A Centuries-old Japanese Farmhouse Finds a Home Outside Boston

The back of a 1980s colonial-style residence in suburban Boston might sound like an incongruous location for a centuries-old traditional Japanese house, or minka. Nevertheless, in the bedroom community of Belmont, Massachusetts, a nearly 300-year-old farmhouse—complete with a steeply pitched roof and a rough-hewn frame held together with mortise-and-tenon joints—has been moved there from a village northeast of Kyoto and erected as an addition to an otherwise unremarkable American house.

The minka’s relocation, a complex international effort spanning many years, is the passion project of Peter Grilli, president emeritus of the Japan Society of Boston and an expert on Japanese history and culture. Raised in Japan from the age of 5, Grilli, 83, says he has been long enamored by the artistry of traditional Japanese houses, the impressive size of their columns and beams, and their “handmade, craftsman quality,” and has been dreaming of bringing one to the United States for decades. “My whole professional life has been focused on U.S.-Japan cultural exchange. It’s in that context that I began thinking about bringing one to America,” he says.

]]>

An excerpt from the feature-length film, Minka: The Journey of a Japanese Farmhouse. Video © Miho Belmont International

Despite their aesthetic traits, there are an abundance of empty minka in Japan, due to demographic changes, including a declining, aging population and shrinking rural areas. According to an often-cited decade-old report by the Development Bank of Japan, there are more than 210,000 abandoned traditional houses across the country.

Pocket doors allow part of the curved-ceiling connector to open to the surroundings. Photo © Matt Delphenich

Grilli is now executive director of Miho Belmont International (MBI), a private nonprofit formed to acquire a minka and then transport it, re-erect it, and manage it. (MBI plans to use the building to invite small groups interested in Japanese culture for such activities as tea ceremony, ikebana, cooking classes, and dance and musical performances.) The endeavor has been funded by Shinji Shumeikai, a spiritual organization established in 1970 offering a modern variation of Shintoism, with core tenets that include a belief that art and beauty can heal the soul. Internationally, the most well-known architectural manifestation of this philosophy is I.M. Pei’s Miho Museum (1997), in Shigaraki, Japan, which was built to showcase the art collection of Mihoko Koyama, Shinji Shumeikai’s founder.

Stepping inside the Belmont minka today, one can readily understand Grilli’s fascination. Peering into the dimly lit interior from the entry vestibule, one immediately sees the building’s muscular beams, which retain the irregular curves of the ancient trees from which they were hewn. They dramatically interlace over the house’s primary space, or doma, once used for utilitarian activities such as food preparation. It is surrounded by raised floor areas covered in tatami or wood and defined by sliding fusuma and shoji, which open to reveal views of the surroundings, including a newly created traditional-style Japanese rock garden.

Shoji and windows open to a rock garden. Photo © Matt Delphenich

MBI bought the four-acre Belmont property in 2015 for the purpose of erecting a minka. Soon after, a professional farmer and practitioner of Shinji Shumeikai’s version of regenerative agriculture moved into the colonial-style house with his family. He serves as caretaker and cultivates a quarter-acre vegetable garden. It was several more years before MBI identified a minka to acquire, eventually finding it in Shiga Prefecture in a village near Lake Biwa. The house had recently suffered damage in a typhoon—particularly to its roof, clad primarily in thatch, with a lower skirt of ceramic tiles—and the family of rice farmers who had owned it for generations faced the difficult choice between costly repairs and its replacement with a new, modern house. They ultimately decided on the latter. Architect Ryoichi Kinoshita, principal of Atelier Ryo, a Kyoto-based firm that has undertaken more than 40 minka relocations, mostly within Japan, had been aware of the farmhouse, suggesting it would be well suited to MBI’s needs, according to Grilli. Its atypical off-center daikoku bashira (or main column), under the frame’s primary interlacing beams, would allow a generous open space for gatherings.

Before its acquisition, the minka was damaged in a typhoon. Photo © Atelier Ryo

What followed was a period of intense collaboration among Atelier Ryo, Boston-area I-Kanda Architects, Shiga Prefecture–based carpenters Enishi-Giken, and many others. The team painstakingly documented the timber structure and finishes before deconstructing the minka. In a Kyoto warehouse, the carpenters then repaired and reassembled its components before once again taking them apart for transport. The pieces arrived in Belmont in eight shipping containers in October 2023, followed by a team from Enishi-Giken, who, with the aid of a translator, worked with local general contractor Thoughtforms to rebuild the house.

1

2

The farmhouse was reconstructed in a Kyoto warehouse (1) before being shipped in pieces to Belmont and reerected there (2). Photos © Atelier Ryo (1); I-Kanda Architects (2)

In the minka’s recent incarnation, significant (though sympathetic) changes have been made for code compliance, for practicality, and for the comfort of users. The most obvious adaptation is the replacement of the thatch roof with one of red cedar shingles. The new roof’s pillowed edges recall the soft profile of the thatch, and should silver over time, much like the original rice straw, points out Isamu Kanda, I-Kanda principal.

Other modifications are equally consequential but less apparent, including those made to satisfy local seismic requirements. Minka were designed to sway and flex to absorb the energy of earthquakes, while contemporary U.S. codes mandate more rigidity, explains Kanda. For instance, though all the primary structural elements are original, made from a variety of wood species—including cedar, cypress, pine, and zelkova—and still connected with traditional Japanese joinery, the frame now incorporates shear walls hidden within some partitions. In addition, its columns and their stone bases, which previously sat directly on the earth, are now anchored to a concrete foundation.

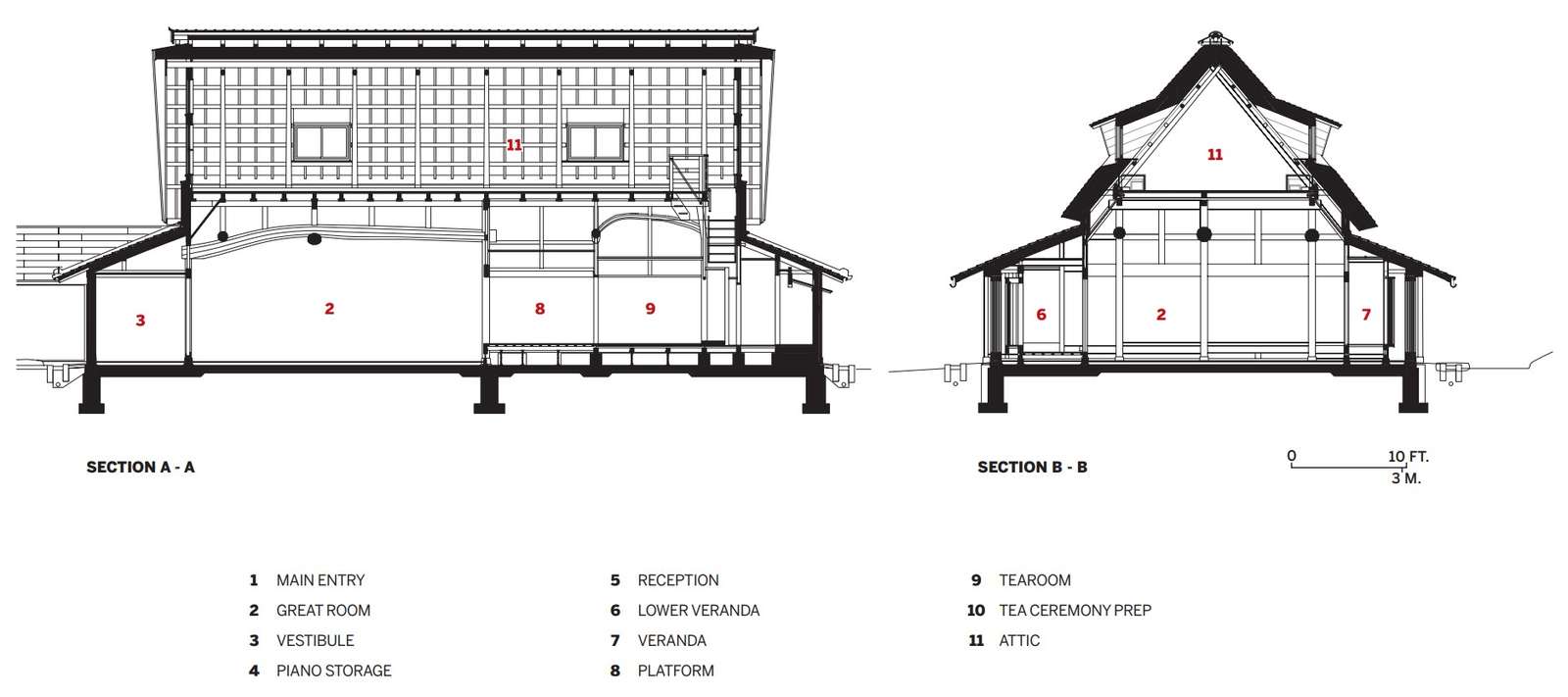

The building’s envelope, too, has been modified to make it less permeable by the elements, with such features as high-performance windows and an extra-insulated roof assembly. Advanced mechanical systems, including an energy-recovery ventilator and humidification controls, are concealed between a dropped ceiling of original bamboo rods and the attic floor.

Due in part to zoning restrictions, the minka was erected as an addition rather than a stand-alone structure. But Kanda has cleverly designed the 45-foot-long passage between the minka and the colonial residence to be more than a physical connection: under an arched Douglas fir ceiling, whose shape was inspired by the historic building’s undulant beams, it contains such functional spaces as bathrooms and a demonstration kitchen. It also provides an ADA-compliant entrance and helps negotiate the elevation differences between the floors of the two houses.

The connector also includes a kitchen, where the client plans to hold cooking demonstrations. Photo © Matt Delphenich

The minka’s many sensitively executed updates make it more than a museum piece. The arduous effort of adapting and transplanting it ensure that it will be used and enjoyed in its new American setting and serve as a compelling illustration of traditional craft, aesthetics, and building techniques—or as Grilli says, “an eloquent, three-dimensional lesson in Japanese culture.”

Image courtesy Atelier Ryo

Image courtesy Atelier Ryo

Credits

Architects:

Atelier Ryo — Ryoichi Kinoshita principal; Kozo Ikeda, Yumi Miki

I-Kanda Architects — Isamu Kanda, principal; Sang Chun

Consultants:

Enishi-Giken (timber frame and finish carpentry); Fire Tower Engineered Timber (structural); Coneco Engineers & Scientists (civil); TE2 Engineering (mechanical); Pro AV Systems (AV); Grayscale Design (FF&E)

General Contractor:

Thoughtforms

Client:

Miho Belmont International

Size:

2,500 square feet (minka); 800 square feet (connector)

Cost:

Withheld

Completion:

May 2025

Sources

Rainscreen:

Nakamoto Forestry

Windows:

Hirschmann

Plumbing Fixtures:

TOTO, Kohler, Rohl

Lighting:

Tech Lighting, Nora, Juno

Lighting Controls:

Lutron