a look at italian visionary andrea branzi’s pioneering early career

andrea branzi: breaking the mold

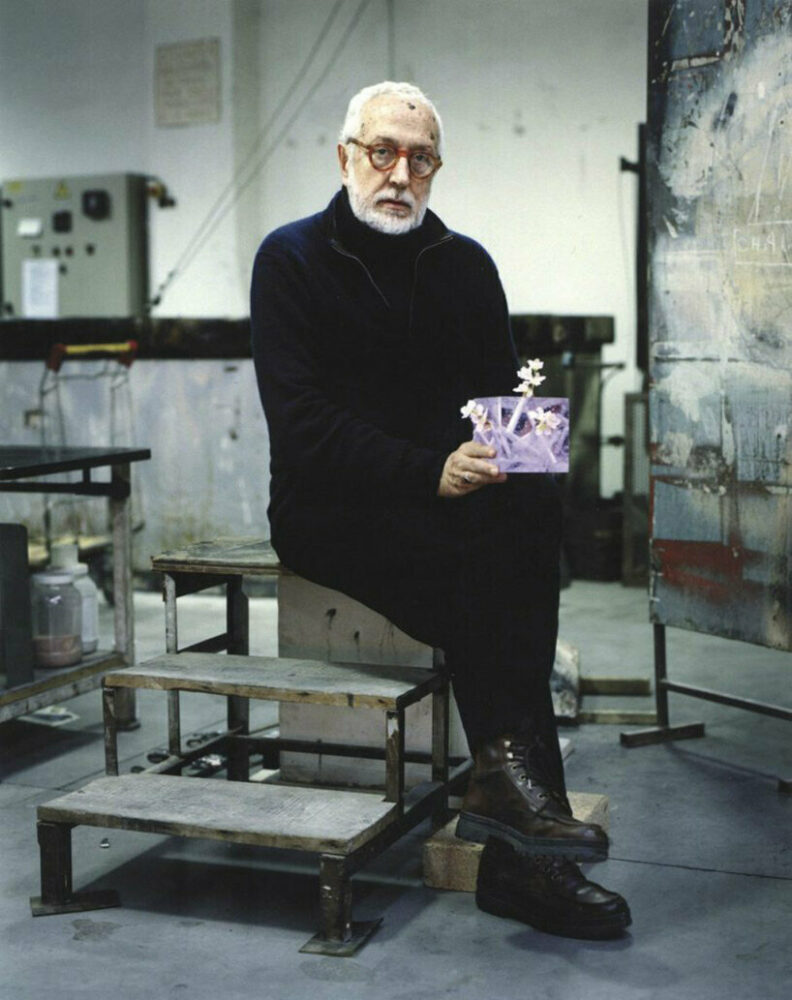

Italian architect, designer, and theoretician Andrea Branzi was never interested in understanding the differences between design and art. Instead, he turned his focus to creating objects with narratives instilled both by him and whoever interacts with his works. With a long and significant involvement in the discussion about cities, architecture, and design, and a career spanning over six decades, Branzi has undertaken projects involving the relationship between people and objects and the way we navigate the world, anticipating problems we currently face.

Born in Florence in 1938, Branzi graduated from the University of Florence in 1966, where he met fellow students that would soon become his colleagues. At that time, the Radical Design movement was burgeoning in Italy, peaking in the 70s and grappling with control over the environment by challenging the status quo. Futuristic, expansive, and widely experimental, this groundbreaking school of thought explored how technology and design can reshape the future by developing new ways of inhabiting the planet. The concepts emerging from this period are still part of our agenda today.

Andrea Branzi, an Italian visionary | image © Cirva Kai Juenemann

pioneering radical design thinking

In line with the movement, Andrea Branzi founded the Italian avant-garde group Archizoom Associati in 1966, together with Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello, and Massimo Morozzi. Its radical approach to architecture reacted against modernism and downplayed practical concerns in favor of an imaginative, science-fiction-like attitude.

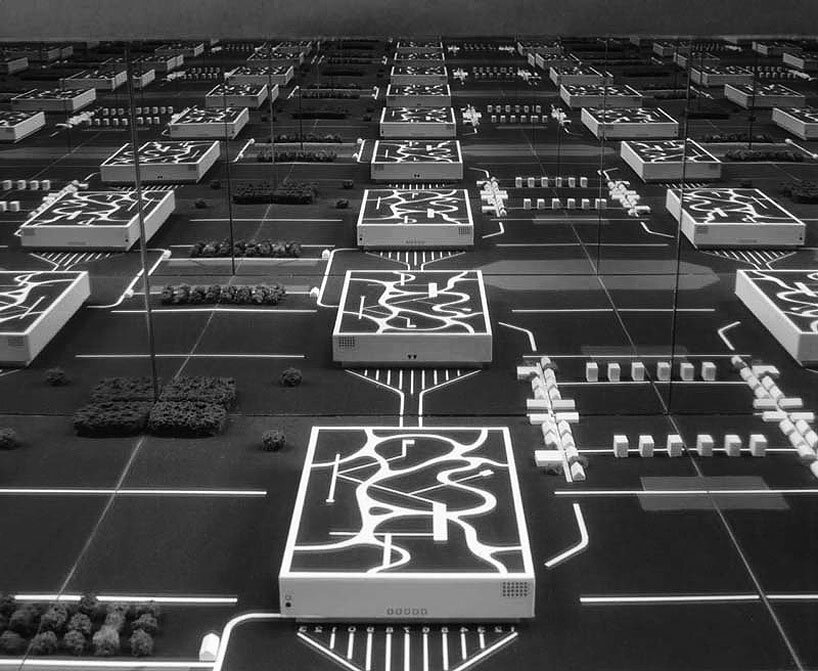

The most critical work that surged under this group was the ‘No-Stop City,’ an unbuilt project presenting an urban utopia where the architectural form disappears and only the essential remains. In questioning the character of existing cities, the proposal envisioned a metropolis with repetitive patterns and multiple hubs, within which individuals would have a large degree of freedom to build. Moreover, the site is imagined to extend infinitely by adding homogeneous elements adapted to various uses. Ultimately, the project demonstrates the consequences of late-capitalism urban development.

Archizoom Associati founded in 1966 | image courtesy of Friedman Benda

‘A project that was of great importance for me, but also for my generation, for many artists that came afterwards was the ‘no stop city’ project,’ Branzi told designboom in 2003. ‘A fluid metropolis, where even the concept of modernity within order changes towards an idea of uncontrollable complexity and a world destined to a huge diversification. Today I see that this type of scenario is appreciated, shared by famous contemporary architects who recognize the radical movement and the ‘No-Stop City’ project to be a genetic event, which intercepted a development in the culture of the project, becoming an example within the project itself.’

‘No-Stop City’ (1970) by Archizoom Associati

In 1976, Andrea Branzi took part in the post-radical avant-garde group Alchimia, founded by Alessandro Guerriero, before being associated with Ettore Sottsass’ Memphis Group in the 1980s. He also co-founded Global Tools in 1974 — a multidisciplinary counter-school design teaching program that promoted experimental concepts and strategies, relying on irony and provocation and aiming to dismantle the traditional principles and applications of architecture, urbanism, and design. According to Branzi, ‘rather than design human environments embodying unattainable ideals and goals, radical architects’ utopian projects exposed and examined the contradictions of the architectural discipline and existing society.’

A few years later, in 1983, he co-founded the Domus Academy — the first international post-graduate school of design where he was the cultural director, vice-president, and coordinator. Today, he lives and works in Milan, where he continues to explore the fields of industrial design and research design, architecture, urban planning, education, and cultural promotion; his artistic approach boasts an attempt to connect the industrial world to the poetry of nature. He is also a freelance writer and has been featured in major publications, including several volumes with the MIT press.

‘Domestic Animals’ bench (1985) by Andrea & Nicoletta Branzi | image courtesy of Wright

an award-winning catalog of works

Among his most famous furniture designs are the ‘Superonda’ sofa (1966), ‘Mies’ chair (1968), and the modular ‘Safari’ sofa (1968), all of them intending to question the rules of how we live. In the 1980s, he created ‘Domestic Animals,’ a peculiar collection that explores Neoprimitive aesthetics where nature and artificiality converge. Designed alongside Nicoletta Branzi, the project reveals a series of ‘creature objects’ boasting raw pieces of trees embedded into sleek, minimalist, and gray-scaled extensions of tables, chairs, and benches. Since the turn of the millennium, Branzi’s designs have developed into personal objects of a more fragmented composition, filled with subtle Yiddish irony.

Branzi has received several awards throughout his career, including three Compasso d’Oro, honored for individual or group effort in 1979, 1987 and 1995. His work has been showcased in the Venice Biennale, at Milan’s Triennale Design Museum, and at New York’s MoMA, among others. In 2008, the Italian visionary was named an honorary Royal Designer in the United Kingdom and was the receptor of an honorary degree from Sapienza University in Rome. That same year, his work was featured in an installation at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. His works are held in the permanent collections of the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; the Victoria And Albert Museum, London; the Museum Of Fine Arts, Houston; the Israel Museum, Jerusalem; and the Museum Of Modern Art, New York, among others.

‘Safari’ sofa (1967) by Archizoom Associati | image courtesy of Poltronova