AN speaks with Bruce Mau about a new film on his work and why he has hope for the future

Mau is a documentary film by Benji and Jono Bergmann about Bruce Mau. While the movie traces Mau’s life from his childhood in a Canadian mining town to his current exalted status as a global design guru, it prompts as many questions as it answers. After a screening, AN met with Mau to discuss his legacy and what design can do in the face of the world’s seemingly insurmountable problems. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

AN: I’d like to start by talking about S,M,L,XL. It’s mentioned in the film that the book changed the idea of the architecture monograph forever, but it seems that very few books have followed in its footsteps. Could you talk about how the book developed and how you see its legacy?

Bruce Mau: The objective was to get at the reality of architectural practice. I felt like when I looked at architectural publishing, it had almost no relationship to [architecture’s] very intense engagement with the real world. All that stuff got sanitized and washed away and you ended with these perfect objects that seemed to pop into the world fully formed, as if nothing complex ever happened. They didn’t include the full bandwidth of life. What we tried to do is say, “Look, let’s actually do something that really conveys the visceral experience in a very documentary-like way.”

We developed a methodology. We would take all the existing material and all the published versions and go through it all and get a sense for ourselves what it was. And then [coauthor Rem Koolhaas] would take us through the project and tell us how it was conceived. From there, we would develop a concept of what the real presentation out to be. In some cases, that meant creating new things to tell the story, or it just needed to be compressed in some way.

One of the things we added in the book is what we call “world images” that were put in whenever the book got too stable. Whenever the book seemed to have a kind of cadence that was somewhat predictable, we would insert a completely random world event that would turn the book 90 degrees.

I think that one of the reasons that [S,M,L,XL] hasn’t been replicated—it was copied a lot in terms of its form, right? People did chop down a lot of trees, and I feel guilty, but they didn’t actually do the process—because the process is really hard. It took us five years and nearly bankrupted both of us. But it was an incredible experience. I practically did a PhD in architecture with Rem, and we traveled to almost every project. It was a wonderful time.

You say in the film that “design is one of the world’s most powerful forces.” And yet the film also tells stories of how design can be interrupted or undermined by the sort of “world events” you included in S,M,L,XL. For example, the film shows the trouble you ran into designing a new plan for Mecca as a non-Muslim and how China shut down the Massive Action exhibit due to a squabble with Canada.

In the film there’s a sense that we didn’t succeed in Mecca. But I think you have to understand that success is a nuanced entity. With that kind of work, it’s like carving Jell-O with a chain saw. You can’t go for the details, which is anathema to designers as a group. We’re control freaks. I’ve studied the I Ching and Buddhism and John Cage and the whole idea of allowing evolutionary forces in the world and getting out of the way of yourself. You do your work and have your intent, but also know that sometimes it’s best to do nothing.

I think of the Mecca project as wildly successful because it introduced a different way of thinking. We weren’t in control—I wasn’t building the city. The real project is to introduce a vision, a conversation, and help people think about it. That’s the work. After that project, [Saudi Arabia] commissioned us to lead the vision for a post–oil-economy city. That wouldn’t have happened if we weren’t successful [with Mecca].

Do you have any updates on Massive Action?

Yes, we’re very excited to be working [on Massive Action] with the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia.

You mentioned how the biggest difference between Massive Action and Massive Change is that with Massive Action, you want to provide tools for those who visit the space. Can you go more into detail about what these tools could be?

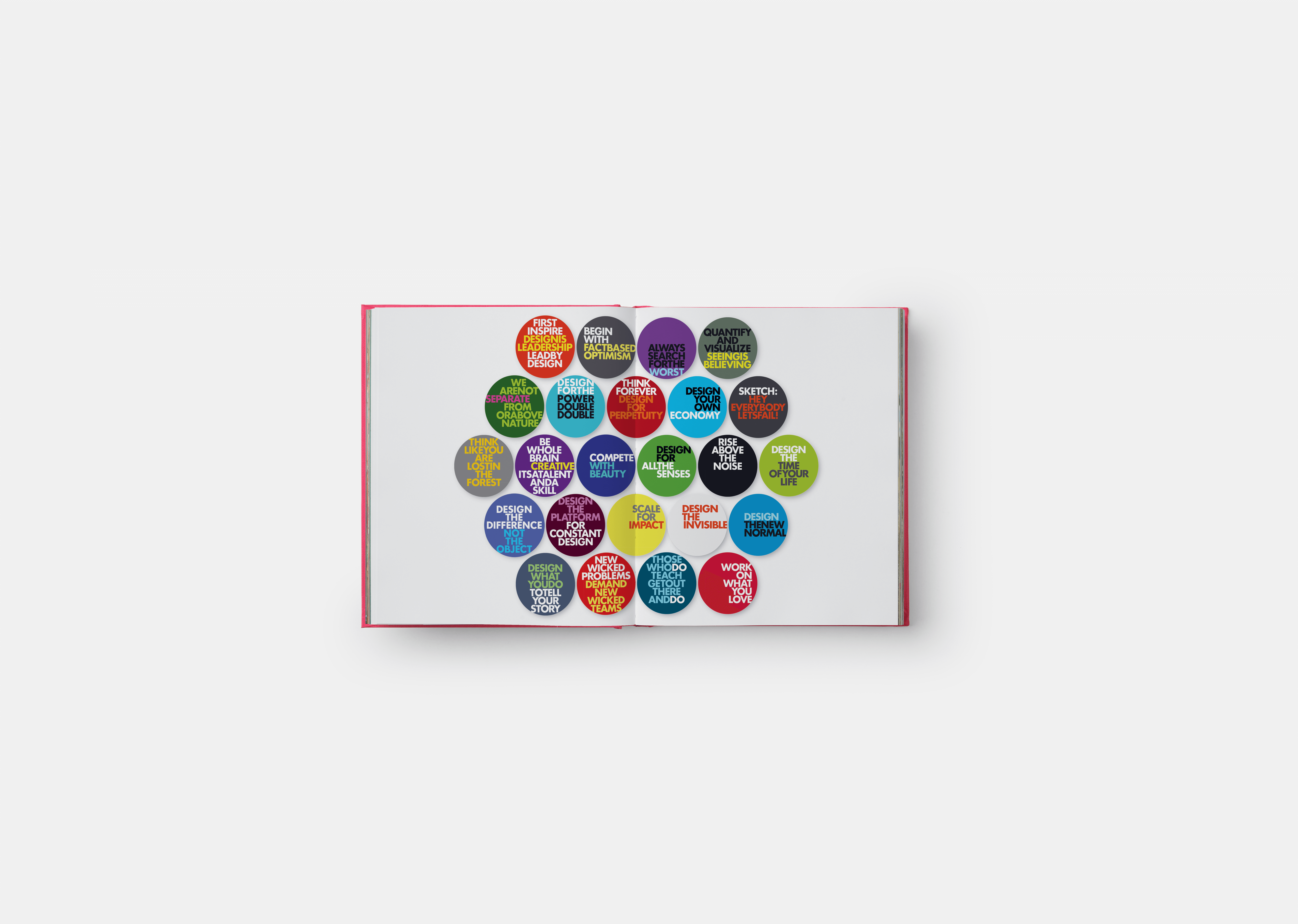

The MC24 book is the tool kit. When we did Massive Change, we didn’t have that. So how do we create that experience for people coming into a space? It’s an interesting problem because the model of experience in a museum is consumption, and what we’re asking for is production.

As a designer, I realized that there’s a very interesting class difference that has emerged—the two classes of producers and consumers. The producer class can produce the world and manipulate it according to their desires and ambitions. The consumer class define their lives by choosing things. I think that helping people understand the power that they have and giving them the tools to say, “I can design my life, I can design my work, I can design the way that I live,” ultimately [will give] people ways of recovering optimism and the capacity to think differently about what’s going to happen and their role in it.

In the Q&A after the film, Bjarke Ingels said that democracy itself is in crisis. In response you said that it’s “kind of easy to lose it and hard to recover. I would encourage everyone to do anything they can to reinforce it.” Do you think we might lose it? Is there a design solution?

I don’t think it is hard to imagine that we could lose [democracy] in America. Look at history. There’s no guarantee in culture. Just because you’ve accomplished something does not [mean] it’s a blank check for perpetuity. You have to constantly reinvest and reinvent and find new forms and relevance in order to sustain things.

The challenge of democracy is that if you don’t educate people, you create a situation that is ripe for autocracy. We’re at a point where only 37 percent of Americans have degrees in higher education. It’s a shockingly low number, [especially] in a time when access to possibility is so connected to having the ability to engage higher-order complexity. We began a long-term engagement with education as one of our key areas of focus. We worked on a book called The Third Teacher, which looked at the built environment as a teacher and studied how we build our schools and what is the story being told to children. If we look at that story, in a lot of places, it’s not a story that we would want our children to hear. So we broke it down and said, “Look, there are 79 ways that you can use the built environment as a teacher.”

There’s been a lot of discussion in architecture about the culture of work and a lot of pushback from the younger generation against principals who want them to work all the time. What is your view on this?

I’m with the students! I think the way that we’ve conceived of work is so impoverished. It’s really awful. So, no kidding people don’t want to do it. It’s not surprising at all. It’s amazing they’ve done it as long as they have.

There’s this old-fashioned notion that we have to pound these people to the dust—like that’s tougher and better. It’s just nonsense. You’re losing money, resources, and talent by overworking people. You put so much effort into getting the right people and then you’re grinding them into the ground. We have to think differently.