Adjaye Associates designs exhibition that celebrates Jean-Michel Basquiat’s vibrant life

Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure

601 West 26th Street, New York

Open indefinitely

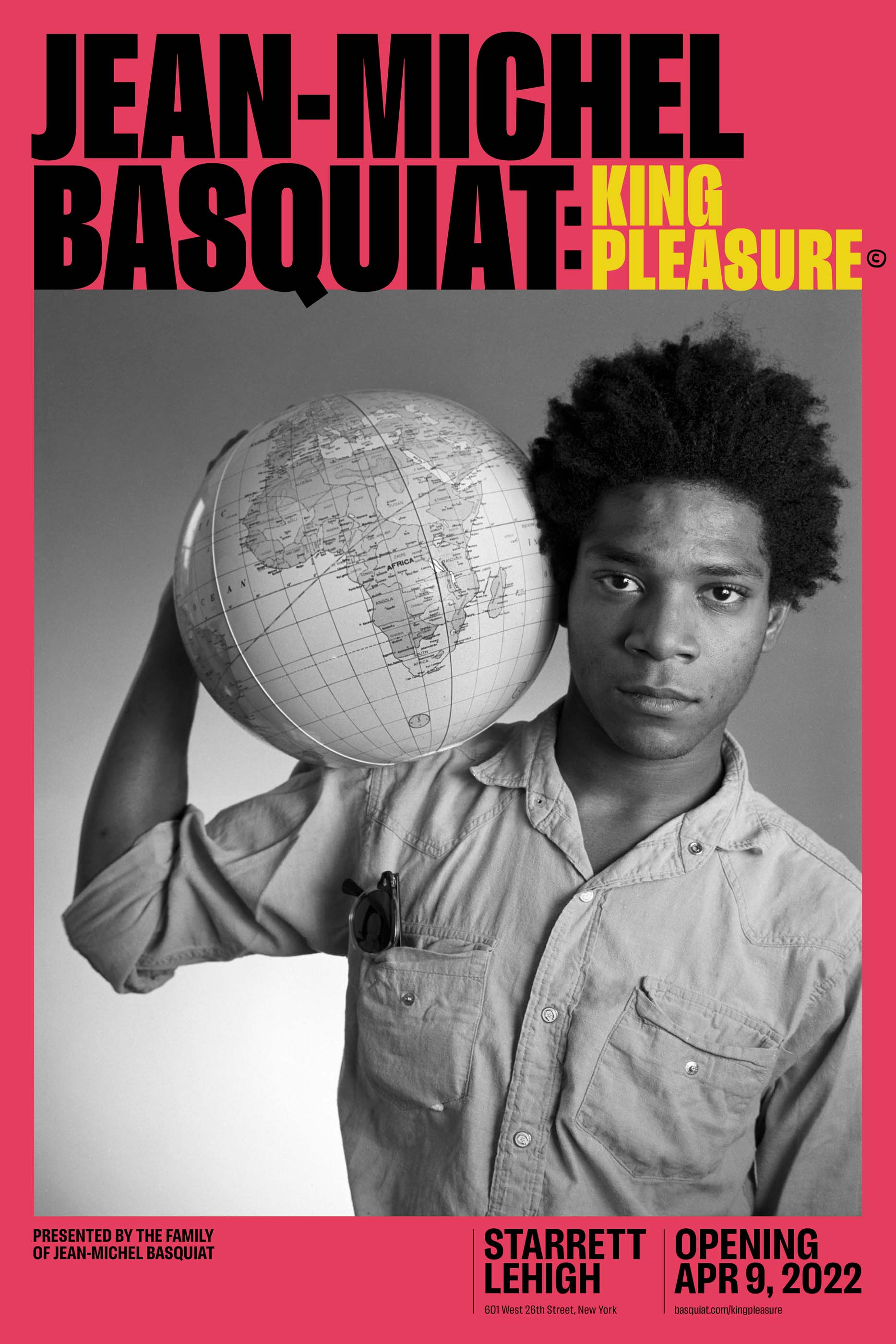

To begin experiencing Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure even before I set foot in the Starrett-Lehigh Building in New York’s Chelsea district, I queued up “Listen Like Basquiat: Childhood,” one of four Spotify playlists curated to accompany the exhibit. The voices of Lena Horne and Dinah Washington buoy me on what’s otherwise an oppressively hot day. When I arrived, I was greeted by a recording of Jean-Michel reading from the Book of Genesis, along with a number of portraits from various stages of his life.

Taken together, the exhibition feels less like a retrospective and more like a family photo collection. This declaration doesn’t denigrate the work of curation that the exhibition entailed—namely, the staging of over 200 paintings, drawings, ephemera, and artifacts meticulously staged to recreate Basquiat’s childhood brownstone in Brooklyn (where he was born in 1960) his studio on Great Jones Street (where he died in 1988). This makes sense: Though Jean-Michel’s father Gerard was the administrator of his son’s estate until his death in 2013, his sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux, now direct their brother’s legacy. They, alongside stepmother Nora Fitzpatrick and their children, curated the environments that comprise the 12,000-square-foot exhibition.

The staging reminded me of words from bell hooks’s essay “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life”: “To enter Black homes in my childhood was to enter a world that valued the visual, that asserted our collective will to participate in a noninstitutionalized curatorial process. For Black folks constructing our identities within the culture of apartheid, these walls were essential to the process of decolonization. In opposition to colonizing socialization, internalized racism, these walls announced our visual complexity.” In King Pleasure, I was immersed in the familial context, lineage, and visual world that affirmed Jean-Michel’s Blackness and shaped him as an artist.

In service of this vision, the exhibition design by Adjaye Associates offers a refreshing solution, eschewing the white-wall gallery experience in favor of a layout of 2-foot-wide nail-laminated timber panels. Early meetings with the family were a collaborative process of establishing a material vocabulary that would speak to each section of Basquiat’s life; the wood stain coordinates with the sections of the show, reinforcing the narrative framing which takes viewers through each biographical chapter. Additionally, the apparatus is modular, so the staging could travel for future iterations of the show.

The show generates intimacy with a legendary artist. When I heard Marc McQuade, associate principal at Adjaye Associates, speak about the feeling of first stepping into the Basquiat family’s Brooklyn brownstone or seeing Jean-Michel’s bicycle at the warehouse amidst his paintings, a certain archival fever took hold. I saw it in McQuade’s eyes when he recounted the weighted joy that Lisane, Jeanine, and Nora felt as they unearthed objects, dusting off each to reveal a childhood memory. Their care, matched with the designers’ skill, avoids the “Disneyification” of Jean-Michel’s life.

Though the paintings themselves are, of course breathtaking, my breath was also taken away by Adjaye Associates’ recreation of two spaces: the Brooklyn brownstone and studio on Great Jones. While walking through the restaging of the family’s dining room, I had a moment of recognition. Something about the china cabinet and the floral-patterned wallpaper takes me back to the house my mother grew up in in Alabama—these finishes could be from any middle-class Black family’s midcentury home anywhere. In the studio, the team’s eye for detail is immaculate—cigarettes, with the time-appropriate packaging design, litter the floor; his boombox and turntable occupy places of honor; Basquiat’s own footprints mark the sketches; and the LED lighting that illuminates paintings elsewhere are replaced with spotlights like those Jean-Michel would have used. There’s something so intimate about this light to me: Eschewing “museum-quality” illumination for the real thing is a simple but profound gesture.

My favorite room in the exhibition is the last one. “Light Night NYC” recreates the Palladium nightclub, where Basquiat’s murals were featured in the VIP room and behind the bar. (The club, operated by Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, featured an interior designed by Arata Isozaki.) 1980s disco and new wave blasts, and a video wall displaying nightclub scenes from Jean-Michel’s life anchors the space. It’s a reminder of the vibrancy of his life, lived among people, celebratory and in motion. The room realizes Jeanine’s desire “to have a show that all people want to experience. We want them to see Jean-Michel in themselves, an artist that looks like them. We want it to be completely accessible for those who have felt intimidated in the past by going to a museum.”

While this was certainly how I felt experiencing the show, I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that the show’s steep price point makes it harder for anyone in New York City on an artist’s budget to attend—those who, like Jean-Michel, don’t want to go home until they’ve made it. Still, I left the exhibition energized with the help of Donna Summer. Jean-Michel’s light burned bright during his 28 years. For those of us still here, the scenes in King Pleasure spur us into action. There’s still so much to do.

Irene Vázquez is a poet, journalist, and editor based in Hoboken, New Jersey.