you occasionally see Reich’s name in small print in the footnotes of copy about Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as the designer of instantly recognizable furniture pieces such as the Barcelona chair, the Brno chair and the Weißenhof chair, more often than not, she goes entirely unmentioned. Meanwhile, many historians have formed compelling arguments to suggest that Reich was, in fact, the engineer of many of the ideas that shaped these pivotal works. Some even offer that the Barcelona couch — still sold by Knoll, who credits the design to Mies van der Rohe — was dreamed up by Reich.

Minnette de Silva (1918 – 1998)

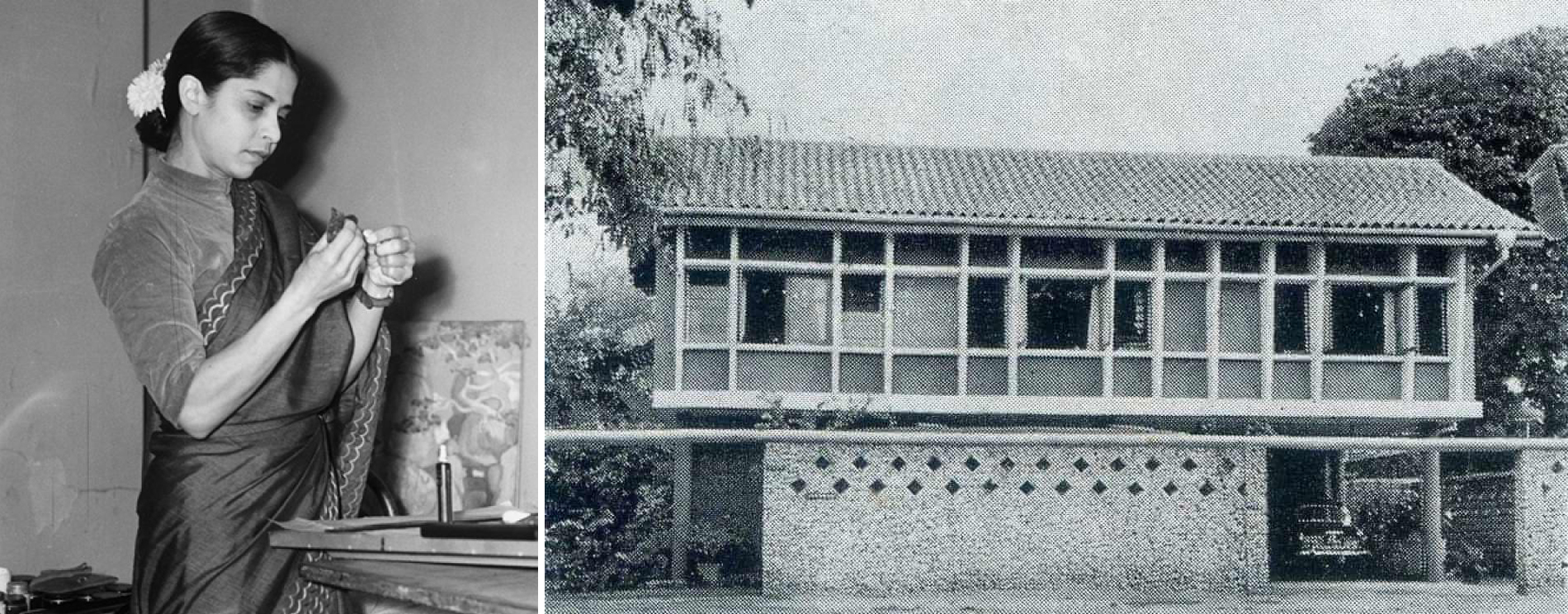

Minnette de Silva and her house for Ian Pieris, Alfred House Gardens, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Photograph by LASWA

Minnette de Silva was an architect whose life and work were so pivotal and pioneering that we must ask: how she did she go so largely unnoticed for decades? Born in Kandy, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1918, she had many firsts to her name: first Sri Lankan woman to be trained as an architect; first woman to establish her own practice — called the Studio of Modern Architecture — in the country; first Asian woman to be elected an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects (in 1948); and the first woman to be awarded the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects gold medal (in 1996).

Although born into a wealthy family, she was concerned with more than just building houses for her friends. Her attempt to fuse artisanal traditions with her modernist buildings ensured that often impoverished craftspeople could earn a living from their work, forging a unique and memorable aesthetic in the process. She was a remarkable designer, a free thinker and Sri Lanka’s first modernist architect. Unfortunately, of the countless projects de Silva once designed, including her personal studio, many are now in a state of abandonment while others have been destroyed entirely to make room for luxury lots and skyscrapers that dominate the city, leading to her name being vastly forgotten.

Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926 – 2012)

The Pacific Design Center by Norma Merrick Sklarek, West Hollywood, CA, United States Photograph by Robert Landau

Being the youngest on our list, you’d be forgiven for thinking that working in architecture should have been easier for Norma Merrick Sklarek. You’d be wrong. Norma Merrick Sklarek was a Black woman living in America. Something that, even today, a century on, is an endless challenge. Norma Merrick Sklarek was the first Black woman to graduate from Columbia University School of Architecture in 1950, the first to become a licensed architect in the state of New York in 1954, then in California in 1962, the first Black woman member of the AIA in 1959 (and later named a Fellow in 1980). As a credit to her tenacious character, when issued with her license, she was quoted as saying, “As far as I know, I am the first and only Black woman architect licensed in California. I am not proud to be a unique statistic, but embarrassed by our system which has caused my dubious distinction.”

Sklarek used her professional and academic position throughout her career to teach and mentor other minorities in the architecture field. She strove to be an example for others and be the role model she never had. Two Black women had come before Sklarek, yet she was unaware of their existence. Beverly Loraine Greene was the first Black woman to become a licensed architect in the United States in 1942, and Louise Harris Brown was the second in 1944. The historical lack of inclusion that resulted in Sklarek’s not knowing these two women speaks to the importance of telling Sklarek’s story.

The list of female architects and designers who paved the way for our successes is long and inspiring; Julia Morgan, Eileen Gray, Charlotte Perriand, Jane Drew, Lina Bo Bardi, Anne Tyng, Denise Scott Brown are but a few of the other exceptional women whose work has shaped our towns, our cities and our lives.

Browse the Architizer Jobs Board and apply for architecture and design positions at some of the world’s best firms. Click here to sign up for our Jobs Newsletter.