A Forensic Architecture exhibition in Germany uses real life narratives and architecture to document violence and systemic racism

Three Doors

Frankfurter Kunstverein

Markt 44, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Open through September 11

On May 24, a gunman entered Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, and killed 19 children and two teachers before being shot by off-duty Border Patrol officers. For nearly an hour, police massed in the hallway while the shooter murdered his victims. According to latest reports, the classroom door was never locked; contrary to initial police testimony, they could have entered the classroom at any time. The only thing separating the police from the shooter was a single, unlocked door.

An initial response to the shooting was Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s push to “harden” schools, extending an enterprise that began after the 2018 shooting at a high school near Houston. In Abbott’s School and Firearm Safety Action Plan, doors form a key part of this hardening: “the Legislature should consider […] the potential use of metal detectors or deadbolt locks for certain doors, and greater control of entrances, exits, and external access.” This plan sees doors as the key node that can transform schools from “soft targets” to “hard” ones where entry and egress can be controlled.

Public health experts and architects pushed back against the idea of hardening as a solution to school shootings. On Twitter, architecture critic Paul Goldberger described the idea of single-entry schools as “lunacy,” while researchers confirmed that hardening “doesn’t work.” The Uvalde school district itself received a $100 million grant to increase physical security in 2020, which failed to prevent the shooting. Clearly, doors are not a solution to school shootings. We cannot “harden” the whole world, nor can we design our way out of shootings. So how might architecture meaningfully engage with such tragedies?

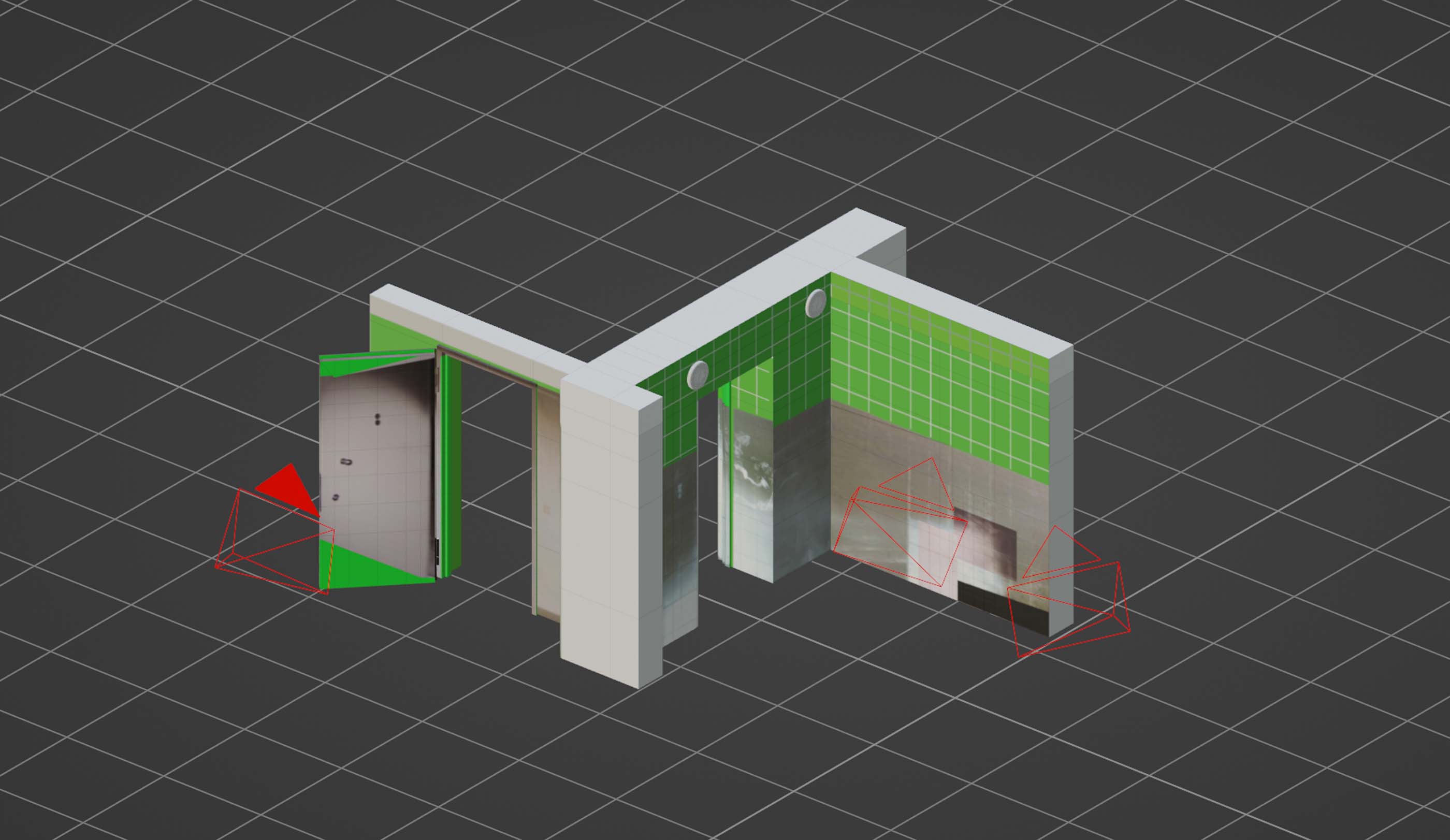

Doors figure prominently in Forensic Architecture’s (FA) new exhibition Three Doors, on view at the Frankfurter Kunstverein (FKV) and created with FA’s sister agency FORENSIS in Berlin. Since 2010, FA has developed a repertoire of spatial techniques—including GIS mapping, 3D modelmaking, auditory sampling, and critical writing—with which to analyze and exhibit human rights abuses. Through timelines, filmed interviews, and spatial reconstructions, Three Doors musters a huge and harrowing body of evidence to point to systemic racism and policing failures. While the detailed incidents occurred in Germany, the show offers a way for architectural tools to be useful when responding to violence wherever it occurs—through an engagement with the very spatial specifics of those places.]

Two of the exhibit’s titular doors relate to the February 19, 2020, mass shooting in Hanau, Hessen, committed by a far-right extremist who targeted people of color. The first door is the locked emergency exit of the Arena Bar in Hanau, where two victims were murdered. The second is the front door of the perpetrator’s house, which was known to police but not surveilled until after the killing spree.

The police response to the murders in Hanau was incomplete at best and criminally negligent at worst. On the night of the shooting, victim Vili Viorel-Păun gave chase as the shooter drove from Hanau’s Heumarkt, where he had murdered three people, to Kurt Schumacher Square, where he killed six others. Viorel-Păun contacted police three times; all of his calls went unanswered before the shooter killed him through his car window. After the attack, police failed to inform victims’ families of the deaths of their loved ones; harassed families; and referred to victims using racist epithets. The understaffed police emergency number Viorel-Păun called was only belatedly acknowledged, and an official investigation hastily concluded that all police officers acted appropriately. It was later found that 13 on-duty officers that night were members of a racist far-right group chat. The “Initiative 19. Februar Hanau” was founded by friends and family members of victims following the shooting; the group and the lawyers of Gökhan Gültekin, one of the victims, commissioned FA and FORENSIS to investigate the case.

At FKV, videos and timelines form the basis of the display on Hanau. One room contains FA’s digital reconstructions of the shooting, while a detailed timeline of the evening runs down a long wall. In another room, video interviews with family members of the victims play on central screens, while a post-shooting “Timeline of Collective Action” stretches down a wall. The combination of elements displayed—detailing specifics of the shooting and survivors’ and activists’ efforts to challenge official inaction and dissimulation—fuels a fury in visitors. We ask ourselves: How could such a thing happen? And then we are shown exactly how it could.

The exhibition’s third door leads to a jail cell in the Dessau police station where Oury Jalloh died on January 7, 2005. After arresting him, police cuffed Jalloh, a Black immigrant, to a fireproof mattress in a cell. Shortly thereafter, a fire broke out in his cell. By the time it was extinguished, half an hour later, his body was burned beyond recognition.

According to Dessau Police, Jalloh set the fire himself using a lighter. This narrative, however, was soon called into question, launching a series of private investigations and public protests. These investigations uncovered a string of imprecisions and conflicts in official accounts, and three particularly damning pieces of evidence. First, separate private autopsies found that Jalloh’s nose, rib, and skull had been broken. Second, the supposed lighter Jalloh used bore no traces of his DNA. Third, the intensity of fire necessary to burn the cell and a human body to the extent of what happened requires a large amount of accelerants; in other words, the fire was lit by someone else. The investigations convincingly show that Dessau Police either burned Jalloh alive or first beat him to death and then burned his body to cover their tracks.

After public outcry, two police officers were tried for murder; they were both acquitted, after what the Initiative in Memory of Oury Jalloh describes as an insufficient legal process (one was later found guilty of involuntary manslaughter and fined €10,800). In 2020, the Initiative asked Forensic Architecture to study Jalloh’s case. FA constructed digital and physical models of Jalloh’s cell and found that the smoke marks on the inside of the door matched those found in the corridor outside the cell, rather than the cell’s walls themselves, supporting the conclusion that the fire was set by police officers who opened the door to the cell after starting the fire.

At FKV, the display on Jalloh largely consists of FA’s reconstruction of the cell accompanied by footage recounting the investigations. The display isn’t spectacular; it doesn’t have to be. The presented facts are a damning indictment of the police’s racism and brutality toward Jalloh.

Three Doors also presents FA’s work around the world, including a study of the “Death Alley” of petroleum refineries in Louisiana, a textbook example of environmental racism. Through this project, FA investigates another register of racist violence, one that acts not through weapons but through pollution and land use. In linking different categories of violence, FA points out that racism is systemic and varied in its manifestations and that we must look to activism and civil society to expose, understand, and display these cases.

The type of police and state incompetence and lies demonstrated in Uvalde lead, rightly, to a revulsion against institutional responses to violence. Three Doors showcases FA’s alternative approach, which, as the FKV website states, emerges from “a coalition of civil society actors, and as a counter-investigation to those investigations led and answered for by authorities or the state.” Architecture, through its ability to visualize space, is part of a toolkit that can help us understand violent acts and, by providing a counter-narrative, address their horrifying yet numbing monotony. Three Doors’s power lies in its combination of empathy and investigation—of painstaking reconstructions and a focus on the victims and the people who have fought to keep their memory alive. FA uses architecture not as an end but as a means to tell these stories in their shocking and tragic fullness.

Doors opened and not opened; doors behind which police waited; and doors behind which evidence disappears: Three Doors makes clear that the doors to justice and transparency all too frequently only swing open when survivors, community members, and activists protest and organize, vocally and strategically, to create loud alternatives to official narratives.

Alexander Luckmann is an MA/PhD student in the history of art and architecture at UC Santa Barbara. He studies historic preservation and modern and contemporary religious architecture, with a focus on Germany.